Advertisement

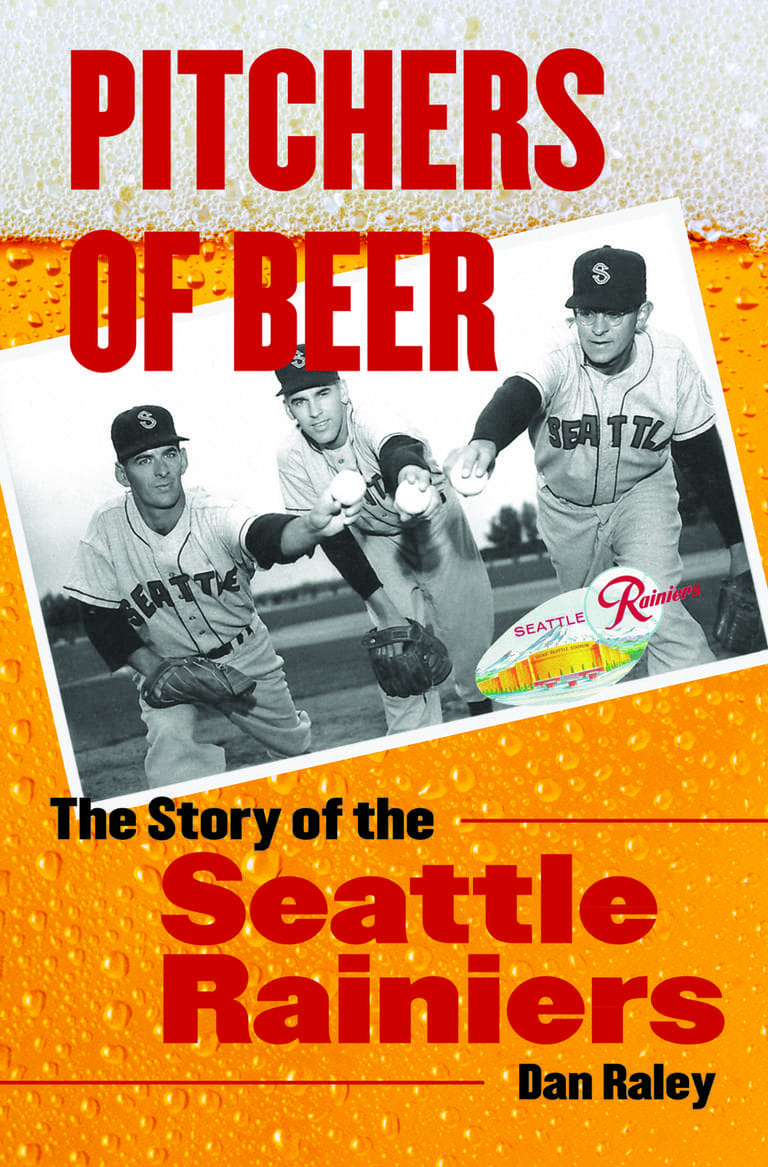

'Pitchers Of Beer: The Story of The Seattle Rainiers'

Resume

In the winter of 1941, Seattle’s minor league baseball team was looking for a manager. The applicants included Rogers Hornsby, Grover Cleveland Alexander, and Babe Ruth. Five of the thirteen men who attempted to land the job would eventually wind up in the Baseball Hall of Fame. None of the five got the job.

In his new book, Pitchers of Beer: The Story of the Seattle Rainiers, Dan Raley chronicles the rise and fall of a team that attracted more fans than some of its Major League counterparts.

Guest host Doug Tribou talks with Raley about a team that was owned by a brewer, named for a beer, and captivated Seattle until it became a big-league city.

An Excerpt From Pitchers of Beer

On a Sunday afternoon in the middle of Seattle, a half-dozen federal agents piled out of cars and conducted a raid. Banking on the element of surprise, these men had told no other government agency what they were doing. That would explain why these dour, serious-minded law-enforcement types came face to face with a squadron of uniformed Washington State Patrolmen riding up on motorcycles, sirens blaring, moments later at the same address.

Both groups, unbeknownst to each other, had shown up with a similar purpose in mind: administer justice as swiftly and efficiently as possible. The ensuing scene was hectic, if not hilarious, with so many badge-carrying people scrambling around and aimlessly bumping into each other they could have held a cop convention. Certainly a dangerous criminal ring had to be the target of these competing operations: Counterfeiters? Gun runners? With the world turning more anxious each day, with war approaching, maybe it was foreign spies?

It was September 19, 1937, on an overcast day in the Northwest, when federal treasury agents briskly strode through the gates of the dilapidated Civic Stadium at the foot of Queen Anne Hill. They entered a well-worn baseball stadium, having determined that the Seattle Indians minor-league team was the one threatening the peace, putting everyone on high alert, and necessitating the swift police action.

The Indians were an unhappy, cash-strapped outfit, which, in compiling an 81-96 record and a fifth-place finish in the Pacific Coast League, hadn’t seen this many eager and excited people together in the grandstands all season. Employees working the ticket windows were confronted between games of a season-ending doubleheader against the visiting Sacramento Solons. The feds demanded that outstanding admission taxes be handed over from the accumulated game receipts. They barely had time to identify themselves when the uniformed state patrol officers rode up in more pronounced fashion on behalf of the state tax commission. It seems the Indians were in arrears in paying all of their bills, and people representing different entities were trying to confiscate what they could.

“The feds beat us to it,” one patrolman was overheard saying after rifling through an empty till. “Let’s grab the bleacher gates.” Ticket sellers at the Republican Street windows were approached next, and all of their cash was seized. It might have been the first legalized holdup staged in the city.

Sensing that the quest for available finances was quickly turning into a free-for-all, a member of a third public agency got involved. William “Wee” Coyle, a Civic Stadium administrator and a former University of Washington football quarterback, stuck his hand in a drawer and pulled out $190 for the city. This would pay off most of the team’s outstanding stadium lighting tab. “Now you fellows can fight for the rest,” Coyle teased the deputized bill collectors.

While much of the crowd of five thousand fans was oblivious to this frantic money grab, others wanted their designated cut. “Hey, what’s going on here?” Sacramento manager Bill Killefer yelled from the field. “How about the 40 percent that belongs to us?” Getting no response, Killefer climbed into the stands in search of a lawyer to help the visiting team obtain its rightful portion of the suddenly dwindling gate intake, but his efforts were futile.

The three agencies retrieved what they thought were all of the available funds, but an Indians official had stuffed several bills into the uniform pockets of the team’s first-base coach, hiding money in a place the others would never think to look for it — on the field. While all this haggling was going on over the stadium cash, there also was a heated attempt in the home clubhouse to cut team expenses.

Seattle pitcher Dick Barrett was in line for a $250 bonus if he won twenty games. The round-faced player had entered the season-ending doubleheader with eighteen victories, a commendable total that had brought him an earlier $250 stipend. In this time of rubber-armed pitchers, Barrett was set to throw both games, the second contest scheduled for seven innings following a regulation nine, in an attempt to achieve the maxi- mum performance bonus.

Beleaguered Indians owner Bill Klepper, the man having all of the trouble settling up with his various creditors, ordered field manager Johnny Bassler not to use Barrett again after a 4–1 victory over the Solons in the first game. Money was the

only reason for this decision, and the club officials came close to blows before Bassler shoved the angry Klepper out the door and proceeded to get his team ready for the second contest. The Indians’ starting pitcher for the next game would remain the same, as would the outcome.

Winning 11–2 in the nightcap, Barrett had his twenty victories and collected his incentive money, which he eventually handed over to the supportive Bassler out of gratitude. Bassler was fired that night over the incident, but was likely out of a baseball job even if he had submitted and used different pitchers. Klepper emerged the next day with a black eye, compliments of an unnamed baseball player away from the park.

Rugger Ardizoia, a San Francisco Mission Reds pitcher who would play for Seattle more than a decade later, wasn’t surprised when he heard about Klepper’s last-day shiner. The Indians owner was known for reneging on his financial commitments to players or for paying them late. On an earlier trip to Seattle during that 1937 season, Ardizoia had seen irrefutable proof of this: “We went into the Gowman Hotel on Stewart Street, where we were staying, and a guy named [Bill] Thomas, a pitcher, was chasing Klepper around,” he recounted. “Klepper was hanging onto a light fixture, yelling, ‘Thomas is trying to kill me!’ All Thomas wanted was his paycheck.”

The law-enforcement raids at the ballpark were preceded by warrants filed by the state tax commission a week earlier for the collection of $5,395 in unpaid business and admission taxes, and were reported the following morning in a bold, banner headline stripped across the top of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer that declared: “G-Men Seize Ball Game Cash.” Momentarily overshadowed was front-page news of a planned visit to Seattle, Bremerton Naval

Shipyard, and Bonneville Dam by President Franklin Roosevelt, who was on a speech-making crusade, pushing for his social reform, or what was described in wire-service stories as “his fight for liberal interpretation of the constitution.” What was happening here was a baseball team going on welfare while the nation’s leader was trying to pull the rest of the country off it.

As the authorities filed out of the ballpark with whatever loot they could find, bringing the 1937 season to a comical close, professional baseball in Seattle was listing badly. The local team was bankrupt, facing threatened eviction from Civic Stadium. The makeshift ballpark was a grassless field more suited for football, if not mud wrestling, and hardly something to fight over. Baseball was on life support.

This segment aired on August 20, 2011.