Advertisement

Xylazine, an animal tranquilizer, compounds overdose crisis

Approaching a van that distributes safe supplies for drug use in Greenfield, a man named Kyle noticed an alert about xylazine.

“Xylazine?” he asked, sounding out the unfamiliar word. “Tell me more.”

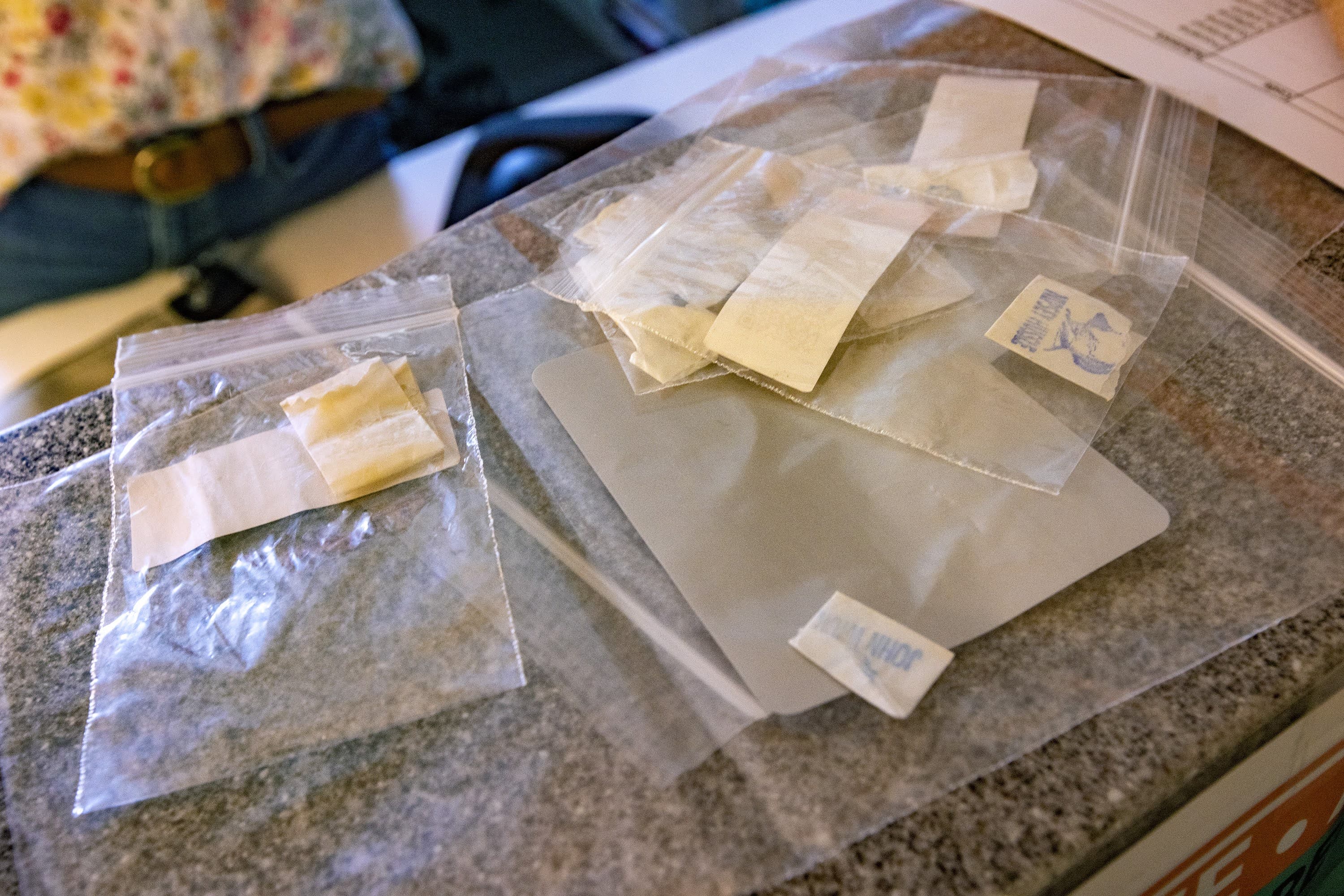

A street outreach team from Tapestry Health delivered what’s becoming a routine warning; xylazine is an animal tranquilizer. It’s not approved for humans, but it’s shown up in about half of the drug samples Tapestry tests — mostly fentanyl, but also cocaine.

Kyle rocked backwards on his heels at the mention of cocaine.

“The past week, we’ve all been just racking our brains, like what is going on,” he said. “We’ve been accusing people of messing with our stuff. There’s been a lot of drama.”

Kyle and his friends thought they were using cocaine. But there was something else in the bag.

“Because if we cook it up and we smoke it, we’re falling asleep after,” Kyle said. WBUR is using first names in this story for people who use illegal drugs.

Kyle’s deep sleep might have been triggered by fentanyl, which is sometimes in cocaine too. But Kyle said one of his buddies used a test strip to check for the opioid and it didn’t show any.

This month xylazine was in a quarter of drug samples tested by the Massachusetts Drug Supply Data Stream (MADDS). It’s a state-funded network of community drug checking and advisory groups that uses spectrometers to let people who use drugs and researchers know what’s in bags or pills purchased on the street.

In some areas of state, including western Massachusetts, researchers found xylazine in 50%-75% of samples. In Greenfield, that’s a big change from last year, when xylazine wasn’t a concern.

Advertisement

“We’ve seen an exponential increase during the pandemic,” said Traci Green, who directs the opioid policy research collaborative at Brandeis and oversees MADDS. “Now the sad thing is we’re really seeing it all over the state. It’s definitely hazardous.”

There’s a lot of speculation about how and why xylazine is on the rise. It may be added to fentanyl or heroin to help extend the effects of an opioid high. Dealers may be using this relatively inexpensive and easy-to-order sedative if there are supply chain gaps with other drugs.

Whatever its path into the drug supply, the presence of xylazine has triggered warnings in Massachusetts and beyond.

As Xylazine Rises, Overdoses Rise Too

Perhaps the biggest concern is xylazine's association with more overdoses and deaths. Researchers in one study found that xylazine was detected in less than 1% of overdose deaths in 2015. By 2020, however, that share increased to 6.7%. The U.S. set a new record for overdose deaths that year. In 2021, fatal overdoses rose again, killing 107,000 people.

The study does not claim xylazine is causing more fatal ODs, but study co-author Chelsea Shover said it may contribute. Xylazine, a sedative, slows breathing, blood pressure and a person’s heart rate, compounding some effects of an opioid like fentanyl or heroin.

“If you have an opioid and a sedative, those two things are going to have stronger effects together,” said Shover, an epidemiologist at UCLA School of Medicine.

In Greenfield, Tapestry Health has responded to more overdoses as more tests show the presence of xylazine.

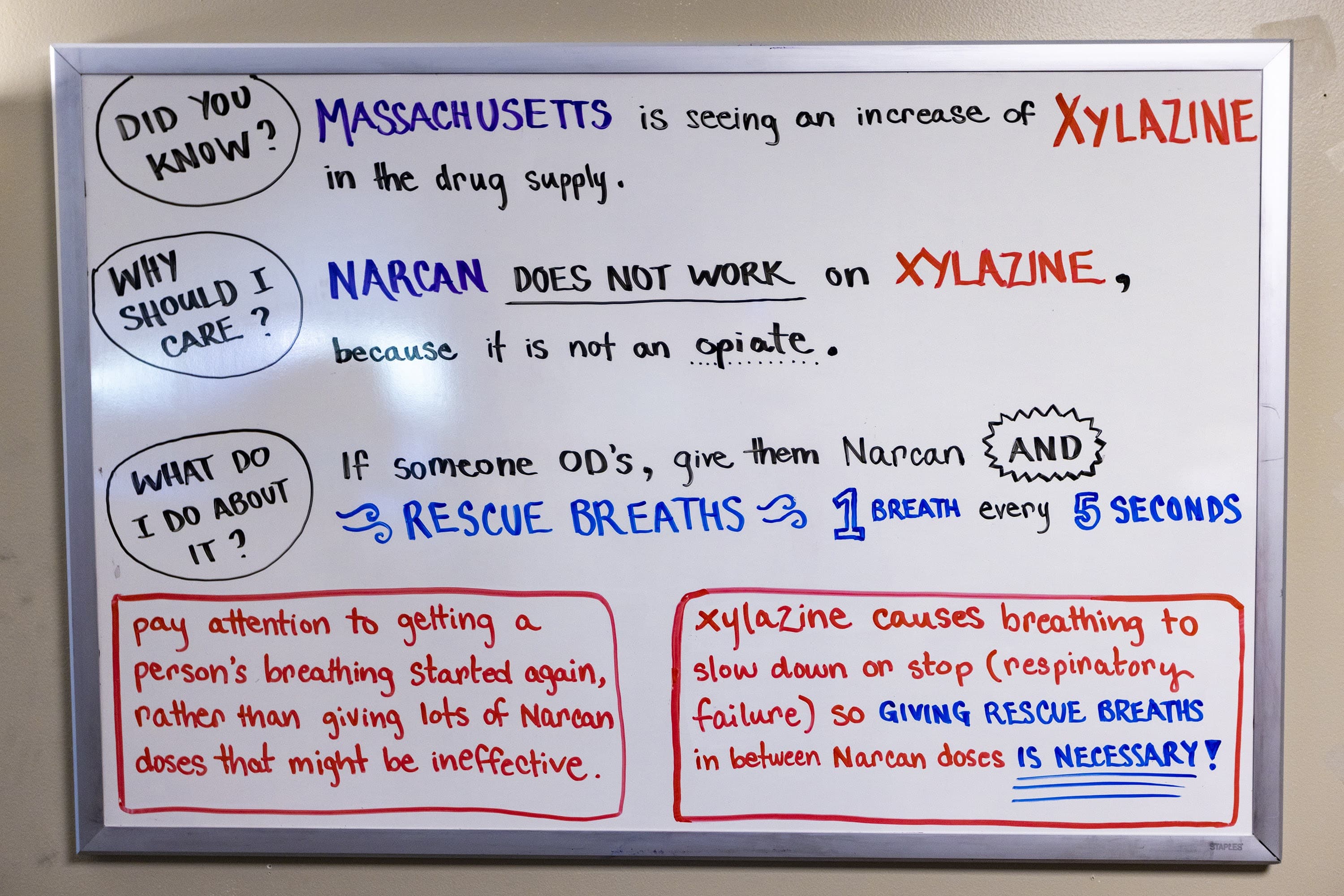

“It correlates with the rise, and it correlates with Narcan not being effective to reverse xylazine, said Amy Davis, the assistant director for rural harm reduction operations at Tapestry.

“It’s scary to hear that there’s something new going around that could be stronger maybe than what I’ve had,” said May, a woman who stopped by Tapestry’s van. May said she has a strong tolerance for fentanyl, but a few months ago, she started getting something that didn’t feel like fentanyl, something that “knocked me out before I could even put my stuff away.”

A Shifting Overdose Response

Davis and colleagues are ramping up the safety messages: Never use alone, always start with a small dose and always carry naloxone, also known by the brand name Narcan.

They've also changed the way they talk about drug overdoses. Staffers begin by explaining that xylazine is not an opioid. Squirting naloxone into someone’s nose won’t reverse a deep xylazine sedation.

With xylazine, the immediate goal is to make sure the person is getting oxygen into their brain. So Davis and others advise starting rescue breathing after giving the first dose of Narcan. It may help restart the lungs even if the person doesn’t wake up.

“We don’t want to be focused on consciousness, we want to be focused on breathing,” Davis said.

Giving Narcan is still critical because xylazine is often mixed with fentanyl, and fentanyl is killing people.

“If you see anyone who you suspect has an overdose, please give Narcan,” said Dr. Bill Soares, an emergency room physician and the director of harm reduction services at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield.

Soares said calling 911 is also critical, especially with xylazine, “because if the person does not wake up as expected, they’re going to need more advanced care.”

‘Profound Sedation’ Worries Health Providers

Some people who use drugs say xylazine knocks them out for six or eight hours, raising concerns about the potential for serious injury during this “profound sedation,” said Dr. Laura Kehoe, medical director at the Massachusetts General Hospital Bridge Clinic.

Kehoe and other clinicians worry about patients who get xylazine and go out while lying in the sun or snow, in one position, perhaps in an isolated area.

“We’re seeing people who’ve been sexually assaulted,” Kehoe said. “They’ll wake up and find that their pants are down or their clothes are missing, and they are completely unaware of what happened.”

Kehoe said the surge of xylazine heightens the need for supervised consumption clinics, where people can use drugs under the watch of trained staff. Legislation that would allow a pilot program in Massachusetts is still in committee at the State House, with just a couple of weeks left in this year’s formal sessions.

Newton Police Chief John Carmichael, who chairs the Massachusetts Chiefs of Police Association’s substance abuse committee, is opposed to the pilot program. Carmichael said in his experience, people who buy illegal drugs use them immediately and wouldn’t take the time to travel to one of these sites.

“So I just don’t see how these sites would be really effective,” Carmichael said. “And I find it to be a little immoral as well that somebody who I think we should really be trying to help, getting them into treatment and recovery, and I think we have an obligation to do that more so.”

A study conducted in Vancouver showed an increase in treatment as the city added overdose prevention sites.

Another study out of France last month found that people who use supervised consumption clinics have fewer boils and abscesses related to injections. Clinicians say that’s especially compelling now, with xylazine.

In Greenfield, nurse Katy Robbins pulled up a photo from a patient seen in April as xylazine contamination soared.

“We did sort of go, ‘Whoa, what is that?’ ” Robbins remembered, studying her phone.

The image shows a wound like deep road rash, with an exposed tendon and a spreading infection. Robbins and Tapestry have created networks so clients can get same day appointments with a local doctor or hospital to treat this type of injury.

“They can, and they won’t because there’s so much stigma and shame around wounds from injection drug use,” said Robbins. “Often people wait until they have a life-threatening infection.”

That may be one reason why amputations are on the rise among people who use drugs in Philadelphia, where xylazine has surged. The sedative is now in more than 90% of samples there.

“We’re certainly seeing a lot more wounds, and we’re seeing some severe wounds,” said Dr. Joseph D’Orazio, the director of medical toxicology and addiction medicine at Temple University Hospital in Philadelphia. “Almost everybody is linking this to xylazine.”

D’Orazio and his colleagues are still trying to figure out why wounds are worse with xylazine use. It could be that wounds don’t heal as quickly because xylazine reduces blood flow. Some patients also report more skin picking with xylazine. There’s a lot clinicians still don’t know about the effects of this drug that has not been approved for use in humans.

D’Orazio said xylazine withdrawal is also challenging because it is accompanied by extreme anxiety. One patient described the feeling of being trapped in a room that’s on fire. This level of anxiety makes it more difficult to speak with people about treatment and get them into detox programs.

“It’s not like other sedatives that we have experience with,” said D’Orazio.

This segment aired on July 15, 2022.