Advertisement

Sin And Baseball: A Confession

Resume

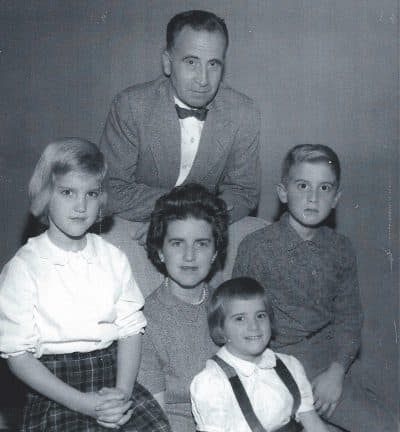

My father was a Christian Brethren, my mother a Presbyterian, and while I was growing up, I was dimly aware that they’d worked out a deal. On Sunday mornings, my mother, in her pearls, heels and modestly stylish dresses, would take my two younger sisters and me to the Presbyterian Church in my hometown of Basking Ridge, New Jersey.

Then, collecting my father, we’d all squeeze into our rattly 1959 Ford Ranch Wagon. A half-hour later, at 915 Grant Avenue in Plainfield, my father’s aging mother would be waiting for us, tapping her cane in the doorway of the old house where she’d lived for 50 years.

Here we entered a different world. Dark, olive-colored drapes. Dark rugs. Everywhere a faint mothball smell. All was still. All was quiet, except for the slow ticking of the grandfather clock in the hallway, a clock about the size a coffin. Death was always on my grandmother’s mind. As was sin. "Sin," she said, "is breaking the law of God, especially the Ten Commandments.”

The stickiest wicket was keeping the Sabbath. In my grandmother’s house, the Sabbath was "kept holy" all day, a day for "spiritual rejuvenation." So no Parcheesi or Monopoly. No TV. No radio. As my mother, in an armchair, knitted in a kind of quiet fury, my father, a mild-spoken businessman who honored his mother, would listen and nod while my grandmother read from her small black book of the Gospels.

I’m afraid that little of this felt rejuvenating to me — and not only because I lacked interest in the subject matter, but because I’d become very interested in another matter that would complicate the Sabbath. On a sunny Saturday in the previous summer of 1960, my maternal grandfather, a silver-haired Presbyterian in a straw hat, had picked me up and driven me to a Yankees game in the Bronx. It was an innocent act of generosity and family fellowship, but unbeknownst to him or me, it started me down that darkening path toward perdition.

The game was glorious. We booed and cheered, my grandfather and I. I was a short, thin 7-year-old kid with a limp, but from that day until the end of his days, he called me "Mantle," the Yankees’ incredibly swift, strong home-run hitter, the hero of the team. And from then on I was in love — there is no other word for it — with him and the Yankees. As a Presbyterian, he had no problem with listening to or even attending Sunday afternoon games. "Dear Mantle," his letters always began. “Did you hear the game on Sunday?”

Well, I’d heard about it.

For the rest of that season — except on Sundays — I listened to Yankee games with my ear glued to my parents' big Philco radio in the kitchen. Then, on the following Christmas, my father gave me a white, button-down shirt, and my mother gave me an AM transistor radio. I couldn’t walk or sit or practically breathe without my fingers around my Lafayette, model FS-91 "Mighty 9" transistor. After school, I listened to DJ Jack Carney, and when I was allowed to stay up late on Friday nights, I’d hear Scott "Scottso" Muni spinning hits like "Shop Around," "Good Time Baby" and "I’m in the Mood for Love," all of which had an obscure and uncomfortable allure.

Then in early April, at the beginning of the 1961 baseball season, it came to me like a whisper that was quieter but more powerful than the allure of those top-40 hits:

What if I just happen to have my radio in my pocket when we go to Grandmother’s house? And what if, when we’re there, I figure out how to listen to games without anyone knowing?

"It was an innocent act of generosity and family fellowship, but unbeknownst to him or me, it started me down the darkening path toward perdition."

William Loizeaux

So on a Sunday in mid-April, I slid my radio into the inside pocket of my jacket. Now and then as we traveled to Plainfield, I lightly touched that pocket in the nervous and reassuring way that Catholic girls touched their rosary beads. As my grandmother would have warned, this is how sin works. It worms into your tiniest crevices, grows, overtakes you, then cracks you open.

I slumped on the sofa and grimaced as in pain.

"What’s wrong?" my grandmother asked, frowning and looking up from her little black book.

"You aren’t going to get sick, are you?" my father said, suddenly energized.

"Oh, for heaven’s sake!" my grandmother said.

"He’s going to throw up!" my sisters cried, bolting up from the sofa.

"No, I don’t think so," my mother said calmly. She set her knitting aside, came over and put the back of her wrist against my forehead. "I think you’re OK, but maybe you should go upstairs and take a rest."

This sounded reasonable to everyone. I climbed the stairs to the second-floor guest bedroom.

It was another dark, green room, more the color of pine trees than olives. I slid the Mighty 9 out of my jacket pocket, and suddenly I was feeling sick.

What if I get caught — caught breaking the Sabbath?

Then, slowly settling my stomach, there came a soft, smooth, sliding feeling that I couldn’t and didn’t want to stop.

I can do this. I can get away with it.

I held the radio in the cup of my hands. With the volume low, I slipped it under the pillow to muffle the sound, and with a keen and guilty pleasure, I closed my eyes. Listening to every word, I drifted away from that room, that house and my grandmother reading downstairs. I heard the crowd. I smelled the popcorn …

The doorknob turned slowly, and in the shaft of light that came in the room, I saw in silhouette my mother’s head with her thin neck and wavy hair.

“How are things going?”

“Better,” I said.

She cocked her head as if she’d heard something, but she didn’t come in the room. Then she whispered, “Are we winning?”

I lifted my head and nodded.

“Well, let’s keep it that way.”

The shaft of light narrowed as she closed the door.

This breaking the Sabbath continued all through the 1961 season, when Yankees pitcher Whitey Ford won 25 games and didn’t lose one on a Sunday. Most memorably, it was the season when Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris chased Babe Ruth’s record of 60 home runs. As it happened, Mantle hit a home run on the Yankees’ first Sunday game of that year. On the last, October 1, Maris hit his record-breaking 61st — and I heard it, Phil Rizzuto making the call:

"Here's the windup, fastball, hit deep to right, this could be it! Way back there! Holy cow!"

Never has the Sabbath been so deliciously violated, so gloriously unholy, so unkept. My grandmother was right. Given a toehold, sin engulfed me. It cleaved me, and cloven I became what I’ve been ever since: that kid who went to church on Sunday mornings and the kid who listened to his Lafayette Mighty 9 in that guest room on those Sunday afternoons, when I sinned with all my heart and soul.

This segment aired on June 16, 2018.