Advertisement

Years of alleged abuses by Fall River cop reveal limits of internal police investigations

Editor's note: This story references offensive remarks about race and sexual assault that some readers may find upsetting.

On February 12, 2019, the Fall River police responded to a 911 call at an apartment building where neighbors were having an argument. A man standing outside, David Lafrance, was briefly placed in handcuffs while officers went inside to investigate. When they came out, they began to uncuff Lafrance to let him go. But as one officer turned the key in Lafrance’s cuffs, another officer, Michael Pessoa, hit Lafrance hard in the face.

Instead of being released, Lafrance was arrested for assaulting an officer and placed in the back of Pessoa’s police cruiser, where Lafrance said Pessoa punched him in the face again.

Pessoa was investigated for misconduct shortly after — a regular occurrence throughout his 19-year police career. But unlike the investigations that cleared Pessoa of similar charges in the past, Lafrance had a video of their encounter, obtained by a surveillance camera at his apartment building, which he shared with investigators outside the Fall River Police Department.

The Bristol County District Attorney’s office dropped the charges against Lafrance and prosecuted Pessoa instead — for assaulting Lafrance and filing false reports justifying his arrest. When Pessoa went on trial in May, he was convicted and sentenced to at least 18 months in prison. During her closing argument to the jury, Assistant District Attorney Gillian Kirsch emphasized the uphill battle that civilians face in reporting police misconduct.

“Without this video,” Kirsch said, “who’s going to believe the statements of David Lafrance over four sworn police officers?”

Allegations and dismissals

A review by The Public’s Radio of court records and internal affairs documents, some of which were destroyed by the Fall River Police Department and recovered through other sources, revealed that at least twelve other civilians accused Pessoa of excessive force before Lafrance. Records show Pessoa was never disciplined for those incidents until the DA started probing Pessoa’s past, even though patterns of concerning allegations had been clear to Pessoa’s superior officers.

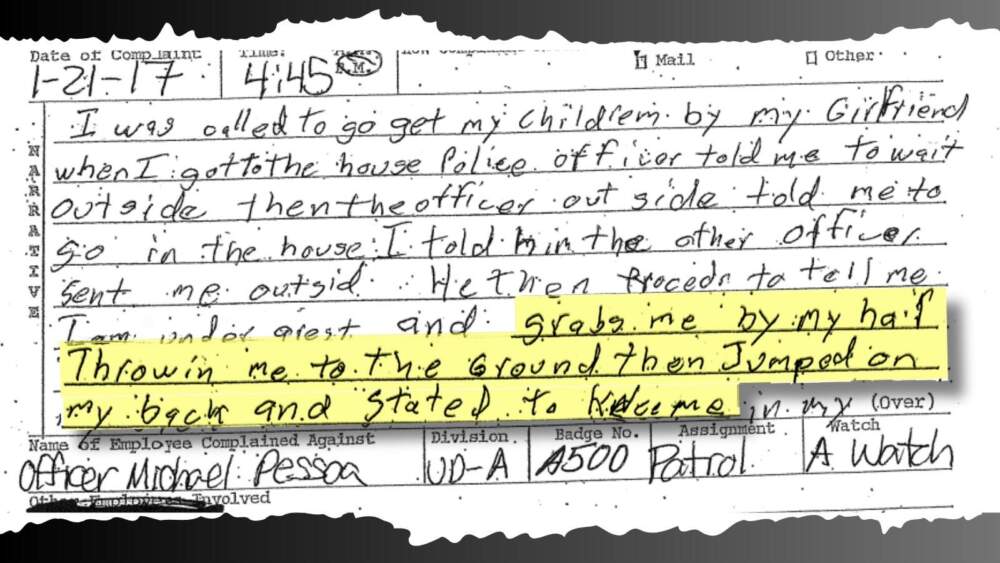

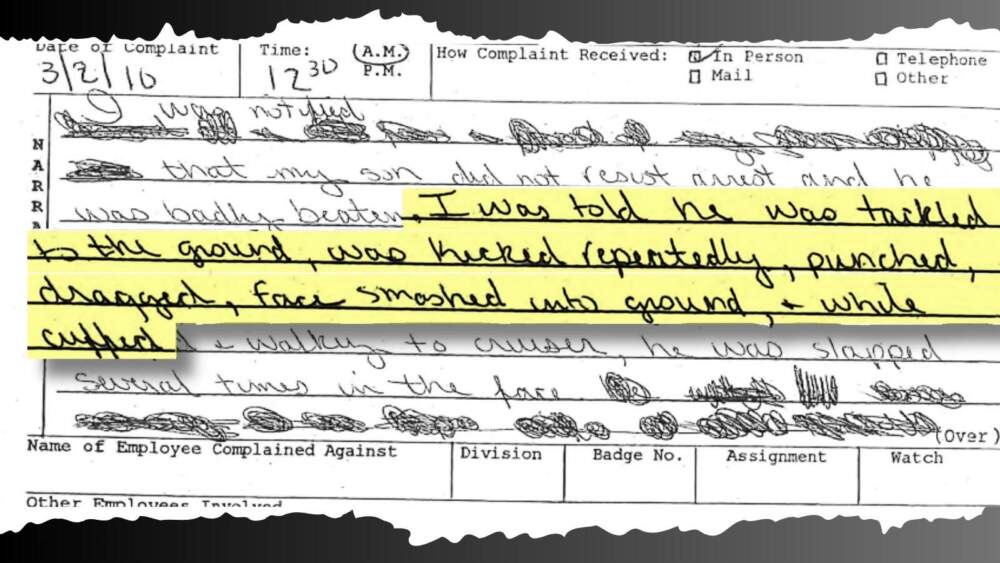

Civilians reported Pessoa for placing them in chokeholds at least three times, and bystanders repeatedly claimed that Pessoa would break their phones if they tried to film arrests. Other civilians complained of serious injuries.

In 2006, a teenager questioned about a stolen ring claimed Pessoa and another officer beat him so badly he suffered a lacerated spleen, causing him to vomit and pass out hours later in a jail cell.

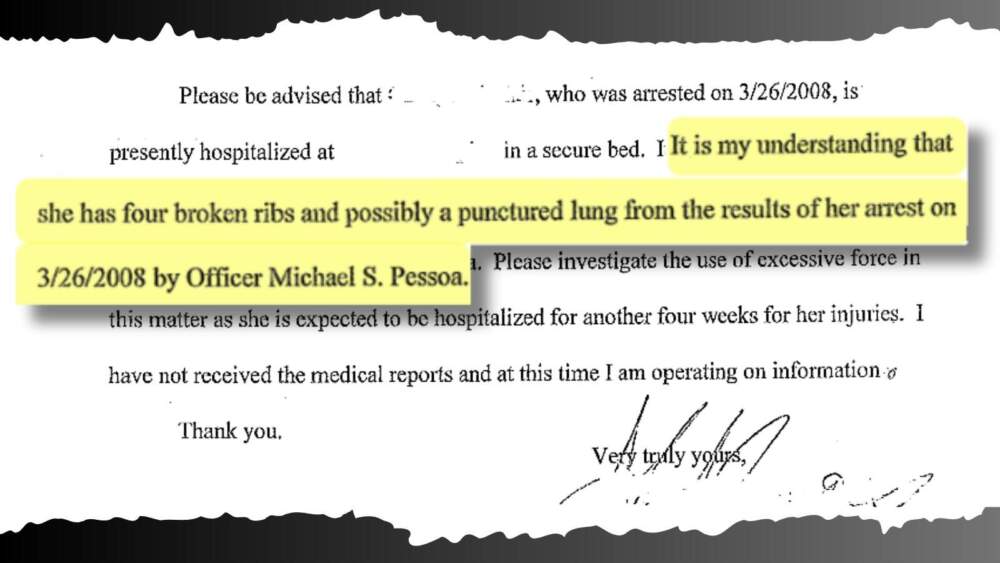

In 2008, Pessoa arrested an alleged sex worker and broke several of her ribs, a use of force that an internal investigator later deemed justified. The investigator wrote that Pessoa’s “knee strike” to the woman’s ribs “did calm her down.” Pessoa said the woman spat on him inside a police car and bit his hand when he pulled her outside to adjust her handcuffs.

In 2014, Pessoa broke a man’s shin while responding to an argument between neighbors, leaving him unable to walk without a cane, according to a judge who recently reviewed the case. Pessoa said the man had been yelling and approached him “chest to chest.”

Pessoa also received complaints that described him making openly racist and sexist remarks to civilians on duty, which were dismissed as unfounded by internal investigators. In one incident from 2016, a woman found unconscious near a Fall River bar told police she had been raped. In a complaint she later filed with the police department, she said Pessoa responded by saying, “No one would want to rape your nasty a** and if they did, you deserve it.”

Advertisement

As the number of complaints and lawsuits against Pessoa began to distinguish him from every other officer in the department, Pessoa was awarded an extra $2,900 per year to serve as a field training officer, a role responsible for teaching younger officers the best practices of police work in Fall River.

Meanwhile, the City of Fall River footed the bill for at least $344,000 in settlement payments for people who accused Pessoa of excessive force, a figure that could rise significantly in the coming years. Two more lawsuits are still pending in court, including one filed by David Lafrance.

Pessoa’s ability to remain on the street as a patrolman for nearly two decades despite these frequent complaints of abuse offers a window into how the Fall River Police Department polices itself. Internal affairs experts contacted by The Public’s Radio said the findings point to a problematic leniency among the department’s internal investigators that underscores similar failures in police departments nationally.

Fall River Police Chief Paul Gauvin declined to be interviewed about Pessoa or the department’s internal affairs division, known as the Office of Professional Standards, where he worked from 2008 to 2011 prior to becoming chief.

How internal investigations work

In many professions, repeated allegations of abuse or inappropriate behavior lead swiftly to an employee’s termination. But police officers typically work under strong employment protections meant to shield them from the kinds of false allegations they are potentially more vulnerable to.

To report a police officer for misconduct, a civilian is often asked to write out their allegations on a complaint control form. Internal investigators who work for the police department review the form and gather evidence to determine whether to sustain or dismiss the allegations.

The police chief then uses their report to decide whether to discipline any accused officers. Most serious disciplinary measures handed down by the chief, including termination, can later be appealed by police officers to independent arbitrators who operate outside the control of the police department.

Thomas Nolan, a retired professor of criminal justice and former Boston police lieutenant who worked in a unit investigating officer-involved crimes, said Pessoa received “an extraordinarily excessive number of complaints for an officer.”

Most of the complaints, however, were not sustained by Fall River’s internal investigators.

“Usually an arbitrator will say that if there’s no sustained complaints, an officer shouldn’t be fired,” Nolan said. “What confounds police chiefs is their inability to terminate these guys who clearly have to go, because they're going to get their jobs back through arbitration.”

A national study of arbitration cases published by the Vanderbilt Law Review in 2021 found that nearly half of previously terminated police officers get their jobs back through arbitration.

Barriers to police accountability in Fall River

Most complaints civilians file in Fall River are dismissed much earlier in the process. For every ten complaints, only one is sustained, according to a five-year analysis of the most recent complaint data the police department provided.

Internal affairs experts contacted by The Public’s Radio said other police departments, including Boston’s, have recently reported similar clearance rates for civilian complaints. But these experts said a review of Pessoa’s records revealed barriers to police accountability in Fall River that are rarely seen elsewhere in Massachusetts.

“There's one policy that I have not seen anywhere else,” said Howard Friedman, an attorney with 40 years of experience bringing misconduct cases against Massachusetts police departments, “and that is their policy of destroying internal affairs records after a certain number of years.”

Under a protection in their union contract, Fall River’s police officers can purge even the most egregious complaints from their internal affairs file after five years, allowing them to essentially wipe their slate clean.

“In order to discipline police officers, you need to show progressive discipline. You can't start off by firing someone,” Friedman said. “You've got to document the issues with the officer so that you can eventually say that this person was legitimately terminated.”

The police union contract in Fall River also empowers officers to challenge mandated drug tests. Through a process known as a reasonable suspicion review, officers can appeal their chief’s orders to be drug tested to a committee of fellow officers, who make the final decision on whether the test can move forward.

Pessoa availed himself of this protection in 2010, after a civilian told internal investigators that he and Pessoa were buying steroids from the same dealer.

“We believe we have a credible witness,” the investigator wrote in handwritten notes obtained by The Public’s Radio. The investigator noticed “increased alleged aggressiveness” and “observed weight change in physical stature of Officer Pessoa.”

But Pessoa’s colleagues halted the drug test after he called for a reasonable suspicion review, a proceeding there is no remaining public record of. The investigator ultimately classified the steroid allegations as “not sustained,” citing “insufficient proof to confirm or refute the allegation.” The complaint was later purged from Pessoa’s file.

Rare instances of discipline

On the few documented occasions where Pessoa faced internal discipline, it was mostly for complaints raised by fellow police officers.

In 2012, a Fall River police officer ended a romantic relationship with Pessoa and applied for a restraining order. She stated in an affidavit that Pessoa let himself into the house they used to share, screamed at her and threw her belongings around. The female officer said she tried to get in her car and leave but Pessoa moved his car behind hers, effectively trapping her. “He harassed me all of the next day while I worked,” the officer wrote in the affidavit.

In a negotiated disciplinary agreement, Pessoa admitted to engaging in “conduct unbecoming an officer,” but the section describing the discipline he received has been redacted. A spokesperson for the Fall River Police Department would not provide further details. Pessoa, however, remained on the force, while the female officer found a job with another police department in a nearby town.

In 2014, Pessoa faced discipline again for an incident involving a female officer from the Raynham Police Department who he dated. Pessoa admitted to posting a racist tirade on her Facebook account about a birthday party the professional basketball player Dwayne Wade threw on a yacht.

“Every white girl on that boat should be ashamed of themselves…stupid money hungry whores,” Pessoa wrote in the Facebook post. “These guys are a bunch of dumb black thugs who are lucky they can shoot a basketball, if not for that they would either be dead or in prison.”

Pessoa’s girlfriend initially faced discipline from her own police chief in Raynham before Pessoa admitted to writing the post. He received a five-day suspension. The complaint was later purged from his file.

How Michael Pessoa lost his job

The incident that ultimately ended Pessoa’s police career was never reported as a civilian complaint. David Lafrance shared the video of Pessoa beating him outside his apartment building with the Bristol County District Attorney’s Office, bypassing an internal investigation by the Fall River Police Department his attorney said there was little upside in pursuing.

“When you send in a civilian complaint to the police department, they do whatever they want with it,” said Carl Ricci, an attorney representing Lafrance in a pending civil lawsuit against the Fall River Police Department. “You don't even know if they’re doing what they’re supposed to do because they could answer you in a way that you can't check.”

At Pessoa’s criminal trial, prosecutors spent several days cross-examining the other police officers involved in Lafrance’s arrest, pinning down details of how and why they corroborated Pessoa’s false statements. One of the officers, Sean Aguiar, said Pessoa convinced his younger colleagues to change their reports by telling them their supervisors would not accept the paperwork until all their reports were consistent.

“Blue blood runs deep,” said Kirsch, one of the prosecutors, during her closing argument. “What started out as a routine call quickly developed into a cover up. All of them would ultimately support the defendant's false narrative of that night.”

Reforming internal affairs

The jury convicted Pessoa of assault and battery, filing a false report, and other criminal charges, leading to a prison sentence of at least eighteen months. The district attorney’s office is now prosecuting two other alleged cases of police brutality from Pessoa’s past.

But even as Pessoa faces consequences in the criminal court system, critics say his ability to evade internal discipline within the Fall River Police Department for so long points to lingering problems in how investigators there treat civilian complaints.

“The whole system, unfortunately, is designed more to protect the police than to protect the public,” said Friedman, the civil rights attorney who has twice won monetary settlements for clients who pursued excessive force lawsuits against Pessoa. “As a result, I advise clients not to file complaints.”

Keith Taylor, a former internal affairs investigator in the New York City Police Department and an adjunct assistant professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, said the leniency of Fall River’s internal affairs investigators likely emboldened Pessoa’s behavior.

“It looks like this officer was really not concerned about any repercussions for calling people inappropriate names or using excessive force,” Taylor said.

Outside law enforcement agencies are now pursuing other cases against Fall River police officers as well. Last winter, the FBI arrested Officer Nicholas Hoar for allegedly beating a civilian and covering it up with false reports. Protests over fatal police shootings of young men of color in 2017 and 2021 have also sparked allegations of police cover-ups, contributing to mounting pressure for local police reform.

This June, Fall River police officers began wearing body cameras, a technology that can give investigators more evidence to work with when civilians report misconduct. The cameras are also seen as a way of protecting officers from false complaints.

The reform followed broader movements for greater police accountability in Massachusetts. In 2020, the state legislature created the Peace Officers Standards and Training Commission, a new state agency that has the power to “decertify” police officers. Enrique Zuniga, the POST Commission’s founding director, said decertification is a form of termination that cannot be overturned by police chiefs or arbitration boards.

Police departments now forward the civilian complaints they receive to the POST Commission for additional scrutiny.

“POST is building on the system that's existing, and I think that's the intention of the statute: to get the complaints and the investigative reports that police agencies do and ensure that they're being done in the manner that they are intended,” Zuniga said.

The POST Commission also began receiving its first complaints from civilians that bypass local police departments altogether, opening a new door for reporting police misconduct in Massachusetts.

“The hope and the expectation is that ultimately this will be a statewide entity that can subsume this function,” said Nolan, the retired professor who worked in the Boston Police Department’s anti-corruption unit. “But that’s many years out.”

“One day,” Nolan said, “we’ll look back and say, who thought it was a good idea to let police departments investigate their colleagues for allegations of wrongdoing?”

The Public’s Radio in Rhode Island and WBUR have a partnership in which the news organizations collaborate and share stories. This story was originally published by The Public's Radio.