Advertisement

Study taps pharmacies as addiction treatment option during opioid crisis

There are medications that help people addicted to opioids stop using these powerful drugs and avoid a potentially deadly overdose. But fewer than 15% of patients who could benefit receive them.

Researchers in Rhode Island tested one possible remedy. They created an addiction care program in six pharmacies.

Results from the study, published Wednesday in the New England Journal of Medicine, show patients were 72% more likely to continue treatment for a month at a pharmacy than patients who received the same care in a more typical outpatient program. The risk of an overdose or an emergency room visit for other reasons were roughly the same for patients in both settings.

The study’s lead author, Traci Green, co-directs the Center for Biological Research Excellence on Opioids and Overdose at Rhode Island Hospital. She said the study shows pharmacies are a safe and effective way to expand addiction treatment.

“We need a lot more [options] if we’re going to try to turn the tide in the opioid crisis,” said Green. “And pharmacists are at the ready.”

Mike, a longtime heroin user, said the buprenorphine (brand name Suboxone) he received through the study saved his life. Mike was waiting for a bus when he saw an ad for participants. He was in recovery at the time, on buprenorphine, but someone had stolen his supply.

“I was very gloomy, I didn’t know what I was going to do,” he said. “I didn’t want to go back on drugs. I just happened to see the sign. It was a godsend.”

At the Genoa pharmacy in Providence, Mike got a new prescription and resumed treatment right away. Without that quick access to buprenorphine, Mike said he would likely have relapsed.

“The alternative would have been fentanyl, which is a crapshoot,” he said. “I’ve seen too many people die.”

We’re only using Mike’s first name to avoid the housing and job discrimination many former drug users face. Addiction experts say that stigma could be a major barrier to expanding this pilot.

Advertisement

“It’s everywhere, everywhere” said Dr. Margaret Jarvis, chief of addiction medicine at Geisinger Health System in Pennsylvania. “There’s not a place in our society, especially within the health care industry, where that doesn’t exist.”

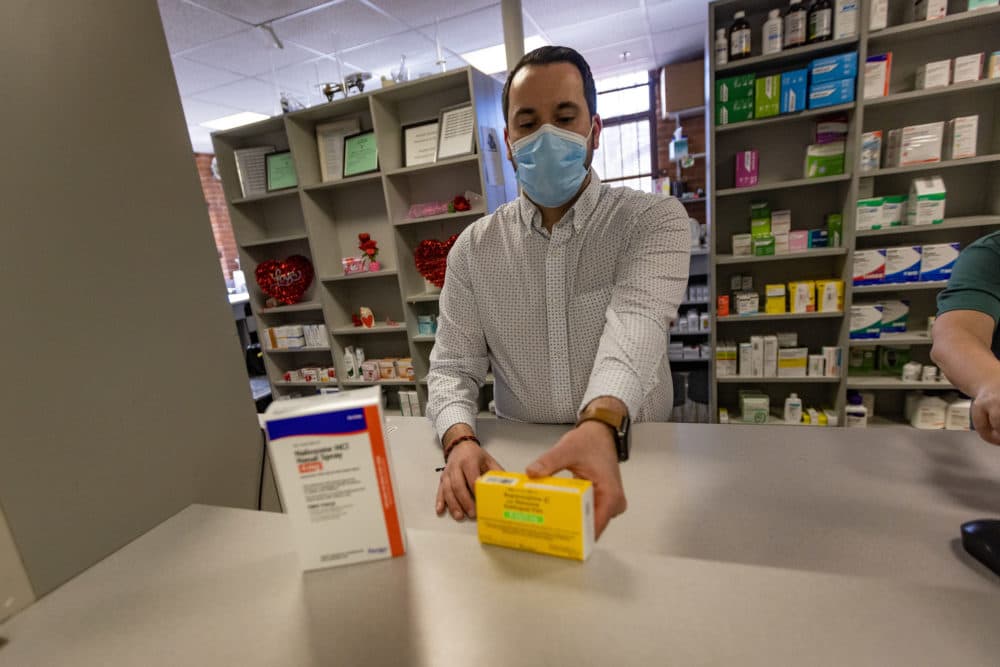

Researchers in the study partnered with Genoa Healthcare, a national chain that runs pharmacies inside or near community behavioral health centers. Andrew Terranova, who manages a pharmacy in Providence that participated in the study, said Genoa pharmacists are used to working with this population of patients.

“I can’t speak for other pharmacists,” said Terranova, “but for my team, we did not see stigma as a barrier."

Researchers trained 21 pharmacists at six Rhode Island locations in areas with high rates of drug overdose. Study participants could walk in or make an appointment to start one of two medications: buprenorphine or naltrexone. All requested buprenorphine, a low-potency opioid that helps patients manage cravings for something stronger.

Walk-in addiction treatment clinics are unusual in the U.S. Jef Bratberg, a co-investigator on the study, said the pilot offered treatment on demand to Rhode Islanders for the first time.

“Instead of calling a clinic, saying I’d really like treatment, and they say, ‘It’ll be weeks,’ even in the best circumstance, an outreach worker, as part of the study could say, ‘Are you interested in treatment today?’ and they’d get treatment that day,” said Bratberg, a professor at the University of Rhode Island College of Pharmacy.

During the first visit, Genoa pharmacists spent an hour, on average, getting to know the participant, taking notes on their medical and drug histories, and assessing their state of withdrawal. Then the pharmacist called a nurse or doctor.

Pharmacists in Rhode Island can't prescribe buprenorphine. But the state allows them to manage care for patients with a doctor’s prescription through a collaborative practice agreement. Pharmacists in 10 states may soon be able to administer buprenorphine on their own because of a new federal law that lifts restrictions on the drug.

One hundred study participants had that first conversation with a pharmacist. A fairly large portion, 42, didn’t continue. It’s unclear why. The researchers suspect some factors may include that 44% of study participants did not have stable housing, and 80% were unemployed. Managing an illness is especially challenging for people who don’t have reliable shelter or food.

And here’s another factor that might have affected return rates: Fentanyl is making it harder for patients to transition to buprenorphine because the withdrawal symptoms last longer and are more difficult to manage.

The remaining 58 participants who chose to continue treatment were divided into two groups. One continued visits, often weekly, to the pharmacy. The other patients were enrolled in a more typical outpatient addiction treatment program. Of that second group, 19 people refused to stop using the pharmacy and are a key reason the pharmacy care continuation rates were much better than the usual care.

Green said many study participants preferred the pharmacy because going there felt familiar and wasn’t embarrassing. There were no armed guards as there are at some treatment sites. People could bring their children with them for appointments. And no one was kicked out if a saliva test showed traces of other drugs.

The study unfolded as the U.S. set a new record of more than 110,000 suspected deaths after a drug overdose. The National Association of Chain Drug Stores said community pharmacies are an untapped resource that should be used to help patients addicted to opioids.

“Implementing more pharmacy-based medications for opioid use disorder support programs — similar to what was stood up in Rhode Island — would allow more clinicians to expand access to essential treatment services for their patients in need,” said the group's spokeswoman, Kathleen Bashur, in an email.

But besides stigma, there are other reasons addiction care isn’t available, and hasn’t been tried, at neighborhood pharmacies beyond a couple of pilots and some limited programs. Dr. Jarvis, at Geisinger Health System, said some physicians may have concerns about delegating authority to pharmacists, relinquishing control of a patient’s care and about the loss of payments tied to visits. Pharmacies in most states report staffing shortages. And there’s another dilemma.

Insurance companies, Medicare and Medicaid don’t see pharmacists as medical providers, so they can’t bill for patient care.

“So to mainstream this in a significant way, there would have to be a payment model to support the pharmacist’s time with the patient,” said Anne Burns, vice president for professional affairs at the American Pharmacists Association. “It’s not impossible, and we think it has merit.”

Law enforcement officials are sometimes apprehensive about expanding access to buprenorphine because it, like other prescribed drugs, can be diverted, or traded on the streets. In Rhode Island, possession of buprenorphine is decriminalized, and Green said many study participants had previously tried using someone else’s buprenorphine. If anything, she argues, the study reduced diversion.

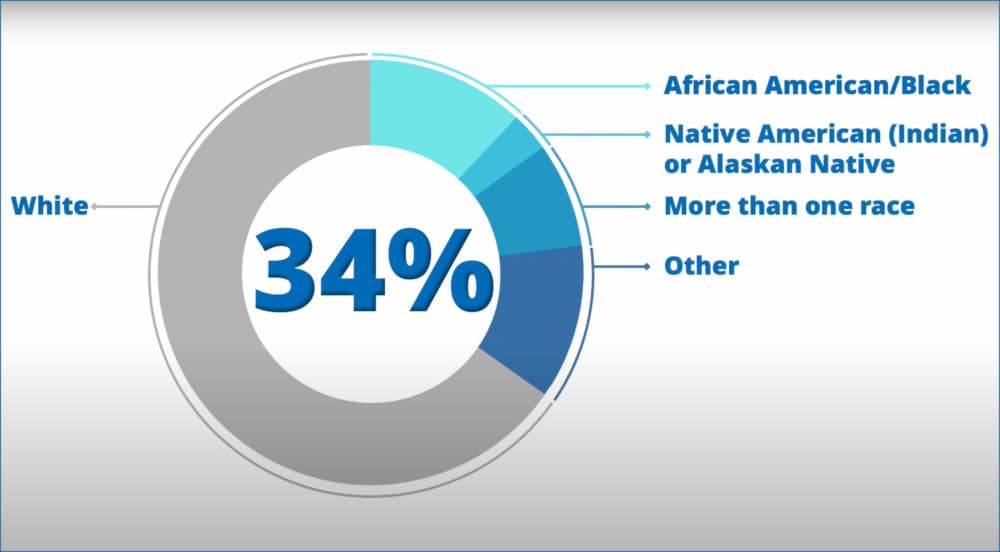

The Rhode Island trial also suggests pharmacy-based addiction care could help fix a disparity in addiction care. Patients who fill prescriptions for buprenorphine, considered the gold standard for treatment of an opioid use disorder, are overwhelmingly white. In contrast, 34% of the study participants identified as people of color, which Green called a surprisingly hopeful outcome.

Pharmacists made a number of adjustments to help patients during the study. They gave participants lock boxes to prevent the theft of medication that brought Mike into the study, or in some cases kept a patient’s buprenorphine on site. The patient would come in every day to get their dose.

“With this demographic, it’s not always a straight line,” said Terranova, “it’s not: This is the plan, this works for everybody.”

Genoa COO Tasha Hennessy called the study results encouraging and said in an email that the company is open to participating in research that “provides patients with access to the treatment they need.”

Green, at Rhode Island Hospital, is looking for a way to expand the pilot.

“It was heartbreaking for pharmacists to have to say good-bye to their patients and connect them to usual care, knowing that the failure of usual care was one of the reasons people were inducted [on buprenorphine] through this path,” Green said. “We can’t do studies like this and leave patients hanging.”

This segment aired on January 11, 2023.