Advertisement

How One WNBA Player Found Her Purpose In Poetry

This story includes mentions of sexual abuse and attempted suicide.

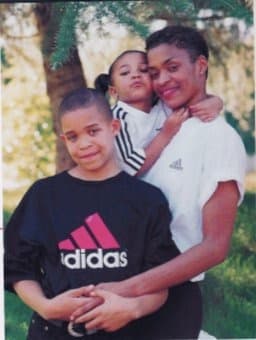

Imani McGee-Stafford grew up in an athletic house. She was always surrounded by basketball. You may have heard of Imani’s older brother, two-time NBA champion JaVale McGee. Or her mom, WNBA Hall of Famer Pam McGee.

"I did theater, I did computers," Imani says. "I definitely thought that I was going to be the one person in my family that didn’t play basketball. I was really adamant on it."

Imani ended up in the WNBA anyway. But it took a lot more than basketball to get Imani to where she is today.

'Maybe Something's Going On'

Imani McGee-Stafford says her childhood was confusing. She got good grades, she laughed a lot — but something didn’t feel quite right.

"If you looked at me quickly, you wer,e like, ‘Oh, OK, she's fine — she's doing great,’ " Imani says. "But once we have a conversation … like, I had a really dark sense of humor. Really cynical. Really critical. And then you figure out, ‘Oh, maybe something’s going on.’ "

Imani’s parents divorced when she was 3 years old. She spent her early childhood living with her father, Kevin Stafford.

"I was daddy’s girl — like, umpteenth degree," Imani says. "On his hip at everything."

When Imani was 8, her dad remarried. One day, when she was 10, her 15-year-old stepbrother was babysitting.

"And they had said, ‘Don't leave her alone,’ because I was the nosiest kid ever," Imani says. "And, of course, teenage boy goes and starts playing video games, or whatever. I discover my parents’ divorce papers."

Advertisement

Pam McGee’s and Kevin Stafford’s bitter divorce had been high profile years earlier.

"And I, like, run into my room, sneak in there, and I just devour it," Imani remembers. "Read the whole thing. And from there it just went downhill."

Imani’s father had argued in court that Pam’s WNBA career prevented her from being a good mother. There were allegations of abuse and neglect on both sides.

"I don’t know if you ever know how to digest that information, even as an adult," Imani says. "Figuring out that your parents are human. And that you may have been hurt. Or somebody dropped the ball in protecting you as a child. That's hard, especially for a 10 year old."

"Ten was actually the first time I tried to commit suicide," Imani says.

Imani’s stepbrother told her father about her suicide attempt, and she started going to therapy. When the family couldn’t afford it anymore, she stopped. It would be years before Imani unpacked the full extent of her trauma.

A New Lifeline

Meanwhile, in middle school, Imani found a new lifeline.

"I always thought I was going to be a singer," Imani says. "And when I was younger, I actually took it serious — I wrote songs. And when we got to seventh-, eighth-grade English, we started reading the diary of Anne Frank. Tupac. And I just discovered the world of poetry and fell in love. And immediately just abandoned music altogether.

"And poems and poetry just became my thing. Just being angry and sad and being able to write those feelings down was definitely cathartic for me."

Imani started using library computers to watch videos of poets performing their work. She wrote poems about her life and performed them for the first time.

"Little did I know, performing poetry at a middle school talent show isn’t the coolest thing," Imani says. "And I spent the whole year being made fun of for it. And while it was highly embarrassing, the entire experience kinda gave me more love for the stage."

And having cleared 6-foot-5 as a middle schooler, Imani finally started playing basketball.

"Eventually, it made more sense, because, you know, not many 6-foot-7 female roles are written ..." Imani laughs. "On one end, [basketball] made me kind of feel inadequate. Or, I had this huge expectation, and it sucked. As soon as I walked in the gym, people asked me how my mom was. And it was just, kind of, a reminder of somebody that wasn’t there.

"And then, on the other hand, it was my peace. To go in the gym and shut out the world — it didn’t matter what was happening. But, as soon as I walked in practice, like ... ‘Ah’ ... I could breathe. None of that stuff mattered."

'I Started Remembering Things'

In high school, Imani developed as a basketball player. Colleges started to recruit her.

But then …

"We're in class," Imani says. "And I’m taking a psychology class. And we're reading about abuse — and the triggers of abuse and what abuse victims look like. And I’m literally seeing myself on the page. Like, seeing habits I have. Behaviors I have. Things I do.

“When you’re being abused or going through abuse, if you don’t know better, you think it’s normal.”

Imani McGee-Stafford

"And then, on the other side of that, I now have my first-ever boyfriend. And we’re talking about sex and what that looks like in our relationship. And that's when it, kind of — I start having really bad nightmares and night terrors — and remembering things. Like, I barely could sleep. And that’s the first time I was like, ‘Wow, I was sexually abused.’ "

Imani says her abuse started when she was 8 and lasted for nearly five years.

"When you’re being abused or going through abuse, if you don’t know better — which most kids don’t — you think it’s normal," Imani says.

Imani attempted suicide two more times in high school. She spent the first three weeks of her junior year receiving intense treatment in an institution. But she still didn’t tell her father about her sexual abuse.

Imani and her dad fought. She was kicked out of the house multiple times.

"I started getting high," Imani says. "I started acting out in every way possible."

By this time, Imani had committed to play college basketball at the University of Texas. But soon, even that was in question.

'She Just Understood'

"I’m kicked out of my house," Imani says. "I just got kicked out of school, unofficially. And, at same time, Gail Goestenkors, the coach that recruited me to Texas, has resigned. So I technically don’t have a college scholarship. Because when it rains, it pours."

Then, Imani got a call from Texas’ new head coach, Karen Aston.

"It was so much easier for her to just say, ‘This kid has problems. I’m good. Let me get the next five-star recruit,’ " Imani says. "And instead, she asked me what's going on. I told her. I told her about my abuse. I told her I got high. I told her about my suicide attempts. And she just understood.

"I’ll probably never know why she tried and gave me the chance that she did. But God — I thank God for her."

Playing basketball at Texas meant a full scholarship, access to on-campus mental health resources and the opportunity to move away from home. Imani graduated from high school in 2012 and joined Karen Aston’s team in Austin that fall.

“I think poet is who I am, and basketball is what I do.”

Imani McGee-Stafford

But things didn't get better right away. I asked Imani what her college teammates would say about her as a freshman.

"My God," Imani laughs. "They would run you outta here. ‘Man, you don’t know how bad this little knuckleheaded 17-year-old that stepped on Texas' university was.’

"I was a naturally smart kid in high school, but I had no study habits, whatsoever. I didn't need 'em. And so, my first semester in college I was like, ‘Pssh, I don’t need tutors. What is this academic resources. I don’t need this. I don’t need that.’ And at the end of the semester I had a 2.7 [GPA]. And it shattered my little heart.

"And now academics is, like, ‘Can we help you? Let us help you. You don’t have to do it alone.’ And acknowledging that it was OK to ask for help — and me needing help didn’t make me any less human, any less successful, any less strong, powerful, whatever — was easily the biggest lesson."

And even though Imani says she was stubborn as a mule, her basketball teammates stepped up, too.

"To be able to have that safety net — that feeling of, ‘We love you even when you kind of suck’ — was new for me," Imani says. "It was the first time I really knew a community — or a family, per se — that I felt loves me regardless."

Imani was named the Big 12 Rookie of the Year in 2013. And a few weeks after her season ended, she came across information for the Austin International Poetry Festival.

"And I drag my boyfriend to it," Imani says. "God bless his heart."

Imani describes slam poetry as competition for artsy folks. Poets read their work, and audience members score them from 1 to 10. She wasn’t planning on performing, but an organizer convinced her to get on stage.

"And I read the poems on my phone," Imani says. "And I get fourth place overall.

"I started going to slams and open mics — and listening to people who didn’t necessarily look like me or come from where I come from express the same emotions that I felt. Express the same events, or the same things, that have happened to me in my life."

Imani added a new part to her routine. After morning classes and four-hour afternoon practices, she’d rush to different coffee shops and venues around Austin to attend poetry slams.

"I found a community in poetry," Imani says.

The summer after her sophomore year, Imani traveled with the Austin youth slam team to a competition in San Francisco. UT Athletics sent a video production team with her to film a short segment for Longhorn Network.

"I guess they thought I was gonna be talking about rainbows and sunshine," Imani says. "And I’m up there talking about being molested as a child."

“Just being angry and sad and being able to write those feelings down was definitely cathartic for me.”

Imani McGee-Stafford

It was the first time she directly addressed her abuser in a poem she performed.

... Back then we were the same height

You convinced me that playing house

Included far more than what Barbie and Ken came equipped with

That if I wanted to be an actress

I was never too young for a sex scene

It wasn’t like SVU

I didn’t scream

Stabler never came to my rescue

This was normal ...

"The producer comes up to me, and he’s, like, ‘Hey, what are you talking about?’ Like, ‘Are you comfortable talking on camera about what your poetry is about?’ " Imani remembers. "So I tell him my story. And I just tell him everything."

What Imani didn’t know is that Longhorn Network is owned by ESPN. So when the segment was finished, ESPN was the first to see it.

"They like it — they bump it — and it just keeps getting bigger," Imani says. "Now they’re running this story during March Madness, on SportsCenter prime time. On ESPN. And I’m freaking out.

"And the first thing, I was was scared. People I grew up with didn’t know this. My grandmother found out things on that special that she didn’t know. And I just felt very naked.

"But then, the craziest thing happened: so many people reached out to me and were, like, ‘We support you.’ Or, ‘We’re so proud of you.’ Or, ‘We’re so sorry you went through this.’

"My teammate — her mother came up to me, bawling. Like, ‘You just told my story, and I’ve never told anybody in my life.’ "

Other people shared similar experiences.

"That kinda changed the trajectory of my life," Imani says.

Athlete And Artist

Imani just finished her third season in the WNBA. She sees her therapist when she needs to, keeps a daily prayer journal ... and writes poetry.

"I just wrote a poem the other day," Imani exclaims. "It’s my happy place."

Imani says that by being unashamed about her journey, she’s been able to live the life she wants to. This past summer, she published her first book of poetry and held a book signing.

"All of my teammates on the Dream showed up and purchased a book," Imani says. "I was so freaked out. And my coaches came. And they all took pictures and posted about it and bought a book. I was such a big sap at the end of the day — like, they couldn’t see it, but when I went home, I cried happy tears.

"As much as I would like to think I’m the next poet savant, it’s really just because I play basketball. And it’s different for people to be both athlete and artist. Not all of us are given the platform to do both, the ability to do both or the courage to do both.

"I consider poetry air. It was my way to exhale — my way to express things that I didn’t know how to say — while basketball was confidence. It was the ability to feel like I was bigger than whatever I was going through. When I made a free throw — or got a good block or rebound or whatever — I just felt so much bigger than whatever was trying to kill me.

"So I guess I'm a poet first. But I think, like, poet is who I am, and basketball is what I do."

If you or somebody you know are in crisis, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is available 24/7 at 1-800-273-TALK. That’s 1-800-273-8255.

Correction: An earlier version of this story stated that Imani McGee-Stafford had just completed her second WNBA season. In fact, she just completed her third WNBA season.

This segment aired on December 22, 2018.