Advertisement

New biography wrestles with Isabella Stewart Gardner's contradicting complexities

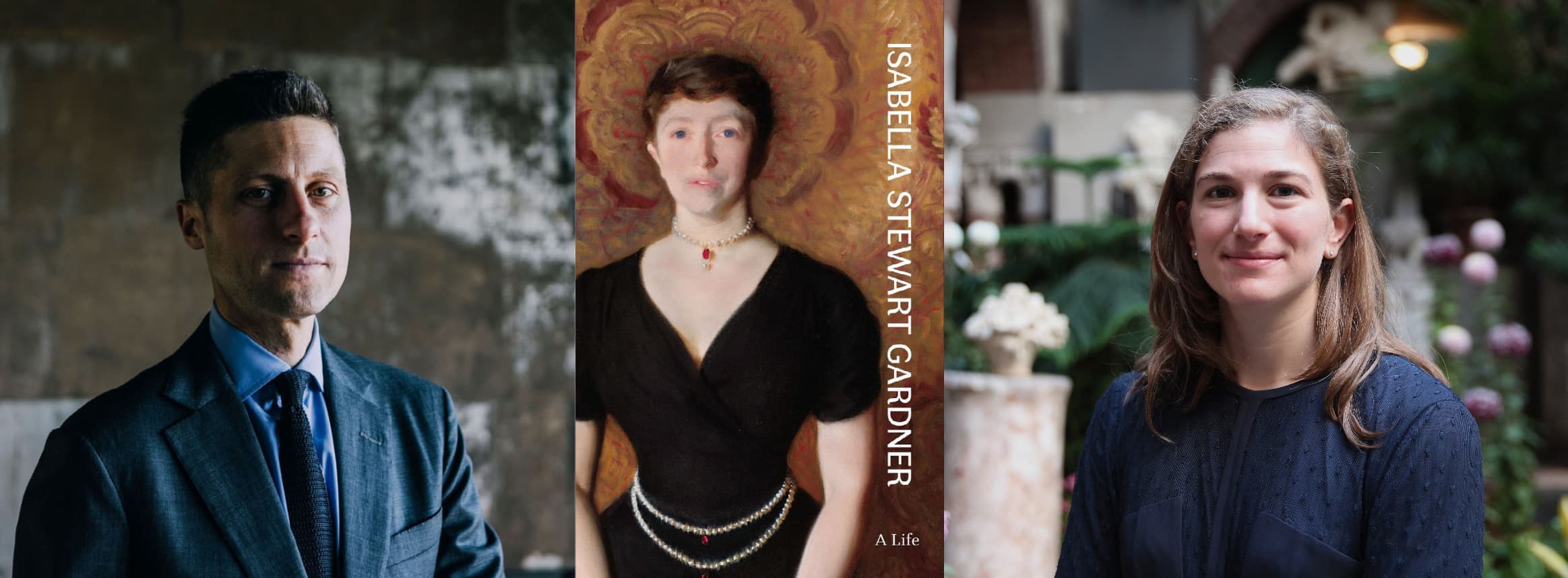

Who was Isabella Stewart Gardner? It’s a question that Diana Seave Greenwald and Nathaniel Silver, curators at the museum that bears her name, have heard from visitors countless times. Even for these experts, it hasn’t always been an easy question to answer. “By design, she made herself a mystery,” says Greenwald.

In their new book, “Isabella Stewart Gardner: A Life” (out Nov. 29), Greenwald and Silver attempt to shed light on this complex woman and cut through the misconceptions that have grown up around her. It’s the first biography of Gardner issued by the museum since Morris Carter’s “Isabella Stewart Gardner and Fenway Court” in 1925.

Silver, who recently left the Gardner Museum to become the executive director of Hancock Shaker Village, saw the book as an opportunity to set the record straight and provide much needed context for Gardner’s life and wealth. “The closer biographers were to Gardner’s time,” says Silver, “the more tempting it was to go to sources who knew her personally. These are very compelling sources, but they’re not unbiased. You’re never quite sure if what you’re getting is truth or fiction.”

In many ways, “Isabella Stewart Gardner: A Life” seems to be an answer to perceived shortcomings in both the Carter biography and Louise Tharp’s 1965 biography, “Mrs. Jack,” which may have offered a somewhat patronizing view of their eccentric subject. For Greenwald and Silver, the task was not a simple one. Gardner left very little personal documentation behind. The museum itself was her legacy, and it was meant to speak for her.

Furthermore, Gardner cultivated a flamboyant public persona that made her the talk of Boston society and a target for scurrilous rumors that have made it hard to separate fact from fiction. In the book, Greenwald and Silver reproduce an illustrated news clipping that shows her walking through the Boston Public Library alongside a tame African lion and relates a story where she shocked the staid audience at Symphony Hall by showing up to a performance wearing a Red Sox hatband. “That Mrs. Jack Gardner should resort to such sensational methods to keep herself before the public eye,” declared a 1912 Town Topics column, “[it] looks as if the woman has gone crazy.”

But there was a method to her madness. “I think that persona helped her achieve a lot of what she did,” says Greenwald. “The eccentricity and the stories were a bit of a distraction that freed her from the expectations of her gender at the time.”

The flip side was that the magnitude of her accomplishments has gone largely unacknowledged in the century following her death, with many writers focusing more on her quirky exploits. “She was the first woman to build a museum in the United States,” says Silver. “Even the way in which she was collecting was pioneering. She was collecting Raphael, Giotto, and Fra Angelico before any other collector in the U.S. In the past, she’s been lumped into a category of collectors but she was the one that did it first and she deserves the credit for that.”

These accomplishments were fueled by her vast wealth. Greenwald and Silver delve into the provenance of Gardner’s money—she inherited a fortune made in linens, textiles, and manufacturing; her husband, Jack, inherited money made through trade in goods from the East Indies. The authors are scrupulous about the implications of 19th-century wealth, noting that while there isn’t hard evidence that Isabella and Jack’s forebearers directly utilized slave labor, they certainly “transacted business with slave regimes and imported commodities produced by enslaved labor.”

“It felt really important to clarify that and place her in that moment,” says Greenwald, “to understand where that privilege and those resources came from and what they enabled.” Silver agrees. “To leave that part out of it would be to ignore a fundamental part of our own socioeconomic history as a country,” he says.

In some ways, the more we learn about Isabella Stewart Gardner, the more complicated a figure she becomes. She was both a trailblazer who bucked against the oppressive sexism of her time and an exemplar of great privilege, whose extreme wealth gave her great power. She ran in bohemian circles and attended gender-bending parties at a queer artist colony in Gloucester, Massachusetts, but never shed her patrician prerogatives and had little to say about the great social causes of her time, including women’s suffrage.

“She is someone to be admired in terms of her willingness to be out in front and bust norms,” says Greenwald. “But that doesn’t mean she’s a perfect person.” Silver hopes that the book will compel readers to wrestle with Gardner’s contradicting complexities. “This biography isn’t an endpoint,” says Silver. “If we are successful in what we did we will have helped to open up new questions that people will continue to pursue.”