Advertisement

Lessons From Watching Dad Find Ping Pong In His 70s

Resume

This ping pong table has become the site of a showdown. It’s the O.K. Corral of table tennis.

But, instead of multiple gunslingers on either side, there are only two old men holding paddles.

And one is my father.

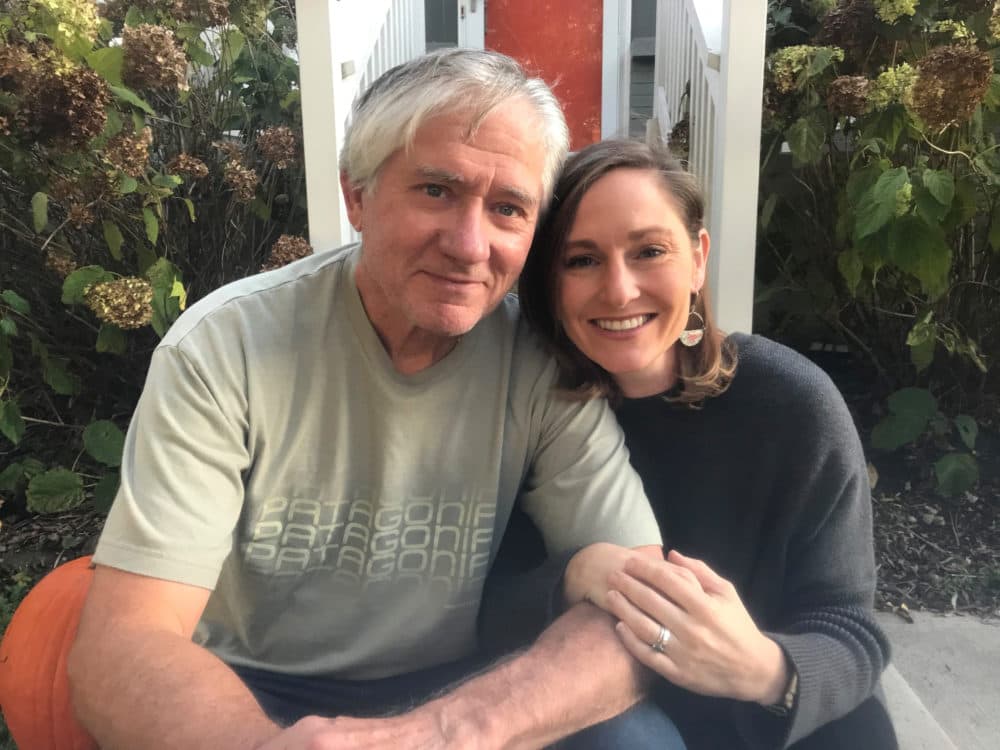

My dad, Jay Arenschield, is crouched like a shortstop, swinging his arms to keep his muscles loose, stopping once to brush his white hair out of his eyes. His opponent, a 74-year-old Californian named David, looks tough, if slightly stoop-shouldered — lean frame, tanned skin, what appears to be a tailored polo shirt. The man’s eyes are locked on my dad. His mouth is set in a fierce line.

They volley. David wins the first point.

From the sidelines, Dad’s youngest brother — my 65-year-old uncle Ricky — claps his hands. "C'mon, Jay. Don’t let up," Uncle Ricky says. "You get an offensive shot, you take it."

"C'mon, Jay. C'mon, c'mon," adds their friend Kerry. "C'mon, man. You got this."

We’re in Albuquerque, NM, for the 2019 National Senior Games, a once-every-two-years Olympic-style event that invites athletes ages 50 to over 100 to flex their athletic prowess in everything from archery to pickleball.

The whole thing feels surreal: Dad is competing on a national level in a sport he only started taking seriously a couple years ago, in his 70s.

David is kicking my dad’s butt, blasting every shot off corners and sending my dad lunging in wild directions. Dad is sweating, breathing hard. But he’s also grinning and laughing and making jokes. He’s flashing smiles at my mom, basically flirting.

And I think: When I am 73, please let me have this kind of life.

'Strict "No-Ping-Pong-At-Least-For-Now" Orders'

My dad’s ping pong group is something special, a diverse group of mostly older men at a time when "diversity" and "older men" are not phrases I often connect.

The group started five or six years ago when one of my dad’s friends, Dhia Aldoori, a physician who fled Iraq during Saddam Hussein’s reign, realized he needed something to keep his body moving as he got older.

After some research, Dhia — everyone calls him "Doc" — settled on ping pong.

It didn’t take long for the group to start playing in small competitions. By the summer of 2018, Dad had qualified for the National Senior Games and, after that, he and his friends started training in earnest. They traveled to other ping pong clubs, testing themselves against different players. Doc hired a coach, a kid in his 20s who is trying to make the actual U.S. table tennis team. My dad started watching what he ate — fewer late-night potato chips, more vegetables.

Last spring, Dad’s training was on pace, and his game was getting stronger. He and my mom booked a bed and breakfast in Old Town Albuquerque for a week around the Senior Games, and she started making plans to visit Santa Fe and the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, to sample New Mexico’s famous chile rellenos.

And then, my dad cut off his finger.

It was April 17, nine weeks before the National Senior Games, when my mom’s number flashed on my phone. It was just before lunchtime on a workday — a strange time for her to call.

"I don’t want you to worry," my mom started — and if the words had had physical form, they would have quivered — "But we are in the emergency room.”

Dad had been in the middle of a woodworking project, sawing a chunk of wood into smaller, thinner pieces, when the blade sucked in the shim he’d been using as a guide, dragging Dad’s finger along with it. The blade sliced his index finger neatly at the first knuckle.

He was lucky in a few regards. One: The doctors thought that his finger could be reattached, so he might not lose it entirely. Two: He hadn’t lost much blood. And three: The finger happened to be on his left hand. His right hand — his paddle hand — was unharmed.

Doc was the first person to show up at my parents’ house after the table saw accident. Dad was under strict "No-Ping-Pong-At-Least-For-Now" orders from his doctor.

Doc wanted to make sure my dad wasn’t lonely.

A couple days later, Rob, my dad’s doubles partner, called to see if Dad wanted to go to lunch. Uncle Ricky came over and cut the grass.

When Dad went back to practice — of course, he went back to practice — the doctor said he needed to keep his injured finger safe. That meant no lunging in ways that might cause him to fall, no swinging his arm as he served and accidentally knocking it into a table or wall.

Dad’s friends policed this the same way they played ping pong: mercilessly.

'If He Loses Again, He’s Out'

At the National Senior Games in June, the air inside the Albuquerque Convention Center is filled with the rhythmic sounds of ping pong balls bouncing off tables and shoes squeaking on a linoleum floor.

Dad’s finger is mostly healed, but not quite. Per his doctor’s orders, it is still set in a splint and wrapped tightly in an elastic bandage. He can’t move it at all.

On the court, things are not going well. When David wins game three, a shutout match, my dad places the ball on the table, shakes David’s hand and walks over to the sidelines where his friends and my mom are waiting.

"Don’t give up, Jay," Kerry says.

Dad takes a swig of water, pulls a towel across his neck and heads back out to the court to face the next competitor.

If he loses again, he’s out.

The First National Win

Dad’s second match is against a tall, lanky, friendly guy — a semiretired pastor at a Lutheran church in Minnesota. The first game starts out OK: Dad scores a couple, the pastor scores a couple, and then the pastor pulls ahead, up by two, up by five. Maybe a higher power was pulling for the pastor, maybe Dad was just too nervous, or maybe the pastor was just better at ping pong, but it’s a deflating start for my dad.

Kerry leans over to me. "He’s gotta get some confidence going forward, just a little spark," he says in a low voice.

Game two has already started and, almost immediately, my dad picks up a great point and goes on a roll. Game two: Dad. The match is tied.

"The pendulum just swung," Uncle Ricky tells my dad. "Now you got the momentum."

Dad wins game three and goes up two games to one. One more will give him his first win in a national tournament match.

Dad scores again and again, and soon, it’s 7–4, Dad, and now, Kerry and my uncle are on their feet.

But then the pastor starts scoring.

7–5. 7–6. 7–7.

Tie game.

"Jay, I want you to get an attitude, man," Kerry shouts, and maybe that clicks, because Dad starts scoring again. Before long, it’s 10–8, and then Dad is sending the ball over the net and the pastor can’t get there in time.

11–8. Game and match.

Dad’s first national win.

We have choices about how we age that start as soon as we are old enough to create our own destinies. We can smoke — or not. We can wear sunscreen — or not. We can drink too much — or not. We can eat more produce and fewer potato chips, move our bodies a little bit every day, learn new things, get enough sleep, keep our connections to friends and families strong — or not. None of these things guarantee a long, happy life. But they sure don’t hurt.

From my dad and his ping pong friends I’ve learned: We can approach life like it’s something to be survived and endured, something to be fought, something to be beaten. We can give up when something tough happens, sink back into our easy chairs and never get up again. Or we can wrap life in our best embrace and allow ourselves new experiences with new people in new places. We can challenge ourselves. We can be kind and loving and supportive to the people around us. We can bask in the love that shines our way as a result.

And we can get on a court, even in our 60s and 70s and 80s, even with a partially sawed-off finger, and we can compete.

Laura Arenschield is a writer. A longer version of this piece was originally published in Southwest: The Magazine.

This segment aired on December 7, 2019.