Advertisement

Separating green hydrogen's hope from hype

Nearly 150 years ago, Jules Verne's novel "Mysterious Island" captured the world's imagination and foretold a future of unlimited, clean energy.

"Yes, my friends, I believe that water will one day be employed as fuel, that hydrogen and oxygen which constitute it, used singly or together, will furnish an inexhaustible source of heat and light, of an intensity of which coal is not capable."

Verne was on to something. Massachusetts scientists and companies are trying to make good on the author's vision and create the supply and demand needed to create a hydrogen fuel market.

To do so, the state has teamed up with New Jersey, New York and Connecticut in a bid to become one of at least four regions designated a "hydrogen hub" by the Department of Energy. The $9.5 billion initiative is designed to dramatically bring down the cost of separating hydrogen from water without the use of fossil fuels, providing a platform to build the clean technology's market.

Hydrogen has a lot going for it. It's the most abundant element in the universe and packs a powerful energy punch. When hydrogen is combined with oxygen in a fuel cell, it produces electricity, and water is the waste product. The electricity can be put to work powering trains, planes and automobiles.

Gallon for gallon, hydrogen carries three times the energy of jet fuel. Refueling takes just minutes, compared to the hours needed to fully recharge lithium-ion batteries used today in most electric vehicles.

To get that hydrogen, scientists use a process called electrolysis, which separates the two hydrogen atoms from the oxygen atom in water. To unlock the energy potential of that liberated hydrogen, its combined again with oxygen, delivering power to whatever device you're using, with water its only byproduct.

"Green hydrogen is the kind we want."

Benjamin Sovacool

Hydrogen is a colorless gas, but scientists use a color-coded system to describe the energy used to split water into hydrogen and oxygen.

"There’s gray and black, which is fossil fuel," said Benjamin Sovacool, director of Boston University's Institute for Global Sustainability. "There’s blue, which comes from natural gas; and there’s green, which comes from renewables; and there’s pink, which comes from nuclear power."

Today, close to 95% of hydrogen produced is "black," using methane, a carbon-emitting fossil fuel. It releases nearly 10 times as much CO2 into the atmosphere as using clean-burning hydrogen saves.

"Green hydrogen is the kind we want," Sovacool said. His book, "Visions of Energy Futures: Imagining and Innovating Low-Carbon Transitions," details the hype and hopes for green hydrogen that have persisted through history in the hearts and minds of scientists and politicians.

But the hype over hydrogen is turning to real hope due to the growing development of fossil-free, renewable energy to drive the purification process.

"Because of advances in renewable energy, because of the advances in electrolysis technologies, it’s absolutely feasible to see that within 10 years that we could have a massive piece of the energy infrastructure based on green hydrogen," said Andy Belt, CEO of Giner Incorporated, a research company based in Newton.

Advertisement

For 50 years, scientists at the independent lab have pioneered much of the breakthrough hydrogen-energy research.

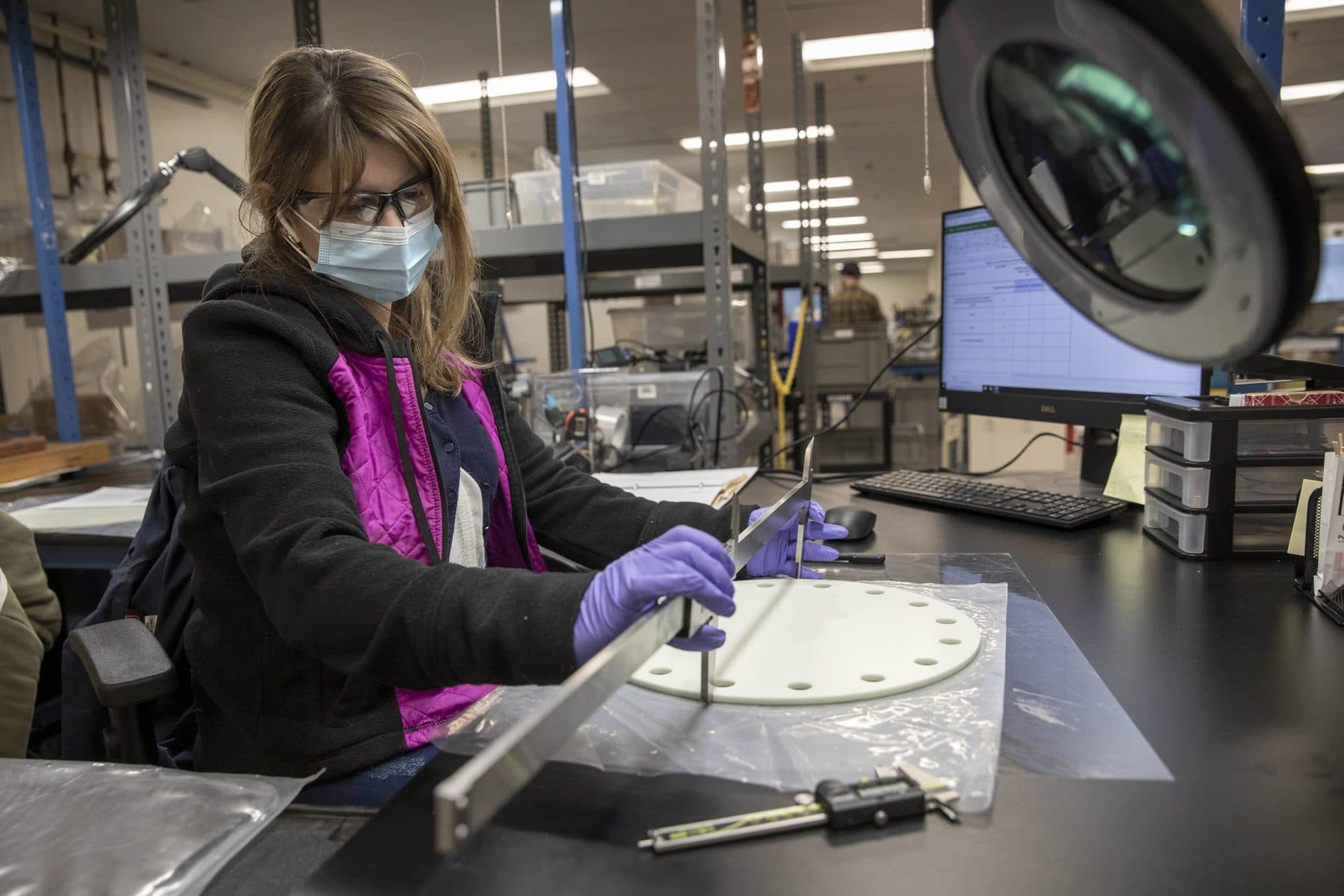

Giner has developed several machines, called electrolysers, to split water molecules.

"In the guts of the electrolyser, where the magic happens, you combine water with electricity and you break the bonds of water and out comes hydrogen and oxygen and that's the magic of an electrolyser,” Belt said.

Inside the devices are thin membranes, coated with precious metals — platinum and iridium. Ironically, isolating the most abundant element in the universe requires two of the rarest substances in the world.

That rarity comes at a cost, complicating the effort to make hydrogen fuel affordable. But the $40,000 worth of metal used in a large electrolyser can be recycled and recovered. And according to Belt, the price of renewable electricity is so cheap that the cost of making a kilo of hydrogen in Giner’s electrolyser “is a buck or less."

That's one of the main goals of the U.S Department of Energy's hydrogen project: cut the cost of producing "green" hydrogen by 80% by the end of the decade, so the energy equivalent of a gallon of gasoline would cost about a dollar.

Belt believes hydrogen will power drones flying high in the sky and autonomous boats deep below the oceans, which could run for months — even years — without refueling. The vehicles would use fuel cells that re-combine hydrogen and oxygen to produce water and electricity. The fuel cell technology was pioneered by General Electric in Lynn in the 1960s and used as the power supply aboard NASA's Gemini space capsule.

Newton-based Giner has big goals, but even bigger hydrogen applications are being planned by another company, about a half-hour away in Concord.

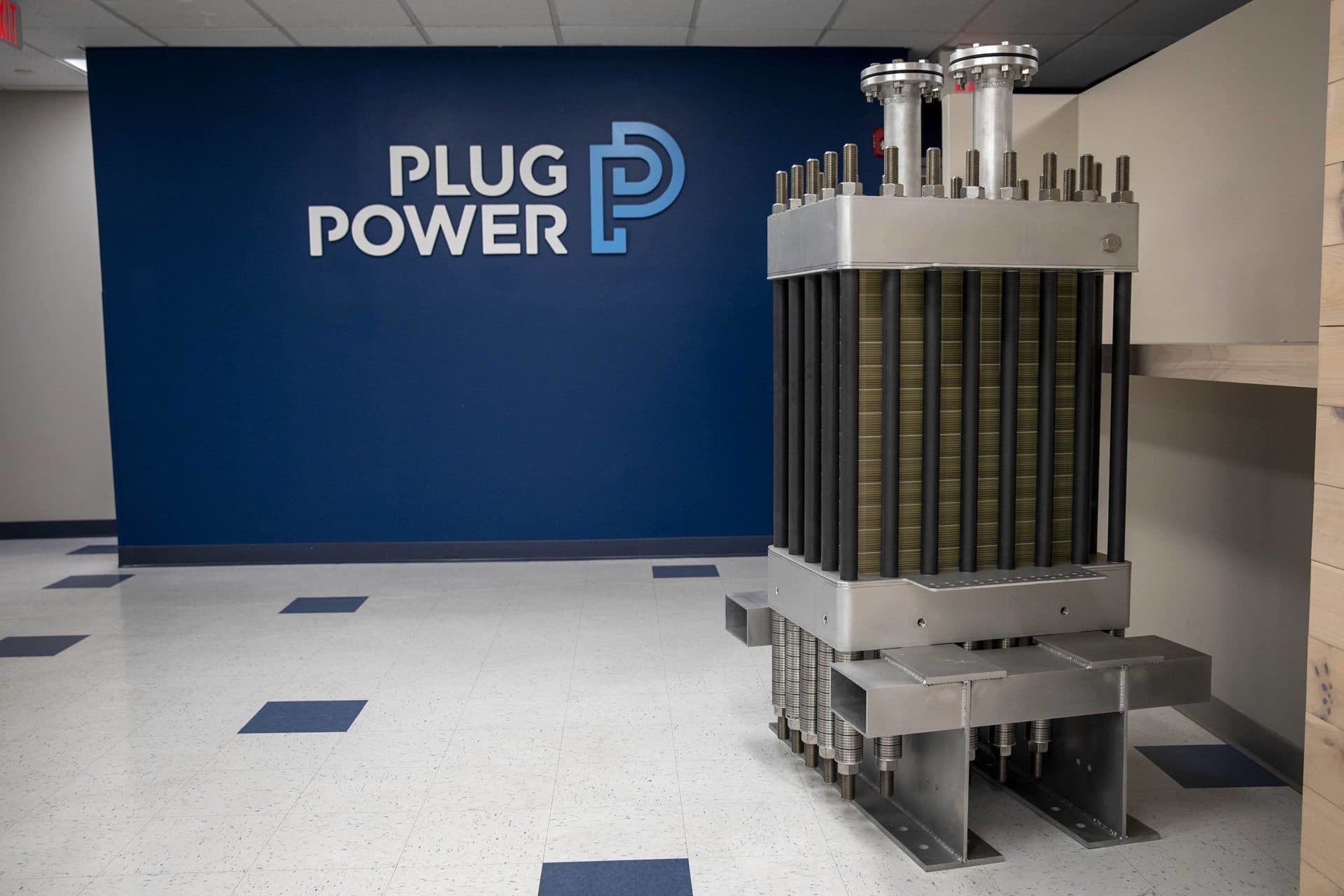

"I like to say we're starting the second revolution here in Concord, Massachusetts," said Corky Mittelsteadt, vice president of Plug Power.

Two years ago, Giner sold its large-scale electrolyser manufacturing business to Plug Power, a New York firm that operates a facility in Concord. The company wants to become the world’s leading producer of green hydrogen by mass-producing large water-splitting electrolysers based on Giner’s technology and bring down costs through economies of scale.

Commercializing industrial-sized electrolysers could revolutionize how companies produce create some of the basic building blocks of our world, from jet fuel to fertilizers, he said.

"In the context of renewable energy, scale is everything," Mittelsteadt said. "We're pushing the technology further and faster than anyone in the world."

Plug Power is building three sizes of electrolysers, each named for a river in New England. The largest — the Allagash — looks like a shiny, squat refrigerator. It weighs 3,700 pounds.

The first seven Allagash electrolysers were delivered to Germany, where the hydrogen produced is used in fuel cells for locomotives. Electricity from wind farms power the electrolosis process, and the hydrogen created is then used in the fuel cells.

The seven devices make three-and-a-half tons of hydrogen a day, equivalent to the energy produced by burning 7,000 gallons of diesel.

The process, which moves energy from wind to hydrogen to fuel cells to the train wheels, is designed to use and produce little or no disrupting emissions.

Plug Power plans to produce 500 similar electrolysers a year. The company expects to double production annually, adding future plants in Georgia, California, Texas and Belgium.

Mittelsteadt predicts that, by 2025, Plug Power’s machines will produce enough hydrogen to generate 5 gigawatt hours of power a year.

That's the energy output of about five large nuclear power plants.

"Far more than all the electrolysis in the world today," he said.

As companies like Giner and Plug Power work to increase the supply of hydrogen in the market, other players are working on demand.

In a double-sized hanger at Minute Man Air Field in Stow, workers from Alakai Technologies assemble prototypes of clean, green flying machines.

"We're building a hexacopter that will fly up to 400 miles," said Alakai Chief Operating Officer Bill Spellane. "We're hydrogen-powered, not battery-powered. We do hydrogen."

Dubbed SKAI, the six-rotored copter looks like a futuristic flying mini-van. SKAI can carry four passengers or 1,000 pounds of cargo and a pilot.

Aboard SKAI will be cylinders of liquid hydrogen kept under pressure at minus 423 degrees Fahrenheit. When combined with oxygen from the air the cells will produce the electricity needed to speed SKAI through the air at 115 mph.

Alakai plans to market SKAI for air taxi and cargo services, medical emergency flights and disaster relief.

"We want to build right here, right in Massachusetts," Spellane said. The company plans to build 400 SKAI aircraft a year.

The same hydrogen fuel cell technology that Alakai plans to use to produce hexacopters could soon be used to ferry passengers in Boston Harbor.

"We're turning hydrogen into electrons and electricity," said Pace Ratti, founder and CEO of Switch Maritime. The Washington state company is conducting open water trials of the 70-foot Sea Change. The hydrogen-powered ferry will soon passengers across San Francisco Bay.

Judith Lattimer, a senior project scientist at Giner, looks to the horizon for ways to make hydrogen cheaply at sea. She’s working on coupling offshore wind farms with electrolyser at sea to produce hydrogen for fueling ships or using a pipeline to bring it ashore.

That’s precisely why Shell oil recently announced it was planning on doing. It’s going to build the world’s largest green hydrogen facility at a wind farm off the coast of Holland. BP and Chevron have also announced multi-billion dollar hydrogen programs. China, Saudi Arabia, European and South American nations have also invested billions into research efforts to make hydrogen the fuel of the future.

Boston University's Sovacool still has doubts about the future of a green hydrogen economy. But he's cautiously hopeful the proposed federal hydrogen hub program could help companies to make it happen.

"They won't happen by themselves in the market," he said, "but if they had the right sort of incentives and policy, I could see it happening."

It's a future Jules Verne predicted in 1875. And while the science is no fiction, achieving that vision depends on making green hydrogen truly green by creating uses that are climate clean and profitable.