Advertisement

Commentary

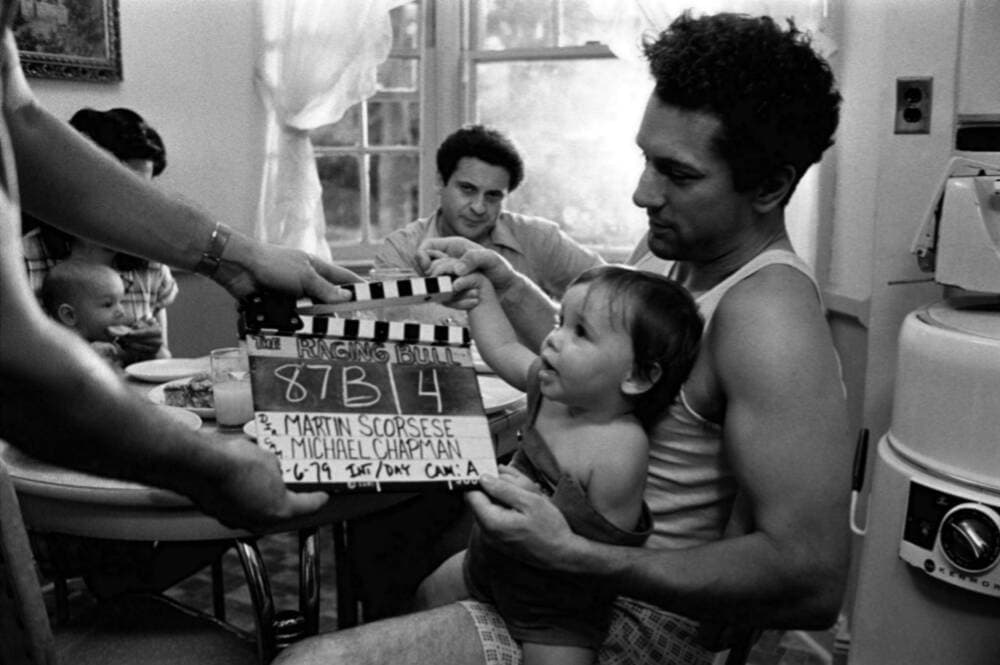

Martin Scorsese’s seething psychodrama 'Raging Bull' returns to the Coolidge

In his 1980 Village Voice review of Martin Scorsese’s “Raging Bull,” critic Andrew Sarris admitted being puzzled as to “why anyone would want to make a movie about Jake LaMotta.” This was a sentiment shared by many at the time. The Bronx-bred prizefighter and former middleweight champ was an especially unsavory sort, a legend in boxing circles for his brute viciousness and an almost superhuman ability to withstand punishment in the ring. Married seven times, LaMotta admitted to throwing a fight for the mob and served six months on a Florida chain gang after being convicted of procuring an underage girl at one of his clubs. This was hardly the kind of historical figure one expected to see in a Hollywood biopic. Even the head of the studio making the picture called him “a cockroach.”

And yet “Raging Bull” — which returns to the Coolidge Corner Theatre this week in a new 4K digital restoration — is one of the great American films, not for what it tells us about LaMotta, but for what it tells us about ourselves. Scorsese’s masterpiece is a searingly personal exploration of jealousy and self-loathing, seen (sometimes literally) through the eyes of a man who considers himself so unworthy of love that he cannot help hurting those who care about him most. He’s enraged by affections he assumes must be suspicious or soiled in some way, because what could these people see in such a wretch? None of this is articulated or explained, but instead brilliantly evoked via Robert De Niro’s career-topping performance and some of Scorsese’s most fearlessly subjective filmmaking techniques. The movie is unflinching in its depiction of this “cockroach,” in its horrors daring us to see that there but for the grace of God go we.

De Niro had been hounding his friend and frequent collaborator about the project for years, but the famously sports-averse director could find little of interest in LaMotta’s memoir. It wasn’t until Scorsese’s spiraling drug addiction landed him at death’s door on Labor Day weekend in 1978 that the character finally clicked for him. He was in rough shape at the time, coming off his second divorce and the failure of “New York, New York,” the filmmaker’s fascinatingly misguided attempt to make a domestic abuse drama as an old-timey MGM soundstage musical. (Featuring De Niro smacking around Liza Minnelli between catchy Kander and Ebb songs, it’s one of those uniquely 1970s movies that should come with a co-directing credit for cocaine.)

Scorsese’s first and only attempt to direct a Broadway show starring then-muse Minnelli had ended with his ignominious departure from the production. Since then he’d been rooming with The Band’s guitarist, Robbie Robertson on an epic Mulholland Drive sex, drugs and rock n’ roll binge that had already become the stuff of New Hollywood legend even before blood started gushing out of Scorsese’s nostrils and eyeballs. The filmmaker was in the hospital recovering from massive internal hemorrhaging when De Niro came to him again with “Raging Bull.” That’s when Scorsese decided that he would “make the movie about me.” Over the years, he’s referred to the film as his semi-autobiographical attempt at an exorcism, and it’s oddly poetic that a guy bleeding out on the inside would spill his guts all over the screen like this as therapy.

Like so many Scorsese movies, “Raging Bull” can be seen as an extension of the director’s award-winning New York University student short “The Big Shave,” in which a man stands before a mirror with a razor, nonchalantly cutting his face to bloody ribbons until the white bathroom is awash in crimson. Then he slits his own throat. The director has said the film was intended as a metaphor for America’s involvement in Vietnam, but in retrospect, it was the birth of the filmmaker’s favorite kind of protagonist: a guy who will not stop hurting himself.

Scorsese’s “Taxi Driver” writer and sometime soulmate Paul Schrader figured out the structure for the screenplay, scrapping all of LaMotta’s early experiences, telescoping events and compositing characters to focus on Jake’s relationships with his brother Joey and second wife Vicki. For a decades-spanning biopic, it’s an incredibly claustrophobic picture — taking place primarily in cramped kitchens and tenement hallways. Scorsese evokes the postwar New York City of his childhood via carefully chosen close-ups of period props, restricting the scope to keep the movie’s perspective as narrow as its protagonist's. Even at the height of Jake’s fame and fortune, it feels like he’s never gotten out of the neighborhood.

Advertisement

After decades on the fringes of the entertainment industry, Joe Pesci had by most accounts given up on show business and was working at Amici’s restaurant in the Bronx when he got the phone call that changed his life. De Niro had seen him on television in a low-budget movie called “The Death Collector” and wanted him to audition for the role of Joey. Pesci was already pushing 40 and too old for the part, but this has never been much of a concern in Martin Scorsese movies, where we generally just accept that the characters are whatever age the movie tells us they are. Besides, Pesci’s chemistry with De Niro was instantaneous. Something electric occurs whenever these two share the screen, a reaction so precious that it’s understandable — however disappointing — that they’ve only worked together a handful of times. Pesci’s voluble pipsqueak energy runs counter to De Niro’s coiled menace, making their improvisations as the LaMotta brothers some of cinema’s greatest knucklehead duets.

De Niro famously gained more than 60 pounds to play LaMotta in scenes of his late-life decadence, a feat the actor has only half-kiddingly attributed to Scorsese’s mother Catherine’s cooking. Over the years, this kind of stunt has become catnip for awards-giving bodies and swaggering young actors — Christian Bale made an early career out of it — but it obscures the full scope of De Niro’s brilliance. He’s a masterful technician, but there’s so much more to his performance than a physical transformation. Jake is a terrifying brute, but he also can be childlike and occasionally even endearing. When he cries, it’s in big, blubbery baby-ish sobs that catch me off-guard every time I see the picture. De Niro’s dim, haunted eyes always look as if he’s fighting off ideas he doesn’t want to be having, thinking about things he’d rather not be thinking about.

Cathy Moriarty’s Vicki LaMotta is taller than her husband, and in a lot of the early domestic scenes, comes off as more powerful than the angry, insecure fighter. The 19-year-old actress has an aloof presence beyond her years, carrying herself as if resigned to this lousy marriage and doing her best to get through it without making a fuss. But we’re so hard-wired into Jake’s twisted headspace she is never allowed to feel available to us. Vicki is seen almost exclusively in slow-motion evocations of his paranoia: standing too close to scuzzy guys from the neighborhood who give her kisses on the cheek that last a little too long. She’s an idealized, magazine pinup dream of which Jake feels undeserving, so he’s somehow got to drag her down to his level. (Before “toxic masculinity” became a buzzword, we had Martin Scorsese movies.)

So much of the movie is a seething psychodrama that our only emotional release comes in the ring. It took ten weeks to shoot the ten minutes of boxing footage that we see in “Raging Bull,” each bout designed in a different, increasingly expressionistic style. Other movies make us spectators of the sport. Scorsese keeps the camera on the canvas, so we’re always inside the ropes with Jake. The fights progress from frightening to phantasmagoric, the soundtrack swelling with roaring animal noises while flashbulbs pop off like rifle fire. Punches in the picture land with sickeningly wet thuds, while Michael Chapman’s high-contrast black-and-white cinematography makes the arenas resemble mid-century tabloid newspaper crime scene photos. These scenes in no way resemble the actual act of boxing, but are instead an extremely Catholic filmmaker’s idea of a penitential rite. In the ring, Jake masochistically accepts his punishment for all the anguish he has caused outside of it. It’s the only place where he feels like he gets what he deserves.

The film reunited Scorsese with his NYU colleague Thelma Schoonmaker, who edited his first film “Who’s That Knocking at My Door?” in 1967, a few years before the two wound up working on Michael Wadleigh’s “Woodstock” documentary together. (My favorite Schoonmaker quote came when, after winning her third Oscar for “The Departed,” she was asked how such a nice lady could edit such violent gangster pictures. She answered, “Ah, but they aren’t violent until I’ve edited them.”) She’s cut all 18 of the director’s dramatic features since “Raging Bull,” in what is no exaggeration to call one of the most fruitful and important collaborations in cinema history. It’s impossible to imagine the propulsive rhythms of a Scorsese picture without Schoonmaker’s staccato editing patterns.

So why would anyone want to watch a movie about Jake LaMotta? Why should we spend two hours with this wife-beating savage? Who cares about this abuser, this criminal, this “cockroach?” Well, sometimes great art forces us to recognize aspects of our personalities that we would rather not acknowledge. Sometimes such extremities allow us a better understanding of ourselves and the people in our lives who are suffering. It would be several more years before Scorsese was finally able to extricate himself from the cycles of addiction and spiritual torment that fueled the making of “Raging Bull.” But as he confesses through a quote from the Gospel of John that ends the picture, "Whether or not he is a sinner, I do not know… All I know is this: once I was blind and now I can see."

“Raging Bull” opens at the Coolidge Corner Theatre on Friday, May 7.