Advertisement

The Judo Tournaments That Brought LA Kids To A Japanese Internment Camp

The judo dojo at Manzanar isn't easy to find.

Next to an old poplar tree, amid dead desert shrubs and green sage brush, are rocks that outline where the dojo used to be. And it's here where one of Manzanar's most fascinating sports stories took place during a war time filled with anti-Japanese hysteria.

Richard See was a kid in Los Angeles back then.

"My grandfather was Chinese," See says. "My father was half Chinese. My mother was white. None of us looked Asian, except my grandfather."

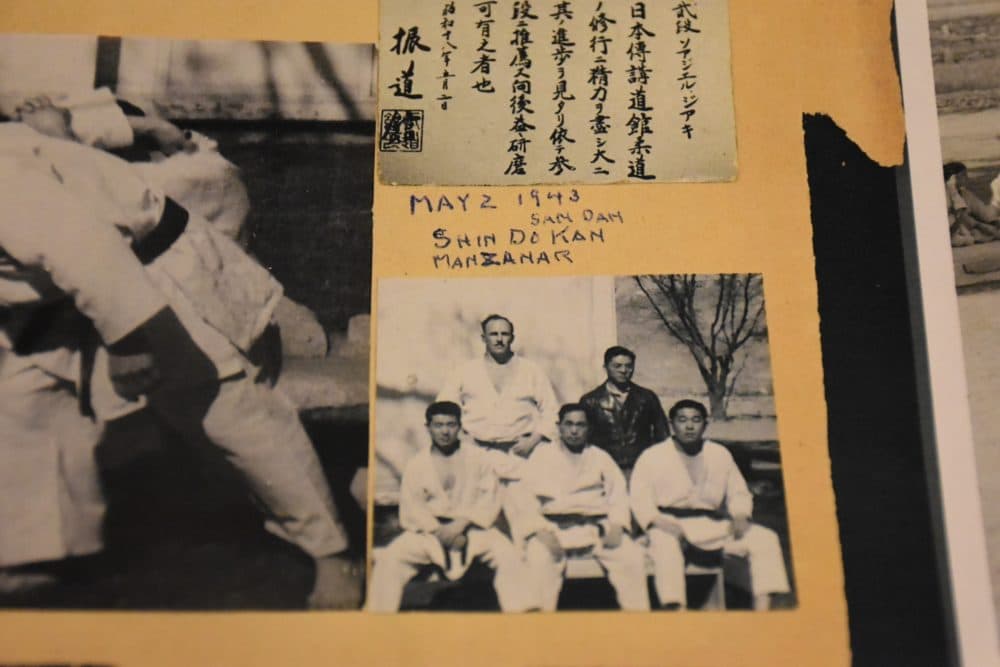

I found See through an old photo from the dojo. It shows a group of 10 people wearing judo suits, posing in front of that poplar tree. Their names are handwritten across their chests. See is in the front row, kneeling. He's the only one in the photo still alive. He's now 88.

"Well, at the time we were living in the house of a Japanese family that had evacuated," See says. "But they had a space underneath the house where they had stored a lot of stuff — not just of their own, but of other people."

For his birthday one year, See and his family flew a Japanese wind sock — the kind that’s shaped like a fish.

"And somebody across the valley reported us to the FBI," See says. "Because they said that we were flying a Japanese flag. And so the FBI came and talked to my dad, and it was no big deal."

Shortly after the war started, See's uncle Ted, who was only about two and a half years older than him, started taking judo lessons.

"Some of our favorite movies when we were kids were the Mr. Moto movies," See says. "They were about a supposedly Japanese detective, played by Peter Lorre. And he knew judo. And Ted wanted to be able to learn how to do all that — you know, throw people around and stuff. And I sort of went with him."

See and his uncle took lessons from Jack Sergel, an LAPD sergeant who’d become the sensei of a nearby dojo after all of the Japanese senseis were forced to leave. Sergel had friends interned in Manzanar.

Advertisement

"The only people who could, at that time, award a promotion — from a white belt to a brown belt or brown belt, one of those degrees — was a person who had received their training in Japan or by Japanese," See says. "And that's what we went up to Manzanar for. Because there was a tournament."

Clyde Tichenor was also in the group. He recounted the experience in an oral history interview that's part of the Manzanar National Historic Site Collection.

"It was just a matter of if you could scrounge up the gas to take you there, since it was rationed at that time," Tichenor said.

Tichenor said the Manzanar dojo had open sides all around. The internees had a special name for it.

"Shindo Kan," Tichenor said. "They called it that themselves. And it was a joke because the building was so rickety, it quaked and shaked. And shindo means ‘shaking and quaking.’ "

Tichenor, See and the others would compete in matches to determine who would earn a promotion to a higher rank.

"It was a contest," Tichenor said. "And the people who watched it were just the people who lived here — and plus what Caucasians were with us. There were probably 20 to 50 people milling around outside the open sides. Of course, they all knew that we were visiting as a Caucasian group. And this was kind of interesting to them, I'm sure. And they wanted to take a look at us to see if we looked like normal Caucasians, I guess."

Richard See was young enough that he only remembers random things about that Manzanar tournament. It was his first trip away from home. He got to stay in a hotel and eat steak dinner in town, which was a rare treat during the war. And he could actually see the stars, something he'd never experienced in Los Angeles.

"I ... at the time, I didn't really think of it as a concentration camp, exactly, you know?" See says. "But that's what it was. And so I didn't. It was just ... I don't know. I don't know. Maybe because I was so young.

"It all seemed pretty much — I mean, it was strange because I was away from home. But the camp was just one of the strange things.

"It was hot, and it was, I think, at a higher altitude than most of us were used to — certainly what I was used to. And I got winded really quick. And I won the first one and pulled a draw on the second one. So I didn't get a promotion."

Clyde Tichenor did earn a promotion. But he said that wasn’t the only thing he took away from the tournament.

They were, of course, happy to see there were some Americans that weren't prejudiced against them.

Clyde Tichenor

"They treated us very normally," Tichenor said. "The same as we treated them. But they were, of course, happy to see there were some Americans that weren't prejudiced against them. And to us it was — there were the Japanese who were nationals from Japan who made a war against us. And then there were these other Japanese people that had lived in the — particularly Los Angeles — area who, by presidential edict, got moved out for a while. We didn't see why, because Japan had decided to be warlike, it had anything to do with them."

But the Hearst newspapers in Los Angeles didn't see it that way. Sergel’s group took several trips to the dojo over the course of about a year. Then, the LA Herald and Examiner, both very anti-Japanese at the time, learned about the white judo students going up to Manzanar.

"They'd print anything that anybody said without worrying about facts or anything else," Tichenor said. "Just the more horrendous they could make it, like, ‘Women students exchanging holds with Japanese internees.’ "

"Los Angeles girls are being taken to Manzanar by a Los Angeles policeman to wrestle interned male Japanese Judo style," the LA Examiner wrote on Aug. 28, 1944.

LA police commissioner Al Cohen called for — and got — an investigation into LAPD sergeant and sensei Jack Sergel. The commissioner called judo a form of "emperor worship" and demanded that Sergel be fired for taking these kids up to Manzanar to do it.

"He dreamt up the craziest fallacies," Tichenor said. "He didn't know what the hell he was talking about from the word 'go.' "

No charges were ever brought against Sergel. But around the same time, Tichenor said something else happened at their dojo in LA.

"I can remember the night that Jim Cagney showed up at the dojo and in the bleachers, watching us," Tichenor said.

"And he did it two times and then Jack got to talking with him and everything. What Cagney was looking for was for somebody to take place of this Japanese police captain in the movie ‘Blood on the Sun.’ "

So in November of 1944, Sergel resigned from the LAPD. He changed his name to John Halloran and started his career in Hollywood movies, beginning with 1945's "Blood on the Sun." It featured a judo fight scene between Cagney and Sergel — or Halloran — who was made up to look Japanese and played Captain Oshima.

"I think he was making money and getting into the movies, and he didn't need the police department and all the guff they were giving him," Tichenor said. "Why he changed his name just because he was in the movies — I don't know, maybe because he got away from the stigma he'd gotten with the police department on judo."

Clyde Tichenor stuck with judo and helped to teach it. Richard See fell away from the sport.

And if you look closely at old films like "Rosemary's Baby" and TV shows like "The Lone Ranger" and "The Cisco Kid," you just might spot the man who brought groups of athletes to a Japanese-American internment camp to do judo.

This segment aired on August 18, 2018.