Advertisement

9 takeaways from WBUR's investigation into the impact of Mass.' domestic and sexual violence secrecy law

A WBUR investigation found that a sweeping privacy law designed to help victims of sexual assault and domestic abuse has regularly wound up harming them instead.

It has shielded law enforcement departments and officers from scrutiny, thwarted researchers studying ways to reduce violence and blocked victims from obtaining records they need for custody battles and restraining orders.

Here are nine key takeaways from reporting the story:

1. No other state has a confidentiality law so broad

Massachusetts is the only state that keeps hidden from the public all arrests and police reports involving sexual and domestic violence, according to advocates and public records experts.

Other states take narrower approaches to protecting the privacy of victims. Vermont, for instance, permits police to black out the names of victims and witnesses on records. But police cannot normally withhold entire reports in Vermont just because they relate to domestic or sexual violence.

By contrast, Massachusetts law requires police departments to keep the entire report confidential if it involves sexual or domestic violence. The rules also require police to omit arrests and incidents from their public police log if they involve rape, sexual assault or domestic violence. The records are also exempt from the state public records law, making it difficult for journalists, researchers and others to obtain information about such crimes.

2. The law has failed to accomplish its main goal

When the Legislature broadened the privacy law to apply to domestic violence in 2014, supporters argued it was needed to encourage victims to come forward and report crimes to police. (The original 1974 law applied just to cases involving rape and sexual assault.)

But there’s no evidence the law actually prompted more victims to come forward. WBUR collected data from more than a dozen of the largest police departments in the state and found no change in the number of reports of domestic violence.

3. The statute has made it harder for survivors to get access to records

Domestic violence advocates say police now regularly refuse to let victims see their own reports – documents victims often need to obtain restraining orders or fight custody battles.

That’s despite the fact that the law contains a specific exception for victims. In some cases, advocates say police simply aren’t aware of the rule. In other cases, they say, the exception is far too narrow. For instance, police refused to give a domestic assault victim a recording of a 911 call about the incident, because the call was placed by a neighbor – not the victim. And a South Shore mother was turned away when she sought records of her estranged husband abusing other women, because she wasn’t the victim in those other cases.

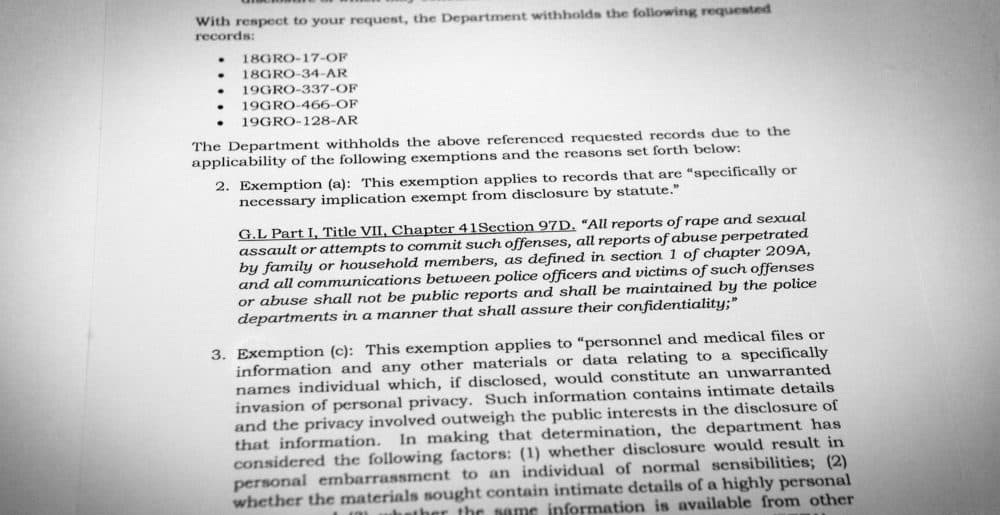

4. Police regularly use the law to withhold information about officers accused of misconduct

WBUR found more than 40 police departments in Massachusetts refused to release information about officers accused of domestic violence, rape, molestation of children or other types of sexual assault. Some wouldn't even provide their names.

In one recent high-profile case, Boston police cited the law to withhold records on Patrick Rose, who remained with the police department for more than two decades after he was first accused of molesting a child. He is now in prison after being convicted of assaulting six children.

But Boston and dozens of other communities across the state rejected WBUR's request for records on other officers accused of misconduct, saying the law requires them to keep the documents confidential.

5. Departments have cited the law to keep unsolved rapes secret

Quincy and Framingham police said they each recorded three reports about unsolved stranger rapes in recent years. But they refused to provide any details of the crimes and neither recalled alerting the public. It's not clear whether the assaults were all committed by different people or serial rapists who are still on the loose.

Transparency advocates say the decision to keep the assaults secret raises questions about whether they put the public at risk or missed crucial opportunities to catch the suspects.

6. The law makes it hard to tell how police handle reports of domestic violence

WBUR found more than a dozen murders in recent years where police acknowledged they had received previous reports of domestic violence involving the same people, but refused to release the records.

Because the reports are secret, it’s hard to examine how police handled those earlier calls for help and whether they could have done more to prevent the killings.

Police say the privacy law requires them to keep the information secret, even though the victims are dead.

7. It’s thwarted researchers and journalists studying domestic violence

Boston Police used the law to withhold response times to domestic violence calls. A Northeastern University professor studying suicides was blocked from obtaining records for people who had been involved in abuse. And another professor said she likely couldn’t include Massachusetts in a national study of domestic violence. Scholars say that could potentially make it harder to find ways to reduce violence or identify problems with the way Massachusetts handles such crimes.

8. Prosecutors say the law has never been enforced

WBUR contacted the offices of all 11 district attorneys and the attorney general’s office in Massachusetts. None of them could cite a single case where they have ever prosecuted police for releasing records under the statute.

Critics say that essentially means police can decide on their own what to release and what to withhold. WBUR found dozens of examples where police decided to release some records or information about domestic violence or sexual assault and were never prosecuted. But the release is often selective. And some advocates worry police could take advantage of the law to release information that makes them look good, such as an arrest of a serial rapist, while withholding records that make them look bad, such as those involving unsolved crimes or public officials accused of wrongdoing.

9. There’s appetite for change

Some of the original sponsors of the law said they would be open to a review of the law’s effectiveness and possible changes.

Jane Doe Inc., the state’s main advocacy organization for domestic and sexual violence survivors, initially supported the law. But after hearing WBUR’s findings, the organization's leaders said it’s time for a study or commission to re-examine the statute.

“While this law was intended to increase survivor safety and protect survivor privacy, there is a very clear, unintended consequence of empowering law enforcement, police departments, to really assert even increased power and control over access to information and records,” said Hema Sarang-Sieminski, policy director at Jane Doe Inc. "I think it's time to address it.”

Grace Ferguson of WBUR contributed to this report