Advertisement

Peabody Essex Museum conjures the spirit world in new exhibit

Shannon Taggart spent almost two decades researching Lily Dale, New York, a rural hamlet home to a robust spiritualist community. During one of her visits, she shot a photo of a woman in the throes of a transfiguration session, sitting under a red light to find out if she could see spirits.

“I tried to make a very straightforward image of this woman with her red flashlight,” Taggart said. “Instead, I got an image that showed a second face, which was very synchronistic with the reports of the invisible reality.”

The photo, which appears in Taggart’s book called “SÉANCE,” is displayed at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem in an exhibit called “Conjuring the Spirit World: Art, Magic, and Mediums,” which runs through Feb. 2. The exhibit explores our fascination with the supernatural, featuring art and objects that mediums and magicians used during the Spiritualism movement in the 19th and 20th centuries, as well as work by contemporary artists and magic performances.

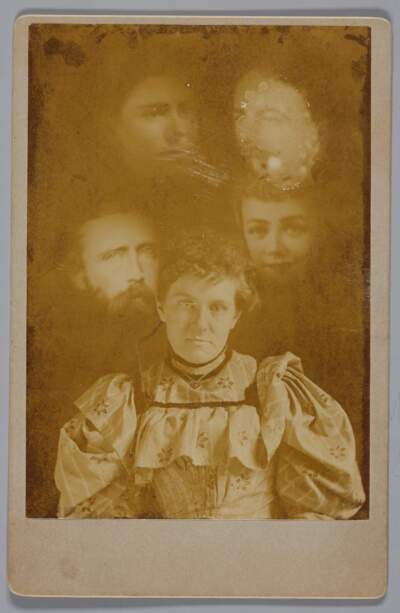

George Schwartz, curator-at-large at PEM, said the exhibit and accompanying book of the same name stemmed from his research on Arthur Conan Doyle, Margery the Medium and Harry Houdini, their connections with each other and the objects they used and collected. The exhibit showcases posters advertising performances, spirit photographs, portraits, books and newspaper clippings, as well as objects like a rapping hand people used to detect the presence of spirits, mourning jewelry, a death mask and more. Artist Tony Oursler, who has a phantom multimedia piece in the show, loaned some of those objects.

“By looking at these objects, exploring the stories behind it, we get a richer sense of this time period and this movement,” Schwartz said.

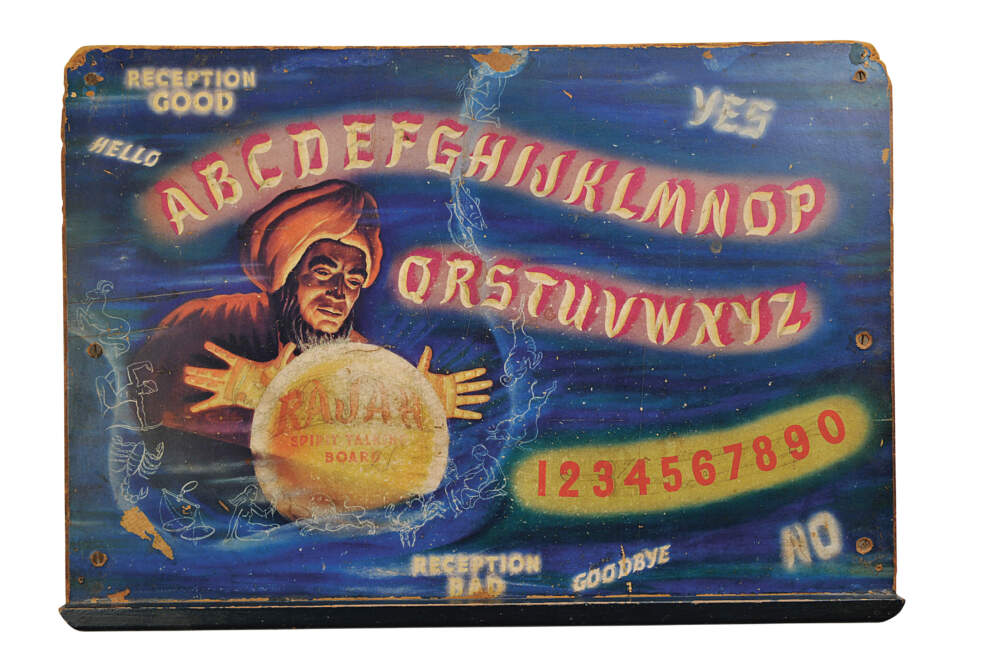

If any object from the Spiritualism movement has withstood time, it’s the Ouija board. According to John Kozik, owner and curator of the Salem Witch Board Museum, the Ouija board was born when people sought to communicate with those they had lost in the Civil War. People used alphabet boards to attempt communication with spirits, who responded by knocking. The automatic writing planchette, featuring a pencil in the front and wheels in the back, worked when a medium channeled a spirit. The planchette then wrote or drew whatever came through. These two devices intersected, leading to the development of the talking board.

In 1890, Charles Kennard from Baltimore created the first mass-produced board, which he called a "witch board." Shortly after, Helen Peters asked the board what it wanted to be called, and it spelled out "Ouija." This discovery marked the beginning of Ouija as the first mass-produced board.

Advertisement

“A brand like Kleenex to tissues, Ouija is to talking boards,” Kozik said.

The Parker Brothers, a Salem-based gaming company now owned by Hasbro, started manufacturing Ouija boards in 1966. Ouija became the first game to outsell Monopoly the following year, with 2 million boards sold.

“People tend to only think of Ouija boards as something used for spirit communication. But in fact, there are boards in the museum that were created here in Salem back in 1920 to read someone else's mind,” Kozik said. “There are boards made to try to speak to your past lives, try to speak to aliens or ... speak to plants and animals.”

The PEM exhibit explores the neuroscience behind the board with a panel explaining the relationship between ideomotor response and Ouija, meaning users unconsciously move the planchette. More panels throughout the exhibit explain topics like perception in the dark and the relationship between the ability to see a specific image within an ambiguous background (like seeing a face in a cloud), called pareidolia, and spirit photography.

Artist Jose Alvarez (D.O.P.A.) has a piece in the exhibit called “The Seer,” a painting with “an alternative energy or being that is seen coming through in this firmament of forms and light,” the artist said. Museum visitors can also view videos of his performance art, which he performs with a crystal, channeling the spirit of a shaman named Carlos.

Performance was central to the Spiritualist movement. In 1856, the Davenport brothers created a spirit cabinet routine where they were bound to chairs with their legs and arms behind their backs with instruments thrown into the cabinet. After the curtains were drawn, the instruments made a cacophony of noises and luminous hands emerged, allegedly proving spirits were present. When an assistant opened the doors to the cabinet, the brothers remained in the same position.

Anton James Andresen and Evan Northrup, both magicians from Salem, will perform at PEM on Saturdays through the exhibit's run. Northrup, known for theatrical performances, will enact a modern interpretation of the spirit cabinet routine with the curtains open, letting viewers see if he can make objects move on their own accord.

“I think the reason Spiritualism has kind of hung around so long and has captivated people in relationship to magic, is this conflict or this friction between seeing something and knowing something,” Northrup said. “It's questioning our belief systems in some way, and sometimes it's very small, and sometimes it's quite profound.”

When it comes to performance, Schwartz added that underrepresented communities shone. In 1849, Henry “Box” Brown, who was enslaved, mailed himself to freedom in a packing crate. “He started to become part of the abolitionist circuit,” Schwartz said, “and wrote an account of this whole escape, and he would speak about it.”

The movement also established women as leaders. Mediumship granted women the ability to wield public influence at a time when they had limited opportunities to speak publicly, Schwartz noted. While magic was a male-dominated field, some very high-profile magicians were women, sometimes more successful than men. “Creating this persona of a medium or magician sometimes allowed people to reinvent themselves,” he said.

Notably, the first women’s rights convention in the U.S. took place in Seneca Falls, New York in 1848, the same year the Spiritualist movement kicked off in Rochester when the Fox Sisters produced knocking sounds, allegedly messages from a spirit.

“You might have your opinions one way or the other about the validity of Spiritualism, this idea that you can communicate,” Schwartz said. “But come in and explore, look at these objects, hear these stories and see what you think coming out. Maybe suspend your disbelief for a moment, if that's the case.”