Advertisement

Can CTE Be Detected In The Living?

Monday Night Football is an American pastime, with its laser-like passes, speedy runners and bone-crushing hits.

“It's an organized collision with the same impact as a small car crash,” said Stacy Harvey, a former Arizona State University linebacker who spent a season with the Kansas City Chiefs.

Harvey's never officially been diagnosed with a concussion, but he says hard hits and numb fingers were part of the everyday life of a football player. Doctors don't have a treatment for the long term brain damage, known as CTE, that's been linked to concussions. But Harvey would like to know if he's at risk.

“At least if you know early, you know, you have a chance to make whatever decisions you need to make to put yourself in the best possible position for you and your family,” he said.

[sidebar title="OAG's Concussion Coverage" align="right"]For much of our 20-year history, Only A Game has reported on the issue of head injuries. Here’s a rundown of our in-depth coverage.[/sidebar]Enter a UCLA brain study of five former pro football players published last January in the American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. It claims to be the first to use a brain-imaging tool to find tau proteins in brains of living ex-players who suffered head injuries. Scientists think there may be a link between tau and long-term brain damage.

“This is preliminary data,” said Chicago Neurosurgeon Dr. Julian Bailes, who helped with the study. “We don't have a complete understanding of CTE, and we don't know for sure the impact of this test. It is, however, the only way that we know of that tau protein can be labeled and visualized in the human brain while someone is still alive.”

Bailes said the first phase of the study looked at former NFL players who had some sort of CTE symptoms: memory loss, personality changes, mild depression. Bailes said until this point, people with CTE had to die first before they could be diagnosed.

“If we couldn't diagnose any disease, say cancer, until after someone was dead, we really wouldn't have much of a chance to intervene and understand the disease, how it progresses, or help them,” Bailes said. “So the first step is to take something like CTE to a greater level of understanding and diagnosing it while people are alive.”

Advertisement

Bailes said the brain-scanning technology to look at tau seems to do that, at least in the preliminary study. Dan Flynn, the author of the book The War on Football: Saving America's Game, disagrees. Flynn claims the CTE study is rooted more in capitalism than science.

“The fact remains that there is no FDA approval of this product,” Flynn said. “There is no independent, peer-reviewed scholarship buttressing the idea that it works. All we have are the word of these doctors that we later find out are the owners of the company. That's incredibly shady.”

Bailes denies having a financial stake in TauMark, the company that developed the brain scan technology. But Flynn also questions the validity of the test.

“So if they find these protein deposits in your brain, does that mean you have CTE?” Flynn asked. “Well, everyone develops these protein deposits at some point, so I think what bothers me, not just about the test, but about the group studying CTE, is that we're at such a primitive stage that the two main groups studying CTE don't even agree upon the definition of what CTE is.”

While experts continue debating, there are some former players who'd rather not know. One player, who didn't want to talk on record, is concerned that being associated with a brain condition could jeopardize his current career. He worries that health insurance companies could hold a CTE scan against him.

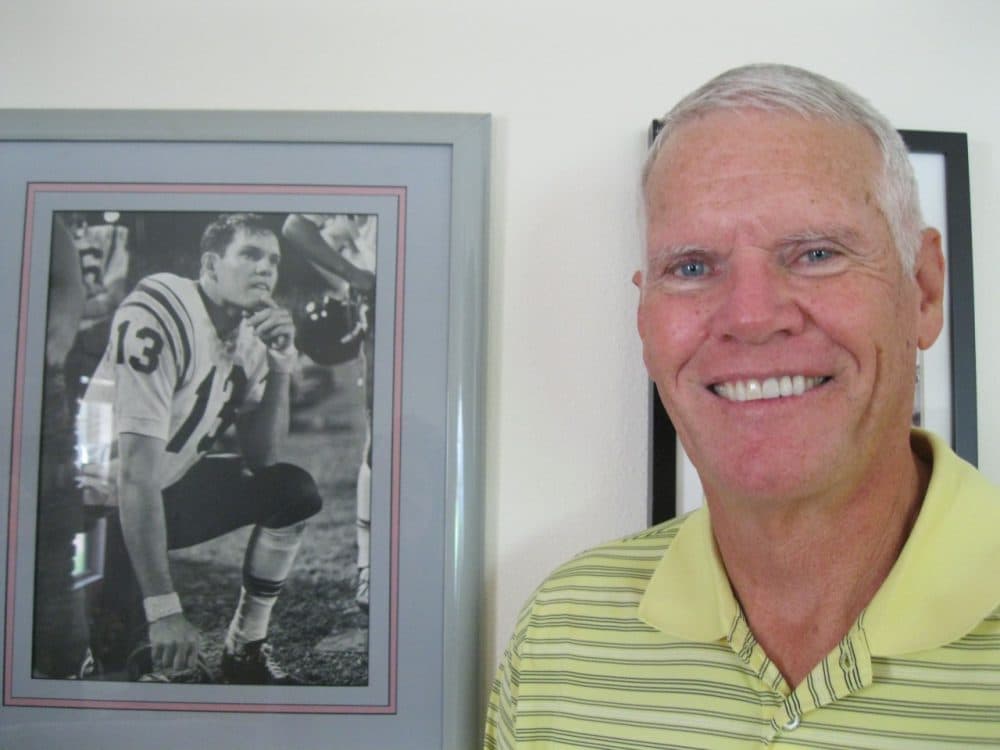

Retired NFL backup quarterback Wayne Clark didn't hesitate to be part of UCLA's CTE study.

Clark's own experience with the CTE scan surprised him. He suffered only one major concussion in 1972. Clark has never noticed any lingering symptoms. He said he'll occasionally blank on people's names. But what person in their late 60s hasn't done that?

“And I'm especially surprised because if you look at the scans that they have published, my scan shows as much or more tau in it as some of the other players who have significant issues,” Clark said. “And I don't know if that means I've got a ticking bomb or there's something about me — my genetics or my lifestyle or something — that has allowed me to not be impacted by those conditions.”

Clark has agreed to donate his brain so scientists can someday compare it to his CTE scan results. In a strange way, Clark says his results are an odd affirmation. He says as a backup quarterback, he often walked off the gridiron in a clean uniform.

“There were many, many times that I did it,” Clark said. “I didn't feel like I was a part of the team. I wasn't a part of the team effort. I didn't do anything to help. Surprisingly, one of the ideas that has struck me after this whole study is that this study and the results of it showing that I have tau in my brain kind of validated my career. And for me, it almost became my dirty uniform.”

Clark said it's going to take a cultural shift to take the damaging hits out of football. But he hopes if doctors can diagnose CTE in the living, then at least players will know the risks before they hit the field.

This segment aired on April 26, 2014.