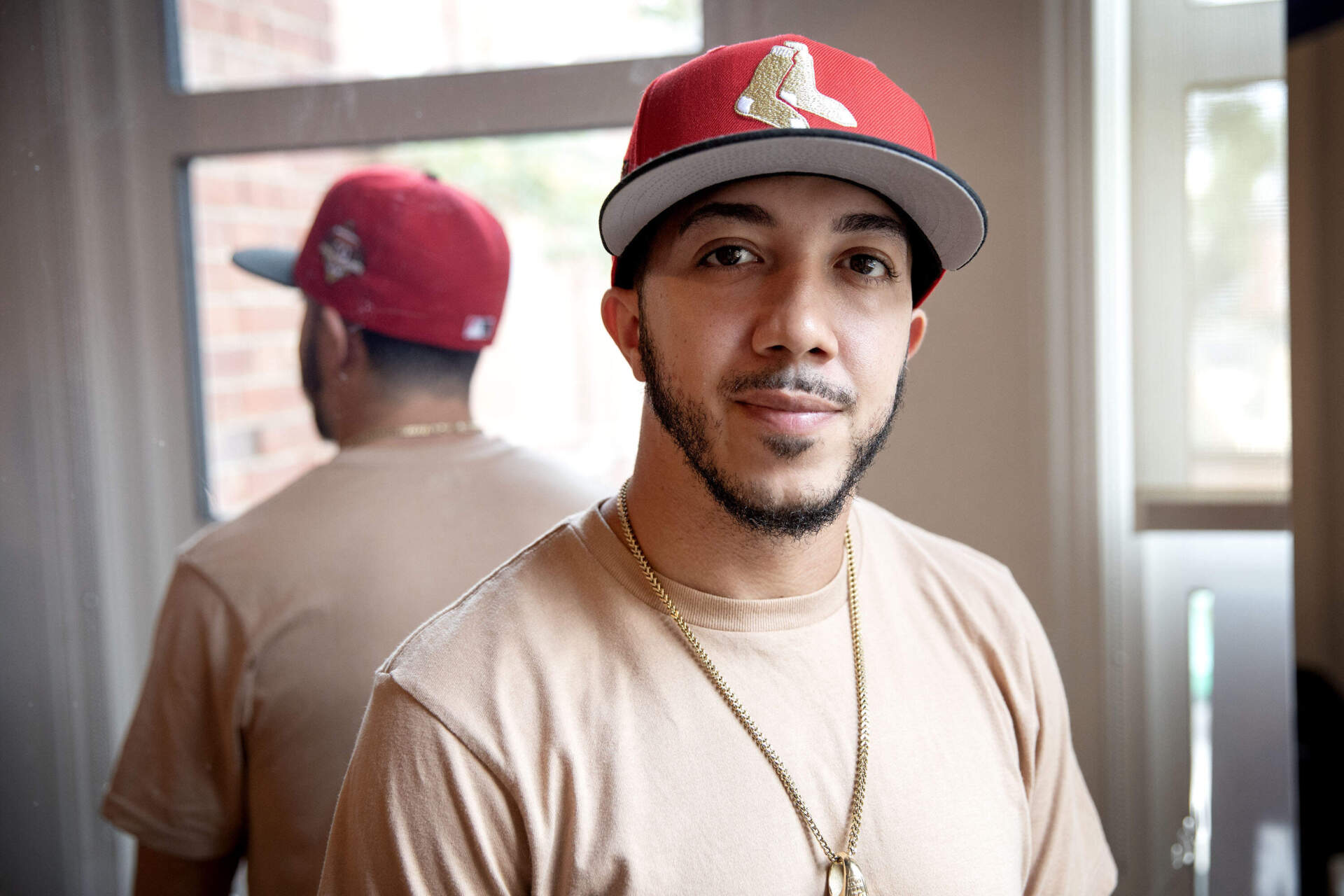

Olympic hopeful Alex Diaz brings optimism and originality to breakdancing

Alex Diaz shines as a breakdancer.

His b-boy name is El Niño. It comes from his fast-paced and aggressive style, which personifies the tropical storm. His talents have made him a Red Bull-sponsored athlete, multiple-time international breakdancing champion and, more recently, an Olympic hopeful.

“I'm just a kid from Roxbury. Humble beginnings, grew up with a mother in Section 8 [housing]. So it’s just like, nothing's impossible,” Diaz, 33, said. “If you really want it, you really have to focus because anything that's worth something is not going to be given to you.”

He practices and teaches at a dance studio in Harvard Square. It’s home to the Floor Lords dance crew, of which Diaz is president. The Floor Lords have been recognized for their innovation in the world of breakdance since 1981. Diaz even has a few original dance moves he created, like his cannonball head spin.

“I'm known for that move, which is basically like a head spin with my leg crossed. But I drop to my head, no hands,” he explained. “It's kind of a dangerous move. If you do it wrong, you would just hit your head and knock yourself out.”

He invented it after watching the 1978 kung fu classic, “Drunken Master.” Diaz considers originality to be sacred. “The golden rule of hip-hop is no biting,” said Diaz — biting is slang for stealing. He said he refuses to compromise on that rule, even after someone offered him 100 euros to “rent” one of his moves during a trip to Bordeaux, France.

Diaz grew up molded by the world of hip-hop. His uncle, Lino Delgado, aka B-Boy Leanski, was a founding member of the Floor Lords and president before Diaz. When Diaz was a toddler, Delgado would spin him on his head like a top. He took Diaz to dance competitions at a young age to observe. Then, one day in New York, Diaz decided to compete.

“He was taking on these adults and people were just going crazy,” Delgado recalled. “By the end of the night, everybody knew his name. The whole crowd was screaming his name.”

At only 8 years old, Diaz finished in third place. And he’s kept his foot on the gas since that first competition.

Advertisement

Diaz went on to perform alongside artists like Missy Elliott, LL Cool J and 50 Cent. This summer, he accompanied Raekwon the Chef of the Wu-Tang Clan at the Red Bull BC One Cypher USA event in Philadelphia.

In addition to dancing, Diaz looks out for the longevity of the art. He makes it a point to train the next generation of breakers, like Alan Kuang, a senior at Boston University studying theater.

“He's given us a lot of opportunities,” Kuang said. “He's really busy, of course. He's always traveling and competing and judging. But when he's at the studio, he's always trying to push us.”

Kuang considers Diaz a big brother, and counts himself fortunate to be working under Diaz in the competitive world of breaking. “I want to take it and be able to hopefully make money and make it maybe a career, if possible,” Kuang said.

Making a living breakdancing isn’t easy. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates there are fewer than 9,000 professional dancers in the country, regardless of style. “Ninety-five percent of the breakers are dancing as a hobby and they have a regular job,” Diaz said. He’s sure they would all love to be making money dancing instead.

With breaking set to become an Olympic sport at the 2024 Summer Olympics in Paris, dancers from all over the globe could have their art legitimized and financially supported. But the addition of breaking to the Olympic roster has seen some pushback from older breakers. Diaz said there were “people feeling like the Olympics is going to water down our culture.”

But, he pointed out, making money in the arts has never come easily. Reframing dancing as a sport could ensure longevity and financial stability. “There's money in sports, but there's not a lot of money in art,” Diaz said.

A torn meniscus sustained while preparing for a competition last year may stand in the way of Diaz breaking for gold. But he said he’s worked too hard to give up. He remains determined to compete on that famed international stage, or at least have a hand in it.

“Even if I don't do it, I have to keep trying. Even if I never make it, I have to keep trying,” he said. “Or, maybe the universe wants me to train somebody, and I train the next gold medalist from the U.S. I want it to be a part of my legacy.”