Advertisement

Navajos Leave Footprint On The Diamond

It’s said Geronimo played baseball with his fellow Apache prisoners at Fort Sill, Okla. Today, baseball no longer needs a captive audience in Indian country. Native kids play everywhere, on sandlots, in warehouses, and on turf fields.

Navajos light up social media and messaging networks each time Jacoby Ellsbury comes to bat. On the eve of opening day, Only A Game’s Ken Shulman traveled to New Mexico to meet a Navajo team that uses tribal lore to train quality ballplayers.

Baseball Is About Failure

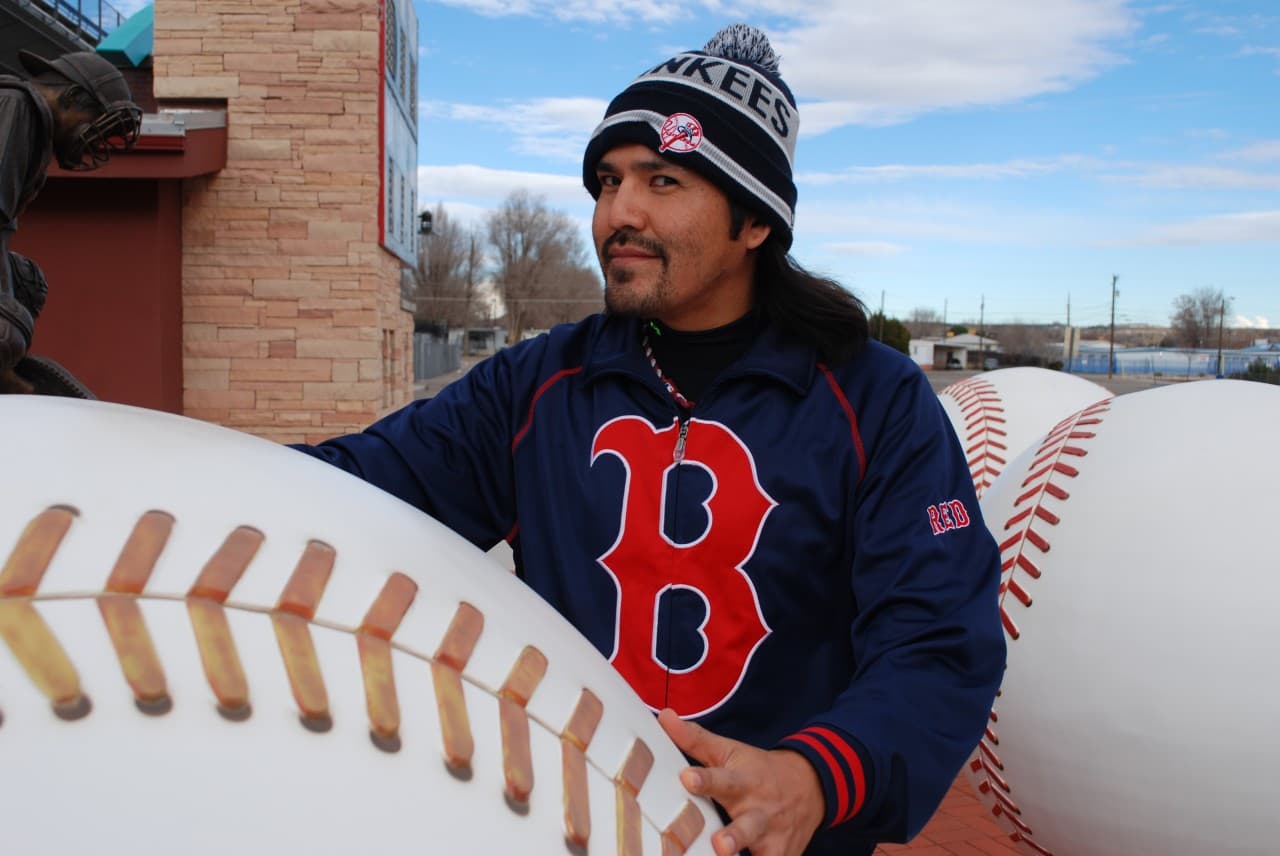

Corey Allison’s in a bit of a spot. The musician from Farmington, N.M., has been a Red Sox fan ever since his cousin Jacoby Ellsbury was drafted by the club in 2005.

Corey’s sister Shawna even sang the Navajo Flag Song at Fenway Park before an April 2008 game. Now that Ellsbury has signed with the New York Yankees, Allison and lots of other Navajo fans aren’t quite sure what to do with their Red Sox loyalty—or their t-shirts, golf bags, hats, license plates, banners, coffee mugs. Corey Allison even has Bo-Sox boxer shorts.

“A lot of ‘B’s’ have been removed, unfortunately,” Allison said. “A lot of the ‘B’ logos, the Red Sox logos. Flags are pretty much at half-mast I guess you can say.”

Navajo Nation may have broken away from Red Sox Nation. But baseball is more popular than ever in Indian Country. Part of that’s due to Ellsbury, and other recent native MLB stars, like pitcher Joba Chamberlain. But part of it has to do with the nature of baseball and with being Navajo.

“Being Navajo is being able to handle the struggles of life and to understand that in order to be successful you’re gonna get knocked down more than once,” said Dineh Benally, a youth baseball coach with teams in Farmington and Albuquerque.

Benally learned baseball as a kid on a reservation in Shiprock, where New Mexico borders with Colorado, Utah, and Arizona. The Four Corners was the Navajo ancestral home until 1864, when the tribe was forcibly marched to a desolate reservation 500 miles away.

Advertisement

“Baseball is about failure,” Benally said. “And I think life is about failure. You’re gonna fail more than you succeed. In baseball, you can hit the ball out of ten times, hit the ball three times you’re considered a Hall of Famer.”

Benally’s had his share of hardship. And failure. Growing up on the reservation was fun. But farm chores often kept him off the ball field. And when he did play, there wasn’t much in the way of coaching. Still, the tall right hander was MVP of his all-Navajo high school team. He pitched two years in junior college. Then he got a break: a chance to make the team at New Mexico State University—and to prove that a boy from the rez could play Division I ball. He threw well in tryouts but was cut on the final day.

“I think about that day, how I was so close to becoming a D-I athlete,” he said. “And it came down to the cut, and, you know, they picked the other kid.”

Naat'aanii

It was tough not making the team. But Benally rallied. He thought about his ancestors on that long walk from Four Corners. And he thought about what he’d learned.

A few years after graduation, in 1999, he started a youth team, to give Najavo kids the type of training he wishes he’d had growing up. He called the team "Naat’aanii," a word that’s hard for Anglos to pronounce. In Navajo it means leader. He scoured the state for native talent, boys born on and off the rez who he could shepherd toward college baseball and maybe even the pros.

“Going to U of A it’s almost like I’m not representing myself, but I’m representing, you know, kind of like my culture,” Vincent Littleman said.

Littleman is one of Benally’s success stories. The Navajo left hander joined Naat’aanii when he was 14. In 2009 he went to the University of Arizona on a baseball scholarship. D-I competition was tough, and there was some culture shock.

“All the players were, when I met them and I told them I was Native American, they were like, ‘Wow you’re Native American,’ and I was like, ‘Yeah, I’m Native American,’ and they were like, ‘Dude you’re the first Native American I’ve ever met.’

“And then they always ask silly questions like, ‘Do you guys still live in teepees? Do you guys hunt buffalo?’ I’m like, ‘No, dude, that’s in the textbooks. Now in the modern age I live in a house. I drive a car just like you do. I go to the supermarket if I want food.’”

Being Navajo didn’t keep Littleman from pitching for Arizona. And he got along fine with his teammates over four years. He’s injured now, but he hopes he can get his arm back in shape for an MLB tryout. In the meantime, he helps out at Naat’aanii, trying to pass on the things he learned there and in college ball. He says that having Indian stars in the major leagues lifts natives out of the past and into the present for mainstream America.

“You know, it’s almost like we’re like a lost race,” Littleman said. “We get that image of being non-existent. And when you’re on the stage where Chamberlain is or Jacoby Ellsbury, it gives them awareness that like we’re still here. It’s almost like we’re making a footprint in history, like opening their eyes, like these guys can play.”

The Future

In Farmington, 12 to 16 years old hopefuls take infield practice with Colorado’s snowcapped La Plata Mountains hulking in the distance. Matthew Duncan is a 13-year-old shortstop, big for his age, with a quick bat and a good throwing arm. He’s Navajo. He doesn’t speak the language, but his father does.

Duncan says he wants to play in the MLB and that he thinks it’s good for natives to play baseball.

“It will show that natives can do whatever the people can do, like, around the United States,” he explained.

Naat’aanii is no longer just for native players. Any kid can join if he has talent and desire. But the logo and rhythm and ethos are still Navajo. Dineh Benally wants his players to learn more than how to turn a double play. He wants them to tap into the tribal soul, to find the strength to stick it out when times get tough. Because they will get tough.

“That’s where they’ll show me if they’re really a true Naat’aanii,” he said. “If they’re gonna train and get up and work harder or if they’re going to lay around and quit. That’s why I tell them, ‘are you Naat’aanii?’ They look at me. They know what I’m talking about.”

Navajo kids have lots of sports to choose from today—basketball’s extremely popular. So’s football. And rodeo, though mostly on the rez. Those who choose baseball, at least at Naat’aanii, can reclaim a piece of their legacy on the diamond. And they can dream big, look up at the native players in the big leagues and say, “Why can’t that be me?”

This segment aired on March 22, 2014.