Advertisement

The U.S.-Canada Alliance — And Hockey Program — Born From An Explosion

In 1911, the U.S. Speaker of the House, a guy named Champ Clark, took the floor and said:

"I look forward to the time when the American flag will fly over every square foot of British North America up to the North Pole."

"The speaker of the house, the Paul Ryan of his day, actively advocates for the annexation of Canada. That's his whole point," author John U. Bacon explains. "He received loud cheers and a great write-up in the Washington Post. So that's how unfriendly we were as late as 1911."

(Spoiler: The U.S. obviously did not try to annex Canada. Sometimes you just have to realize the speaker of the house has a bad idea, you know?)

But meanwhile, north of the border, lots of people were not too fond of the U.S.

Joseph Ernest Barss, the guy at the center of this story, was 19 years old in 1911 — and he had basically been born to hate the United States. It was in his blood.

His ancestors had once lived in Massachusetts, but fled to Nova Scotia as tensions rose between the colonists and England.

"They were loyal to the Crown and not to the rebels — the revolutionaries, of course," Bacon says.

When the Revolutionary War started, Barss’ great-great-grandfather fought on the British side.

But Barss was named after his great-grandfather, who was even more fearsome.

"He captures, burns or sinks more than 60 American ships during the War of 1812," Bacon says. "He becomes the most wanted man in America. And that is our hero's great-grandfather."

Advertisement

A Personal Reason To Hate The U.S.

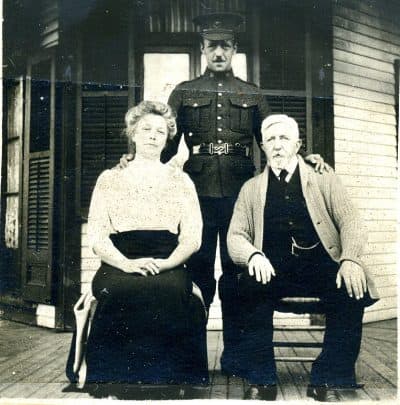

Joseph Barss grew up in Wolfville, Nova Scotia. He was just 5-foot-8, but he was strong. He starred on the hockey team at Acadia University.

Not long after graduation, he found a personal reason to hate the United States.

In 1915, he gave up a comfortable job in Montreal to join the Canadian army in the trenches of World War I. He was angry that the United States wasn't yet sending troops.

Soon, he had bigger problems.

At the Battle of Mont Sorrel in 1916, a German trench mortar nearly killed him. Barss was in a body cast for six months, then returned to Wolfville — about an hour from Halifax — to recuperate. The man who'd once been strong enough to do a lap around the rink on unlaced ice skates now struggled to move his left foot.

"He comes back and he's kind of a lost soul, essentially," Bacon says. "He does not want to go back to Montreal and be a businessman. He does not want to take over his dad's grocery store, which his dad thought he would. So he's lost, looking for a sense of purpose — and he finds it by accident."

'That's How Terrified They Are Of This Thing Blowing Up'

In November 1917, Russia dropped out of the war. This meant the Germans could focus on the Western Front — and that made the Allies very nervous. They decided they needed more firepower.

A French freighter called the Mont Blanc went to New York to stock up on airplane fuel and explosives. Then it headed north to meet a convoy in Halifax that would then leave for Europe.

The Mont Blanc was packed with six million pounds of TNT and another explosive called picric acid.

"That is 13 times the weight of the Statue of Liberty," Bacon says. "And they’re so nervous about it that they cover their boots with canvas covers to make sure they don't spark on deck. You're not allowed to have matches on your person anywhere near the ship. And in a smoking era, that's a four-day sacrifice these French guys are not used to. So that's how terrified they are of this thing blowing up, and it crawls up the coast to Halifax."

German U-boats had already sunk 3,000 Allied ships, so the Mont Blanc crew was itching to get into Halifax Harbor.

"These guys are terrified of getting blown up," Bacon says. "Another ship, the Imo, a Norwegian supply ship, it's already a day late and wants to get to New York to load up with various relief supplies. They have no idea what Mont Blanc has got on it. Only, like, five guys in the harbor who aren't on the ship know about this.

"Imo is in a hurry that morning and it keeps on passing ships on the left — that is against nautical convention."

Both the Mont Blanc and the Imo reached the narrows of Halifax Harbor at the same time — heading right at each other.

"And Mont Blanc thinks this guy is crazy and has one blast on the horn, which means, 'I'm in the right place. You need to move,' " Bacon says. "And Imo comes back with two blasts saying, 'Screw you. I'm gong this way.' Finally, at the last second, Mont Blanc realizes this guy's crazy, so it bails to the left to the middle of the harbor, just as Imo does the same thing."

They collided. It wasn't a big collision, but it was enough to knock over barrels of airplane fuel on the Mont Blanc.

"And the stuff ignites," Bacon says. "And the crew knows they're about to blow up. So they hop on their row boats and go the other way, away from Halifax, crucially. Instead of warning anybody, they go to the woods of Dartmouth and run into the woods as far as they can."

The ghost ship, now on fire, continued toward pier six in Halifax Harbor.

On land, one of the guys who knew what the Mont Blanc was carrying started hollering that the ship was gonna blow, and everyone needed to run.

A train dispatcher named Vincent Coleman heard the message and started to run for his life.

"And then he stops," Bacon says. "Because he remembers that the No. 10 train from New Brunswick is coming in in five minutes. It's gonna park right in front of pier six. And if it does, everyone's gonna die. So he runs back to the telegram office. And starts furiously clacking off these messages to other train stations, saying the following, 'Hold up the train. Ammunition ship afire in harbor making for pier six and will explode. Guess this will be my last message. Goodbye, boys.' And those were his last words."

Aid From Barss — And Boston

At 9:04 in the morning, the Mont Blanc exploded.

"This is a miniature atomic bomb," Bacon says. "Human beings were blown half a mile in all directions. In that split second, 25,000 people are homeless. Half the city is gone. Nine thousand are wounded, and 2,000 are dead."

For the next 3 and a half hours, all the telegraph lines in Halifax were down.

But thanks to that final message from Vincent Coleman, word started to spread.

And that's how Joseph Barss and the people in Wolfville got the news.

"A doctor friend of his says, 'You know first aid. You gotta come and help me,' " Bacon says.

Barss, still walking with a cane, boarded the next train for Halifax and ended up at Camp Hill hospital. The hospital was packed. There were so many people in need of help that doctors ran out of anesthesia. They kept operating.

For the next 14 straight hours, Barss dressed wounds, set fractures and even helped with surgeries — something he'd never done before.

Vincent Coleman's message had also gotten to Boston. The Massachusetts governor called an emergency meeting and, without waiting to hear back from anyone in Halifax, decided to send a train filled with doctors, nurses and medical supplies.

Meanwhile, Barss kept working in the hospital.

After about three days, he was finally relieved by the doctors from Boston.

Nova Scotia historian Thomas Raddall wrote, “substantial help was on the way from Montreal and Toronto, but the first and most valuable assistance came from that ancient foe beyond the Bay of Fundy.”

"And that is when the U.S. and Canadian relationship starts to change, and very dramatically," Bacon says. "And Barss himself, very anti-American for a lot of reasons, he says, 'I will never be able to say enough about the wonderful help the States have sent. The response was so spontaneous and everything done even before it was asked for. It brought tears to all of our eyes. You know we've always been a trifle contemptuous of the United States on account of their prolonged delay in entering the war. But never again. They can have anything I've got. I don't think I feel any differently than anyone else down here, either.' "

The Birth Of Michigan Hockey

On the train ride back to Wolfville, Barss, the man who'd been so lost, realized what he wanted to do with his life: he would become a doctor.

Instead of going to a Canadian university, Barss enrolled at the University of Michigan.

There, he started to skate at Michigan's Coliseum. This was the steel and concrete, three-walled building that housed the hockey rink. Barss slowly made his way around the ice, trying to regain control of his foot.

By 1922, he was healthy enough to referee the club hockey team's games.

"And finally he walks down to the athletic director's office — Fielding Yost, who built the Big House in Ann Arbor, one of the most legendary coaches out there. And Barss says, 'You need a hockey program,' " Bacon says. "Yost is from West Virginia and born in 1871, the son of a Confederate solider, so this guy does not know a damn thing about hockey. Rest assured. But he saw something in Barss that he must have liked, and Fielding Yost says, 'Only if you're the first coach.' And he gives him the full reign and the funding for it. So that is how the University of Michigan got hockey."

One Giant Thank-You

For the next five years, Barss shuttled between his med school classes and the hockey rink. He coached Michigan to two league titles. The team was popular. And that early success mattered. During the Great Depression and World War II, many schools in the Midwest dropped their hockey programs. But not Michigan. The Wolverines have since gone on to win nine national championships — more than any other program in the country.

And Boston and Halifax have stayed connected. Every year, Nova Scotia sends a 50-foot, 2-ton Christmas tree to Boston as thanks for the city’s help after the explosion.

As for Joseph Barss, after finishing medical school, he became the chief of surgery at a veterans hospital in Chicago, then opened his own practice.

Oh, and one last thing. Joseph Barss, great-grandson of the guy who sank all those American ships, wound up marrying a woman from Battle Creek, Michigan. He became an American citizen.

Reach much more about the life of Joseph Barss and the events of Dec. 6, 1917 in John U. Bacon's book, "The Great Halifax Explosion: A World War I Story of Treachery, Tragedy and Extraordinary Heroism."

This segment aired on December 7, 2017.