Advertisement

Closing The Book On The 2014 Governor's Race

The 2014 governor's race was a second shot for both Democrat Martha Coakley and Republican Charlie Baker, both of whom lost statewide elections in 2010. What each candidate had learned from their previous defeat was a major part of the narrative of this fall’s campaign. The election results show that both Baker and Coakley improved on their showings from 2010. But Baker improved more, and it was his improvements in several geographic and demographic areas that account for his narrow win.

The Lay Of The Land

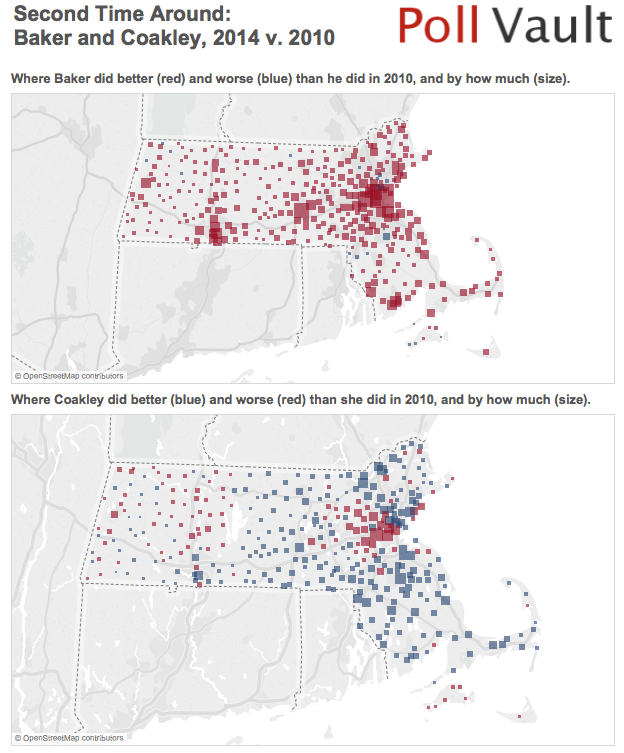

The two maps below show where each candidate did better and worse, in terms of the voter margin over their opponent, this time compared to their previous contests. The sea of red on Baker’s map indicates that he improved in almost every city and town. Even in places where Coakley won — Western Massachusetts, cities and liberal suburbs near Boston — Baker improved on his showing against Gov. Deval Patrick.

Coakley’s map is more mixed. The blue shows that she improved in many suburban towns compared to her outing against Scott Brown, but she still lost those communities to Baker. The red in the communities that she won — again, Western Massachusetts, cities and liberal suburbs — shows that she actually lost ground in the places where she needed a strong showing.

Zoom In On Boston

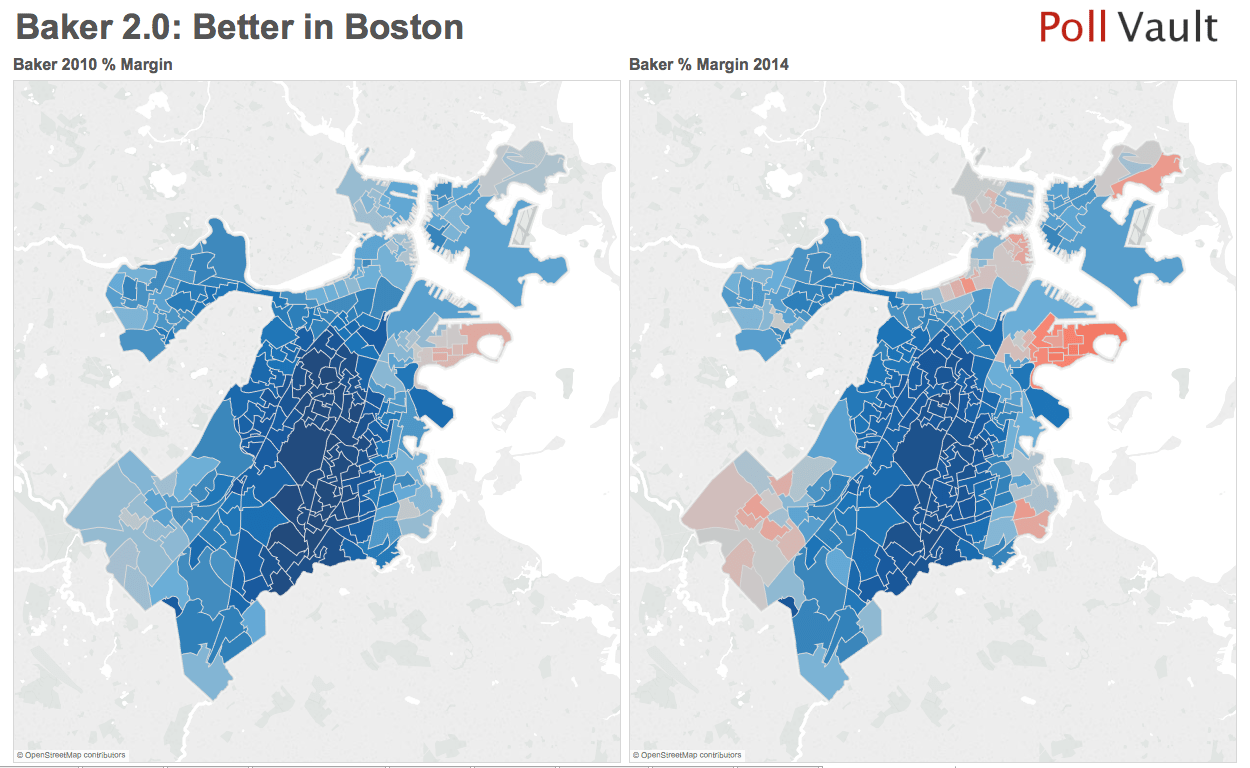

In 2010, Baker lost Boston to Patrick by a whopping 47 points. This year, after much campaigning in the city, including in communities of color, Baker improved his performance, losing by 36 points there. It may sound odd to trumpet losing by three dozen points as a good outcome, but it’s actually two points better than Scott Brown fared when he beat Coakley by 5 points statewide in 2010. In an article for CommonWealth magazine last spring, we estimated that a Republican would have to keep his or her losing margin below 40 points in Boston in order to have a chance statewide. Baker did that, and he won narrowly.

In terms of raw votes, Baker gained 10,000 or so in Boston over his performance in 2010, while Coakley lost votes there compared to her 2010 race, and especially when compared to Patrick in 2010.

The two maps above show that Baker actually flipped several precincts in Boston from blue to red: parts of the Back Bay and downtown, Charlestown and East Boston, and vote-rich West Roxbury and Dorchester. He also won more of South Boston and by a larger margin than he did in 2010.

Less visible on the maps but also significant is that Baker managed to whittle away at Coakley’s margins in the most Democratic precincts, the majority-minority areas in the center of the city. Overall, Baker lost majority-minority precincts by an average 67 points — nothing to brag about, but 10 points better than he did against Patrick in 2010.

Baker managed to replicate this feat in many of the Gateway Cities, trimming Coakley's margin compared to Patrick’s by 16 points in Worcester; 14 in Pittsfield; 11 in Springfield and 10 in New Bedford and Fall River. In other Gateway Cities, Coakley held her own, particularly cities like Lowell and Lawrence, which have large non-white populations.

Advertisement

Race And Income Trump Party

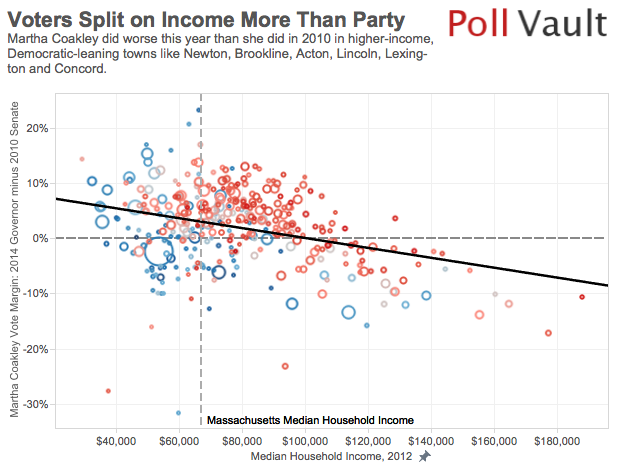

Given the Baker campaign’s overtures to urban voters, his gains in cities are not surprising. What is surprising is that Baker made significant gains in wealthier suburbs west of Boston that usually lean Democratic. In this respect, the 2014 election split more clearly along class lines than partisan lines.

Compared to her losing 2010 Senate run, Coakley gained ground in lower-income cities and in moderate-income Republican suburbs. But she lagged her own pace in wealthier suburban communities, regardless of whether they traditionally vote Democratic or Republican. Notably, Coakley struggled in every Democratic community where the median household income exceeds $90,000. This may also explain her losses to Baker in the wealthy Back Bay and Charlestown sections of Boston.

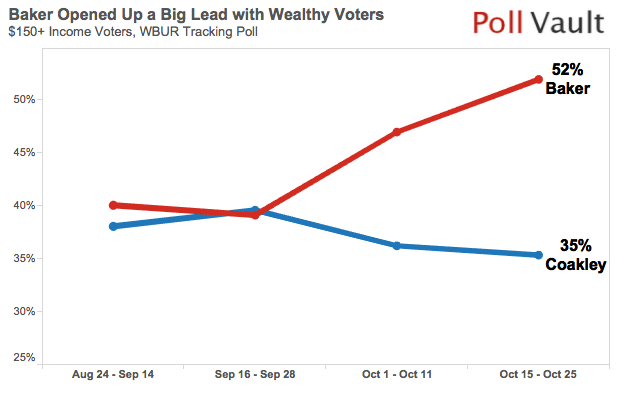

The WBUR Tracking Poll shows that Baker opened up a big lead with wealthy voters since the primary. In the first three weeks of the poll, Baker and Coakley were even with voters making more than $150,000 annually. By the final two weeks of polling, these voters favored Baker by 17 points.

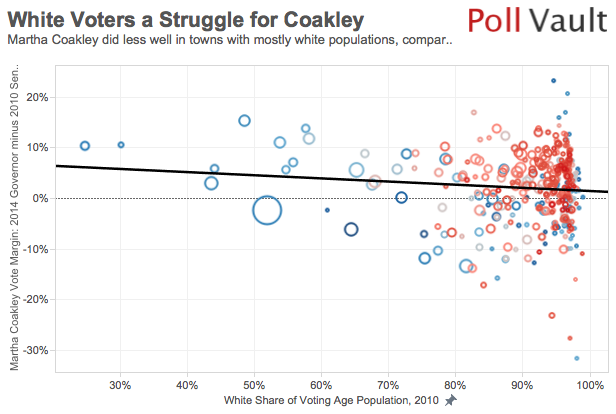

Race was also a key factor. Coakley improved on the margins from her 2010 Senate run in 10 of the 11 Massachusetts communities where non-white voters make up at least 40 percent of the voting-age population. She lagged her own benchmarks only in Boston, and there, only slightly.

Where she lost the most ground compared to her 2010 Senate run was in heavily white, Democratic-leaning communities. Coakley trailed her own vote margins from 2010 by 5 or more points in 22 cities and towns that had backed Patrick in 2010. Baker made inroads in white Democratic strongholds like Newton, Weston, Lincoln, Concord and Brookline.

Flipping The Script

At the beginning of the campaign, it was a legitimate question whether, after a string of big Democratic victories, a Republican candidate could still win statewide in Massachusetts. The demographics of the state and its major cities had been trending towards the Democrats in such a way that it seemed nearly irrevocable for the state GOP.

The narrowness of Baker's victory, despite an advantage in money and in the polls, shows that the state may well be heading in that direction, but it's not there yet. Baker won because he heeded the warning signs in cities and ran towards them rather than away from them. At the same time — and perhaps because he did so — he managed to distance himself from the national Republican brand enough that well-heeled liberals in Boston suburbs felt comfortable voting for him.

Baker's win has flipped the conversation around entirely. If Republicans can't win statewide when losing by 40 points in Boston, is the converse also true? Can a Democrat become governor without running up a 40-point margin in Boston? We'll have to wait four years to test that theory. That's not exactly why we have elections, but it's a nice side benefit. Thank you for exploring this year's race with us. We hope you enjoyed it as much as we did.