Advertisement

'We Just Wanna Be A Part Of It': The Women Who Fought To Cover MLB

Resume

When I meet veteran baseball writers Lisa Saxon and Melissa Ludtke, they’re sharing a rented house in Cooperstown, New York, right near the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

These lifelong baseball fans have journeyed to Cooperstown to celebrate a milestone in the world of sportswriting.

"I can’t believe I lived to see this day, given what we all went through," Lisa says.

"No, I mean, it’s absolutely a moment I never would have imagined possible back in the '70s — it wouldn’t have even occurred to me," Melissa says. "I mean, here we were, you know, fighting Major League Baseball in court for what we thought was just so obvious, that we were here, saying, 'We just love your game. We just wanna be a part of it. We just wanna cover it.'"

The Call

Melissa’s "fight" began in 1977.

She was in her 20s, a hungry young researcher and reporter for Sports Illustrated. She was one of the only women writing about baseball at the time, for any news outlet. She’d been assigned to cover the 1977 World Series between the New York Yankees and the Los Angeles Dodgers.

But even though both teams had granted her access to the field, and the locker room, during the first game she got a call that would change everything.

"The commissioner’s office called me and said, 'No go. We’re in charge of the clubhouses. I don’t care what the Yankees say, we don’t care what the Dodgers say,’" Melissa remembers. "I said, 'Why are you making this decision?' He said, ‘Well, we haven’t polled the players’ wives,' to which I said, 'What have you ever polled the players’ wives about in terms of baseball policy?' And he said, also, he said, 'If we were to allow this to happen, the players’ children would be ridiculed in their classrooms the next day.' Those were the two reasons given to me why my right, which was on the clubhouse pass given to me, was taken away.

"And, I mean, it was just — the clubhouse is more than just the quotes you get. It’s the sensation. It’s what you hear, it’s what you see, it’s sort of the tenor, it’s the tone, it’s what you pick up. It’s what any good reporter just wants to be part of. And, that was gone. That was absolutely gone."

Melissa and her employer, Time Inc., sued Major League Baseball for violating Melissa’s right to equal protection under the 14th Amendment. In September 1978, they won that case, with the judge ruling that whatever locker room policy Major League Baseball came up with, it had to be equal for male and female sports reporters.

But the commissioner of baseball? Bowie Kuhn? He just couldn’t let that decision go.

So, the 1978 World Series rolled around, and it was time for his office to set the media policy for locker rooms.

"And so he went back to the judge and asked if he really could set whatever policy they wanted and the judge said, 'As long as it’s equal,'" Melissa says. "And so the very first night he made this decision that there would be a period of time where all the reporters would go into the locker room, and then they would clear the locker room of all the reporters."

The players would have ten minutes to get dressed, and all the reporters would go back into the locker room.

"This would be equal," Melissa says.

But this new policy caused an uproar.

"Well, I recall that night vividly, because as they began to clear reporters out, the men started protesting," Melissa continues. "They couldn’t understand how they could be treated this way, that they were being restricted in their time in the locker room. And, you know, I didn’t make one comment that night. But I watched it with the thought in my head that, you know, for the first time you’re understanding what our struggle, our battle, our fight, our lawsuit, you know, is about. And, I will tell you: That policy lasted one night."

'Token Female'

The next season, Lisa Saxon came on the scene as a sports reporter with the LA Daily News – though in those days, she was writing under her maiden name, Nehus.

"The day I arrived to work — this was just the tell-tale sign for me — my very first day, I arrived to my desk and they had made a sign for me and it said 'Token Female,'" she says.

That moment inspired Lisa to work even harder. She meticulously kept track of every single stat. And even though her salary was peanuts compared with the guys, she put in longer hours than anyone.

So fast forward to 1982. Melissa had moved on to covering other sports, and Lisa now had the California Angels beat. The Angels’ manager was Gene Mauch.

"I stuck my hand out and I said, 'Hi, Gene. Lisa Nehus. It’s nice to meet you. I’m gonna be with the team for the rest of the season.' He let my hand hang in the air. He crossed his arms and he said, 'You can come into my locker room, but if you come into my office, I’m not talking to anyone.' He turned on his heels and ran behind second base to watch batting practice. And I waved at him, and I said, 'Hi, Gene. Nice to meet you, too.'"

And Gene Mauch made good on this, what, promise? Threat? If Lisa tried to come into his office for postgame interviews, he wouldn’t let anyone in.

"So I used to have to wait outside the manager’s office, because the protocol after the game is first you talk to the manager, then you talk to the players," Lisa says. "That left me in the locker room alone with the players."

And that’s no small thing. See, even though Melissa Ludtke’s lawsuit let women reporters inside the locker room, it couldn’t control what happened once they got there.

"Going in the locker room, knots would get in my stomach," Lisa says. "It actually is a physically uncomfortable thing to do because you didn’t know what you would face. And at the very least you would have jockstraps thrown at you and dirty undergarments. And that was an everyday occurrence, and then you would just build onto that what might happen. And you just hoped for the best when you went in."

This, Lisa says, this is where she found her true angels — among the California Angels.

"While the guys were in talking to the manager, I could go stand by Rod Carew’s locker, with Ron Jackson, Papa Jack, and they were in a corner of the clubhouse where I couldn’t see anything," she says. "And I could just talk to them until the other writers came out, or the player I was waiting for was dressed. And I could say, ‘I need to talk to this person or that person, can you let me know when it’s a good time to go over?' And those guys helped."

Then came the 1983 season. Gene Mauch had been replaced by John McNamara, who’d been hired away from the Cincinnati Reds.

"I have to be honest with you," Lisa says. "I remember one night, we went in for the postgame meeting, and the first question to him is, 'Why did you leave Andy Hassler in there?' Hassler had given up a home run. And McNamara threw the food off his desk and he said, 'All of you, get out of here. Except you.' And he’s pointing to me, and I’m like, 'Oh, my God, what?'

"And so I stayed and I said, 'Yes, what do you need?' And he said, 'What question was asked to me, Lisa?' And I said, 'Why did you leave Hassler in?' He said, 'I’m going to tell you how to ask that question: What factors led to you deciding to leave Hassler in? Now, you tell me the difference between the two questions.' I said, 'Well, one, I’m acknowledging that you had a reason for doing this.' And he said, 'Absolutely. And if you want to survive in baseball, this is how you’re going to ask questions.' And he said, 'Now, ask the question.' I did. And he said, 'You’re the only one getting this answer tonight.'"

This Close To Quitting

But even with Angels manager John McNamara on her side, 1983 was a tough year for Lisa. Players continued to verbally and sexually harass her. Other writers spread rumors about her sleeping with players. During a road trip to St. Louis, a security guard tried kicking her out of a hotel, accusing her of being a sex worker. By the end of the season, Lisa was this close to quitting her job. And she told John McNamara as much.

"And he stayed up with me until 5 o’clock in the morning, talking with me," Lisa recalls. "And he said, 'I want you to clearly articulate why you’re not coming back.' And I said, 'It’s so hard. I face A, B, C.' And he said, 'You still haven’t given me a reason, because none of them have to do with you; they have to do with other people. Until you can give me a reason why Lisa shouldn’t cover baseball, I fully expect to see you back here next year.'"

And, he did. Though now, Lisa was covering the LA Dodgers. It was 1984, and at this point, although every clubhouse in the American League was officially open to women, some teams in the National League wouldn’t let them in.

But, in spite of everything, what Lisa was determined not to do, was complain.

"'Cause if I complain, they’re going to pull me off or use it as a reason to pull me off," she says. "And that’s when I came up with my pat lines."

When a clubhouse attendant turned her away, she’d fire back:

"I have a Baseball Writers' Association of America pass that says I should be let into the locker room. And this says 'Admit Bearer,' not 'Admit Bearer With Penis.' Are you going to do penis checks on everyone? Because if you do, you’re gonna find out I really have big balls."

By the end of the 1984 season, Lisa Saxon was exhausted. From the start of spring training to the end of the season, she’d only taken two days off.

And it wasn’t as if she had this huge support network of other female sportswriters to turn to. In the mid-'80s, she was one of just three women covering the majors full time. There was her friend, Claire Smith, who reported on the New York Yankees for the Hartford Courant. And Susan Fornoff, who wrote about the Oakland A's for the Sacramento Bee.

But that was it.

'You Are The Best Writer On This Beat'

Still, Lisa Saxon was determined to keep on keeping on. But remember Gene Mauch? The manager who ran away from Lisa when she introduced herself? The one who told her that if she tried interviewing him in his office, he wouldn’t let anyone else in?

Well, in 1985, Gene Mauch came back to the Angels.

"So I’m thinking, 'Oh, God, please help me,'" Lisa says.

"And so one day I was talking to Gene, and he said, 'I just want you to know, I respect the hell out of you. You are the best writer on this beat. There is no one who knows more about baseball.'

"But when I look at you, I see my daughter. And when I see what happens to you in that locker room, I think of my daughter.' And I said, 'Well, Gene, I want you to turn your thinking around. If you want to think of your daughter, that’s beautiful. But change the script of her life. Your daughter wants nothing more than to be a baseball writer.'"

Gene Mauch told Lisa that he still didn’t like seeing her in his locker room, but he allowed her into his office.

"That was my moment where I knew I’d been accepted, if I could win over Gene Mauch," she says.

By 1988, Lisa moved on to covering the LA Raiders, and college sports. In 1989, she found herself having trouble concentrating; a doctor diagnosed her with "combat fatigue."

Lisa says she carried around a lot of hurt after her years in baseball. She had her share of high points — like that moment with Gene Mauch — and her share of angels and allies. But by the time she left sportswriting to teach journalism in 2001, she had a lot of healing to do.

Since then, sportswriters — male sportswriters — have been getting in touch to apologize for not having done more to support her. And these conversations mean the world to her.

The Highest Honor In Baseball Writing

But what happened in Cooperstown this summer means the universe. See, there’s a pretty big reason Lisa Saxon and Melissa Ludtke came in from LA and Boston, respectively, and rented a house, along with several female sportswriters working in the industry today.

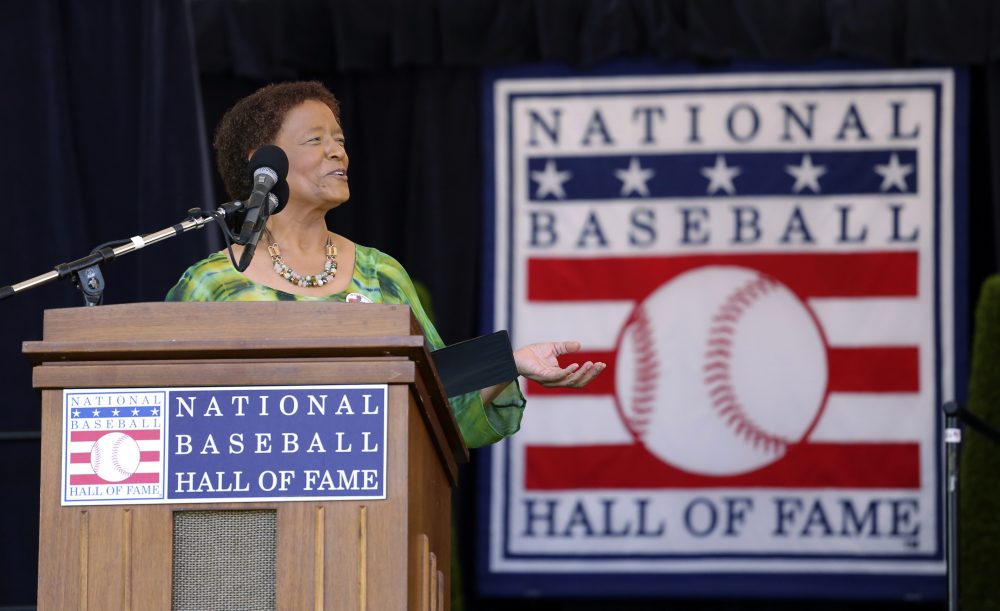

You see, during Hall of Fame weekend, when the National Baseball Hall of Fame held its annual induction ceremony, for the first time, a woman received the highest honor the Baseball Writers' Association of America bestows: the J.G. Taylor Spink Award.

The recipient was Claire Smith, one of Lisa Saxon’s few female compatriots from the 1980s. When Claire took over the Yankees beat for the Hartford Courant, she was the first woman to cover a major league team full-time. She also wrote for the New York Times and the Philadelphia Inquirer. Now she’s an editor with ESPN.

"Today, I humbly stand on this stage on behalf of every single person in my profession in baseball and beyond who was stung by racism or sexism or any other insidious bias, but persevered," Smith says in her acceptance speech. "You are unbreakable. You make me proud."

This segment aired on September 2, 2017.