Advertisement

The Rise, Fall And Rise Of The Rubik's Cube

When the Rubik’s Cube hit shelves worldwide in 1980, it immediately became popular. And when I say "popular," I mean, like, Pokemon popular. Harry Potter popular.

By 1981, sales were in the hundreds of millions, making it the best-selling toy in history.

"Back in my university days, back in the crazy cube times, you could sit in a lecture hall with 100 people and hear 10 or 15 cubes being discreetly turned around the room," Lars Petrus remembers.

"Were you one of those people playing with the cube in class?" I ask.

"Sometimes," Petrus says.

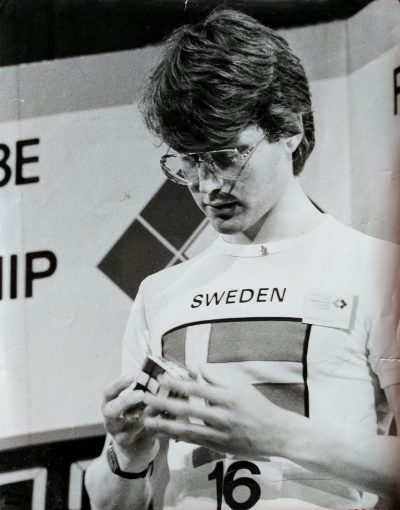

In 1981, Petrus became the fastest Rubik’s Cube solver in his native country of Sweden.

And as such, in 1982, he found himself at the first-ever Rubik's Cube world championship.

Petrus was 22 when he walked into the massive concert hall in Budapest, Hungary, birthplace of the cube.

"Were you nervous?" I ask.

"Of course!" Petrus says. "I think everybody was nervous."

Petrus solved his cube in 24.57 seconds.

But Minh Thai of the United States was even faster: just under 23 seconds.

Mr. Rubik himself handed Thai a gold-plated Rubik’s Cube.

Lost Among The Clutter

There was talk of holding another world championship the following year, in Los Angeles.

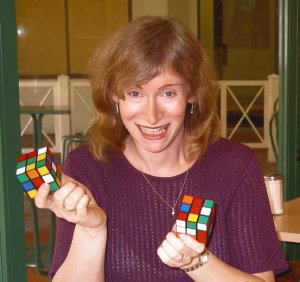

"But that never happened," says Jessica Fridrich.

Fridrich represented Czechoslovakia at the 1982 world championship; she was 17, and the only woman to compete.

As the 1980s wore on, the allure of the Rubik’s Cube wore off.

"What happened? Why were people not as crazy about it?" I ask.

"It’s just that it wasn’t popular," Fridrich says. "It wasn’t mainstream."

Maybe it was just too darn hard to solve. A Rubik’s Cube has more than 43-quintillion possible combinations; that’s 43 followed by 18 zeroes. It didn’t come with an instruction manual, and this was decades before you could Google instructions or watch a tutorial on YouTube.

So, people were getting frustrated. Some would take it apart and put it back together. Others, and yours truly may have been guilty of this one, would peel off and re-arrange the stickers.

Advertisement

Toward the end of 1982, Saturday Night Live captured the growing exasperation with its tongue-in-cheek ad for the "Rubik’s Grenade":

"Just scramble the colors, pull the pin, and then begin! Rubik’s Grenade: maybe the last puzzle you’ll never solve!"

So suddenly you had hundreds of millions of people shoving their cubes in the backs of closets and drawers.

But not Jessica Fridrich.

"Wherever I went, the cube went with me," Fridrich says.

It wasn’t just solving the cube that she loved, it was practicing hours a day to find quicker, more effective ways to do it.

"Nobody knew what the best system was," Fridrich says. "There were no computers that would just outsource this job. And this process of discovery and the unknown was what mesmerized me, what kept me cubing."

The Internet Revives The Cube

Over the course of a few years, Fridrich came up with a system for solving the cube. It involved memorizing at least 50 algorithms, or sets of movements, to get a piece of the cube where you want it to go.

More than a decade later, in 1997, Fridrich posted the method on a little something known as "the internet." Just for kicks.

"I thought no one was interested in cubing, no one would even just spend their time and memorize all the algorithms," Fridrich says.

She was wrong.

"People would search and they would find the page," Fridrich says. "They would learn the system. And it became extremely popular. I had no idea how popular it became until about 2000."

That’s because by the time 2000 rolled around, the world-wide web had given the Rubik’s Cube a jump-start.

"I mean, it’s a very simple thing. It weighs nothing. You don’t need a battery. It doesn’t break. You can have it forever. And now, pretty much anyone can learn it from the internet."

Lars Petrus

"I don’t think without internet I would still be cubing, because there was no one else to talk to," Ron van Bruchem says.

Ron van Bruchem fell in love with the cube in the 1980s, as a teenager in the Netherlands. When the fad died out, though, so did his interest.

"If there’s no one in your area who's cubing, then that's not much fun anymore," van Bruchem says.

Fast-forward two decades, and cubers were posting their solve times and email addresses online, thanks to a CD-ROM called Rubik’s Games. Then came a Yahoo group called "Speedsolving the Rubik’s Cube," inviting cubers to trade tips and techniques.

And in 2000, Ron van Bruchem started an online forum called speedcubing.com.

"Is it true that you invented the term, 'speedcubing'?" I ask.

"Well, what’s funny is that I got contacted by Webster — that they were planning to include the word in the dictionary, and that they attributed the word to me," van Bruchem says. "So that was really nice."

Just to give you an idea of how cube-obsessed Ron van Bruchem is: his wedding was Rubik’s Cube themed, replete with a six-colored cube cake that took four days to make. Plus, he now has more than 1,000 cubes in his house.

"Even in the bathroom and in the shower," van Bruchem says.

"Are cubes waterproof?" I ask.

"Well, I have specific cubes that I save for water-solves, yeah," he says.

The Cube Craze Takes Shape

Anyway, after starting speedcubing.com in 2000, Van Bruchem became a leading voice in the growing online cubing community. Before long, talk turned to picking up where the 1982 Rubik’s Cube world championship left off.

"I said, 'We should have a competition,'" van Bruchem recalls. "'I would love to meet you guys, somewhere, someplace.'"

Van Bruchem connected with a Canadian cuber named Dan Gosbee, who offered to take the lead.

And in 2003, nearly 100 cubers descended on Toronto.

"It was, for us, a really big reunion," van Bruchem says. "And it brought the people together, and that’s what it was all about."

This was the first world championship since 1982. But here’s the thing. It drew five times more contestants. And there were far more categories of competition. Beyond solving the traditional 3-by-3 cube, you could do the 4-by-4, the 5-by-5, dodecahedron and tetrahedron puzzles. You could even solve blindfolded! So there wasn’t an established precedent for how things should go. As a result?

"There was a lot of misunderstanding and also some unfair decisions that were made just because we didn’t know the exact rules," van Bruchem says.

For instance:

"We never really set a time limit," van Bruchem says. "So there was one competitor who couldn’t even solve the cube. And he even took, like, one hour and then finally we decided, well, come on, you can’t even solve it if you can’t do it in one hour. So we had to stop him."

After the event, some cubers voiced their disappointment online, and organizer Dan Gosbee took it hard. Seems he still does: he turned down my request for an interview, saying he didn’t "want to relive the experience."

But the willy-nilly nature of the 2003 world championship actually had a silver lining. It turned competitive speedcubing into an organized sport when Ron van Bruchem co-founded the World Cube Association.

The WCA wrote up detailed regulations: everything from how a competition area must be lit…to how far away spectators have to stand while someone is solving the Rubik’s Cube.

The Rubik's Cube Gets A Makeover

Now, at this point I should clarify something. When we’re talking about competitive speedcubing and we say "Rubik’s Cube," we’re not actually talking about the Rubik’s Cube. Because since the mid-2000s...

"The old '80s Rubik’s Cube has been mostly phased out," says Chris Tran, a cube solver and cube-innovator.

Tran's company, The Cubicle, engineers "speedcubes": they look like Rubik’s Cubes, but on the inside they have high-tech features, like magnets, that make them smoother, faster.

"These new Rubik’s Cubes have special features that hold themselves in so you can turn them about like 100 miles per hour and the pieces won’t go flying," Tran says.

"Wait, wait – you said 100 miles an hour?" I ask.

"Oh! It’s a little bit of an exaggeration," Tran says. "But a lot of these kids, they turn about four to nine moves a second."

It’s true. As cubing has taken off, solve times have dropped.

Remember in 1982, when Minh Thai wowed the world by conquering the cube in under 23 seconds? Well, by 2009, world champion Breandan Vallance was solving it in under 10.

And in 2016 Feliks Zemdegs solved it in under five. That’s half the time it takes Usain Bolt to run the 100-meter dash.

These days, roughly 20,000 people compete in cubing events around the world. The World Cube Association holds nearly 700 competitions a year… from Guatemala to Algeria to Mongolia. Just like in Jessica Fridrich’s day, most of these cubers are male, though the number of females is growing, slowly.

But whether they’re guys or girls, the majority of today’s cubers are, like Chris Tran said, "kids": teenagers, if not younger. In this digital age, a new generation is getting hooked on this old-school, analogue toy.

Lars Petrus, the guy who represented Sweden in the 1982 world championship, thinks he knows why.

"I mean, it’s a very simple thing," Petrus says. "It weighs nothing. You don’t need a battery. It doesn’t break. You can have it forever. And now, pretty much anyone can learn it from the internet.

"And it’s a lot more rewarding when you can actually finish the puzzle," he says with a laugh.

To quote the man who started this whole thing, Mr. Erno Rubik:

"If you are curious, you’ll find the puzzles around you. If you are determined, you will solve them."

This segment aired on July 15, 2017.