Advertisement

Don't look up? Look down. Geothermal could help curb climate change

They say when you’re in a hole, stop digging. But according to the Environmental Protection Agency, digging deep holes, or more accurately drilling them, is the most energy efficient, cost effective way to heat and cool buildings with no climate disrupting carbon emissions.

The process taps into geothermal, or "ground source," energy which can be used to both heat and cool buildings. The technology has been around for 70 years, and now, an increasing number of Massachusetts communities are putting it to work, including Cambridge.

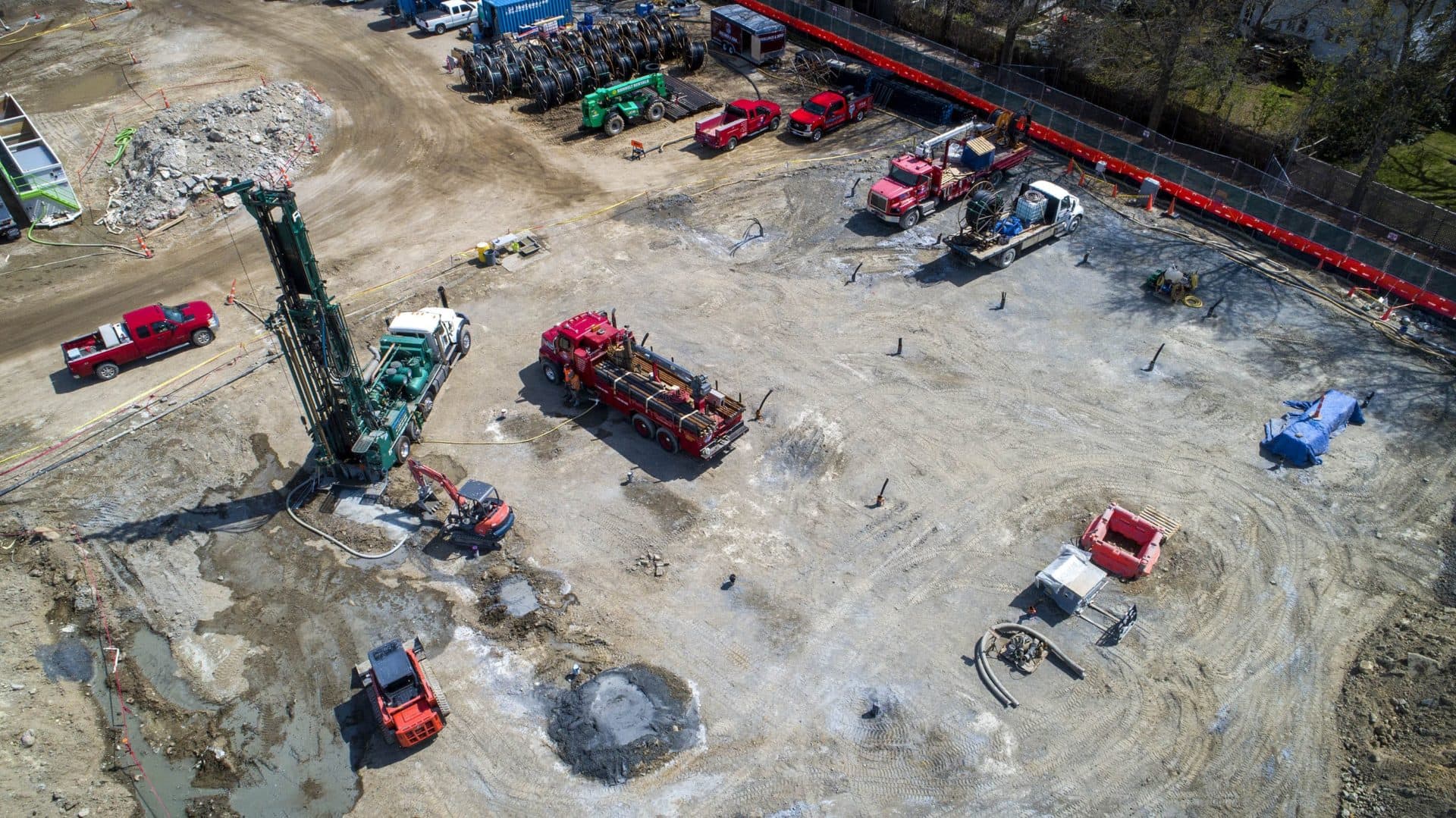

Standing at a nine-acre site near Fresh Pond that will soon be home to two new Cambridge schools, Davida Flynn took in the surroundings.

"It’s incredible what the city of Cambridge is doing here," said Flynn, senior project manager with W.T. Rich Company, the firm is overseeing the construction. "It’s incredible. There’s absolutely no natural gas to this property when this is done. No fossil fuels whatsoever."

When finished, the 360,000 square feet of school space will be heated and cooled without burning a single molecule of fossil fuel thanks to the 75 geothermal energy holes workers are drilling in a distant corner of the construction site.

The open field has plenty of space for the huge drilling machine needed for the work. How big is it? Try 36 feet tall, 35 tons and powered by a 600-horsepower motor.

Roger Skillings, co-owner of the drilling company Skillings and Sons, watches as the drill's tungsten carbide drill bit chews through 500 feet of clay, boulders and tough New England bedrock. If workers hit water it has to be trucked away and treated.

Drilling the 6-inch diameter holes is the most costly part of installing geothermal energy.

"Drilling holes in the ground is expensive," Skilling says. "One of those rigs costs $950,000 — a million bucks."

When completed, the system will draw thermal energy from the earth, where the temperature is a constant 50-60 degrees Fahrenheit, to the surface. Four thin plastic pipes are inserted into each hole, filled with water and antifreeze, and attached to pumps that circulate the liquid through a heat exchanger that keep the buildings comfortable year round.

"That's what's nice about geothermal," Skillings said, "you can cool or heat."

Compared with burning fossil fuels in a furnace, which is typically 75% to 90% efficient, geothermal is 300% to 400% efficient. For each unit of energy needed to operate the pumps, three to four units of thermal energy are extracted.

Photovoltaic panels on the school roofs will provide the electricity needed to power the geothermal system. Skillings calls it a fossil-free match made in heaven and earth.

"Because you’re using an electric heat pump, solar works very, very well," he said. "They marry well together."

The city's construction program manager, Brendon Roy, expects the new system will pay for itself in less than a decade.

"We obviously look at the dollar value," he said. But Roy thinks clean tech has a social bottom line as well.

"Having geothermal means less fossil fuels being used on site and what that means to us is that it’s a payback on the mental health, the physical health of the community," he said. "And so it’s something we really value, and the city is really passionate about, so geothermal has been a fundamental piece of all our project going forward."

Advertisement

Geothermal projects are going forward across the Commonwealth.

Boston University’s new Data Science Center has 31 geothermal holes, each 1,500 feet deep. And just down the block from the Cambridge construction site is Belmont's new middle and high school. The just-finished 450,000 square-foot school is the largest geothermal building in the state. The ground source heat pump system is expected to save millions in energy costs and cut total climate emissions from town buildings by 40%.

"Having geothermal means less fossil fuels being used on site and what that means to us is that it’s a payback on the mental health, the physical health of the community."

Brendon Roy

The over the last 70 years, geothermal systems have proven to be are simple and inexpensive to operate and maintain.

And yet, even with a generous federal tax credit and state incentives, the technology can be a tough sale, especially retrofitting an existing home in a densely populated residential neighborhood, Skillings said.

"It doesn’t work everywhere, " he said. "Natural gas is a big competitor. The economics of natural gas is less expensive for (many) people."

Even Skillings says he's not switching to geothermal in the home he recently moved into. He doesn't want to install costly vents. "To change this house from the forced hot water system to a forced hot air system is very expensive, very expensive."

Energy economist Jurgen Weiss is willing to give home geothermal a try. Weiss lives just off of Mass. Ave. near Porter Square, in a home built in 1895 and has the fossil fuel-burning systems you'd expect in a house that old.

"You know, retrofitting an existing home is not easy."

Not even for someone like Weiss, who has a PhD in economics and specializes in energy transition. He helped Rhode Island design a road map to meet the state’s climate goals and taught energy economics at Harvard Business School.

"Since I work on climate change and energy transition issues I am aware of the fact that I still burn a bunch of fossil fuel," he said. "So I began thinking about ways to get rid of my fossil fuel use."

When he converted his third-floor attic into a master bedroom and bath, Weiss tried installing electric air source heat pumps. They mounted in the walls, took air from the outside and converted it to the desired temperature inside. There were no unsightly air ducts but on the coldest days they didn't work very well and kept breaking down.

"And at that point I started thinking, do I want to keep replacing expensive parts or is there a better solution to this whole thing," he said.

At the time, Weiss was writing a Harvard Business School case study about a start-up called Dandelion Energy. The upstate New York company has big plans to transform home heating by scaling up the use of ground source, geothermal energy.

"One of the things that Dandelion does, they modified an app that exists," Weiss said. "So when I wrote the case study I got this app and installed it."

It instructed Weiss to take a bunch of pictures of his home, "and the app basically constructed a 3D model of my house … in 10 minutes or so."

Dandelion's app and proprietary data of the earth profiling composition, density and thermal conductivity, determined how many geothermal wells Weiss's home would require and how deep to drill.

The company virtually designed a geothermal system for Weiss without ever stepping foot on his property. But there was one big problem.

"There’s not a lot of space to drill holes," Weiss said.

Weiss’s front yard was way too small for the beefy drills being used at Fresh Pond. The back yard was barely more promising.

The only way I could get [the drill rig] here is by ripping out my apple trees and tearing down the fence, and both of those are not great," he said.

Kathy Hannun, co-founder and president of Dandelion Energy, said Weiss' space issue is a common one in dense places like Somerville.

But Sweden, she said, may offer a solution. There, they use small rigs — just 6 feet high — to drill in tight spaces. The rigs use sound waves to help dig the deep holes.

Today, 20% percent of the buildings in Sweden use ground source geothermal for heating and air conditioning.

"By adopting these miniaturized clean technologies we’re making it possible for homes to do geothermal that really could not have done it before," Hannun said.

The company recently began doing business in Vermont and is expanding into Massachusetts and beyond, despite initial sticker shock by homeowners. According to Hannun, the average price for a home geothermal system is about $40,000.

"But there are a ton of incentives available to homeowners right now, which helps bring the price down," she quickly added.

Turns out for Weiss to get geothermal for his Somerville home, the easiest and cheapest solution would be to drill the hole in the middle of the street, in front of his house. Perhaps even better: hook up other homes in the neighborhood to a shared network of deep holes in the street so everyone in the neighborhood can get fossil-free geothermal.

That’s precisely what Eversource is doing this summer at an experimental site in Framingham, and National Grid plans to do, with two pilot programs, next year.

Correction: An earlier version of this story misspelled Kathy Hannun's surname. The story has been updated. We regret the error.

This segment aired on June 30, 2022.