Advertisement

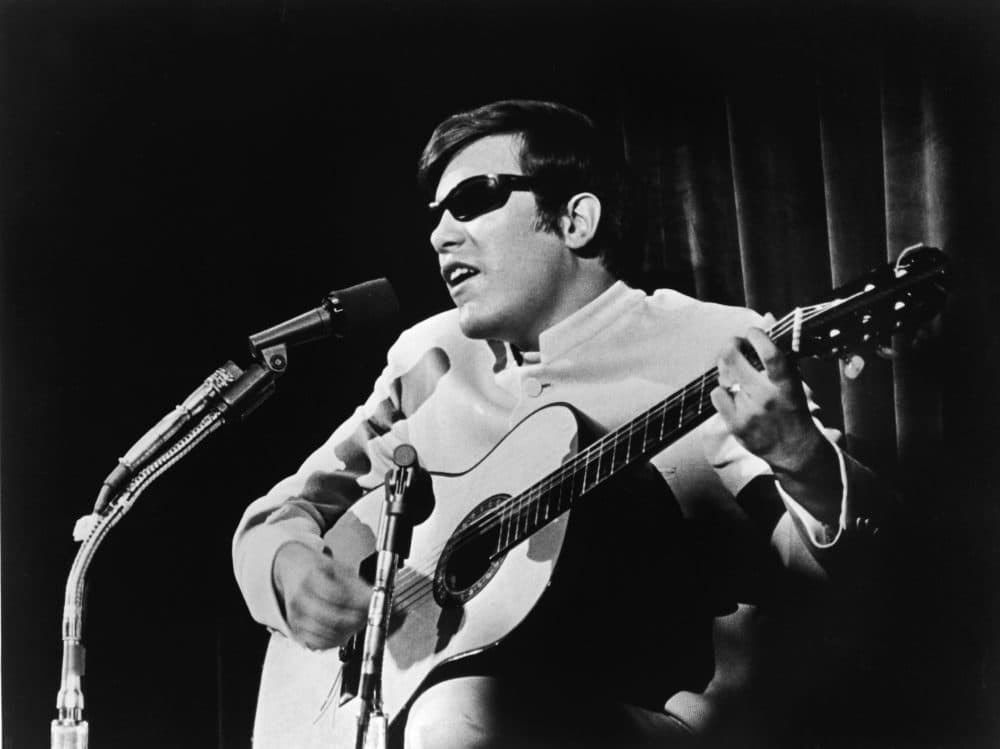

The 1968 National Anthem Performance That Changed José Feliciano's Life

José Feliciano’s life began in Puerto Rico. Congenital glaucoma left him blind at birth. Five years later, he moved with his family to New York City. He learned to play the accordion and then mastered a $10 Stella guitar.

He says he would practice 14 hours a day.

"To me, it meant everything — because it took me a while to learn to play it, because I taught myself," Feliciano says. "When I would get home from school, that's where I went — to the guitar, immediately. I tuned into American Bandstand, and I would play with whatever records they played at that time."

Feliciano started playing coffee houses in Greenwich Village, then clubs around the country. In 1968, he won two Grammys, and his version of The Doors’ "Light my Fire" rocketed to No. 3 on the charts.

That year, he also caught the attention of someone in the Detroit Tigers organization.

The 1968 World Series

"I heard about this young Puerto Rican, blind, who had burst on the scene," says late Tigers announcer Ernie Harwell in a 2009 video recorded by the Detroit Free Press.

Harwell was an amateur songwriter. So Tigers General Manager Jim Campbell had tasked him with recruiting anthem singers for the three 1986 World Series games in Detroit against the St. Louis Cardinals.

For Games 3 and 4, everything went according to plan. First, nightclub singer Margaret Whiting took the field. Then, it was Motown star Marvin Gaye.

"It was a little ironic that Campbell asked me, ‘Would you please go to Marvin and ask him not to give too much of a soul rendition?’ " Harwell says in the 2009 video. "So I did. And he said, ‘Yeah, I’ll sing it straight.’ "

Advertisement

But Feliciano says Harwell never asked him to sing the anthem straight.

"He didn't have a chance to talk to me, which I'm glad of," Feliciano says. "Because if I'm told not to do something, I'll do it anyway.

"I had been working on a version of the anthem ... oh, at least a year before that. But it was totally radical and different than what I did. And I said, ‘Well, José, you know what? Maybe you shouldn't be so radical and do it a little bit easier for them to listen to — and know that you weren't messing around with the anthem.’ "

The 23-year-old Feliciano walked with his service dog to center field, settled onto a stool and cradled his guitar.

"That came out of nowhere. We weren’t expecting anything different," says former Tigers pitcher John Hiller. "We said, ‘Oh, my God, Ernie — what did you do?’ "

Former Tigers pitcher John Warden was was standing near Hiller on the third baseline.

" ‘Holy cow, what's that? What's he doing?’ " Warden remembers thinking. "And everybody's looking around at each other. And you can hear the fans are sort of — you hear that background rumble."

"Well, I heard some cheers, but they were very sparse," Feliciano recalls. "And I heard a lot of boos. And I said, ‘Wow, what did I do? Why are they booing me?’ "

“I said, ‘I'll fix it.’ Well, it fixed me for a while.”

José Feliciano

I asked Feliciano when he really got the idea that there was a controversy.

"Well, when I went to my seat, because I watched a couple of innings," Feliciano says. "I had to head back to the airport and back to Las Vegas. I was thinking to myself, ‘Wow, what did I do?’ And Tony Kubek, who was a broadcaster then, came to me and said, ‘You've caused some commotion here. The phones for NBC at the network have been ringing.’ "

A Fan Club

But some people in Detroit, like 14-year-old Susan Omillian, loved hearing a new sound for the same old anthem.

"I was in class. On the way home, I heard that something had happened at the ballpark," Omillian says. "People were talking on the streets, on the porches along the way. When I got home, during the news, they showed a clip of this guy playing the guitar and singing the anthem as no one had ever heard. And it was like, ‘Wow, this is cool.’

"There was so much negativity that I thought was unnecessary, uncalled for, unfair. I don't know, a 14-year-old, what do they do? Back in those days, if you're me, you start a fan club."

We'll get back to Susan Omillian later.

I ask Feliciano why he sang the anthem the way he did.

"Because I was sick and tired of hearing it the old way and the audience, kind of, not being into it," Feliciano says. "Get to the end of the song, and the audience would start clapping as if to say, ‘Thank God this thing has passed.’ And I got tired of that. I did. I really, really did. And I said, ‘I'll fix it.’ "

"You sure did," I say.

"Well, it fixed me for a while," he says. "You know, my records were stopped. People at radio stations stopped playing my records. They wanted to deport me. But you can't deport a citizen of the United States. But it was funny to me. I thought, ‘Where the hell am I going to go?’ "

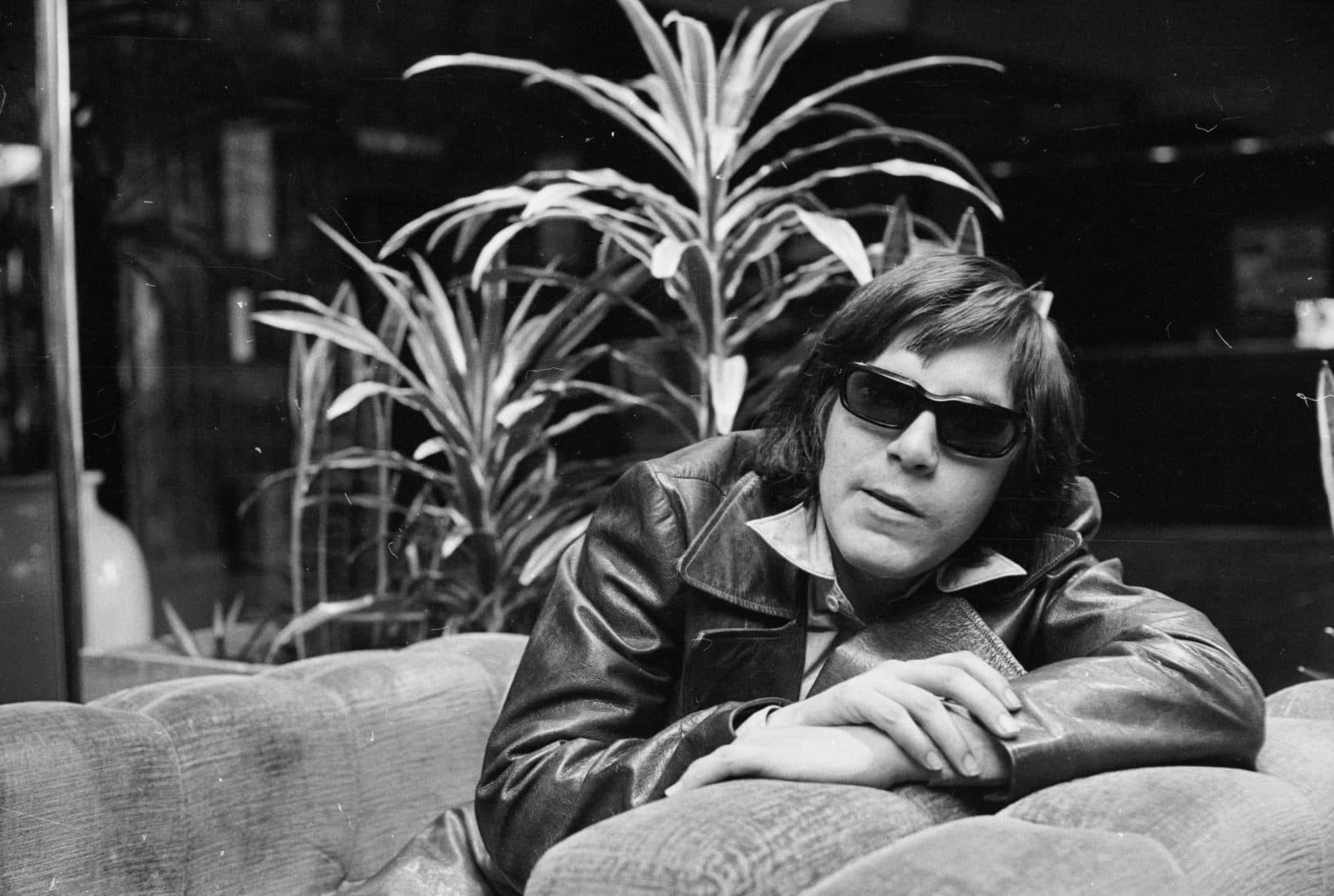

Fifty Years Later

Fast forward 50 years to Sept. 8, 2018. José Feliciano was in Detroit to sing the anthem again at a Tigers reunion. Before going to the ballpark, he met fans in a crowded room at the Detroit Historical Museum. As Feliciano answered their questions, his wife sat in the front row.

Feliciano improvised a serenade.

"Everything I do, Susan, I do it for you," he sang.

Susan — Susan Omillian — is the same Susan who started the fan club for José Feliciano back in 1968. She met him three years after his historic anthem performance in Detroit.

"By the end of the week, he was having dinner at my house," Omillian says. "And we went to Boblo — the amusement park. My dad was in the hospital at the time, and so he wanted to visit him. So, he brought a guitar and gave him a little concert at the hospital."

They've been married for 36 years.

"We married on our 11th anniversary of having become friends," she says.

They have three children. And Feliciano rebounded after that ’68 performance. His long career has produced 45 gold and platinum records.

At The Ballpark

A few hours after his appearance at the Detroit Historical Museum last year, Feliciano arrived at Comerica Park. He walked to a stage near second base to perform before a Tigers regular season game against the Cardinals. He wore a Tigers jersey with "Feliciano 68" on the back.

I ask Susan Omillian what it was like for her to see him perform the anthem 50 years after the 1968 World Series.

"Oh, my goodness," she says. "It was a really important moment, because it defined his life in such a negative way for so long. It was magnificent. I wanted my town to let him know how they really felt — how we all as a people really feel. I think we've grown since 1968. And so we've gone full circle."

The rendition was about the same as the performance from 50 years ago. But Feliciano wasn't using the guitar from 1968. It had been donated to the Smithsonian National Museum of American history a few months earlier.

On that day in Washington, D.C., 20 people from 17 nations took the oath of citizenship. Feliciano gave the new Americans a message. It was in his heart long before his 1968 World Series performance.

"I welcome you all with open arms," he said. "And this is America. America will always be great because of the people who come to it and make their homes here. Thank you so much, and congratulations."

This story was produced by Zak Rosen. A longer version aired on the podcast "Mismatch."

This segment aired on March 23, 2019.