Advertisement

Dover Fights Lyme Disease With Bows And Arrows

Resume

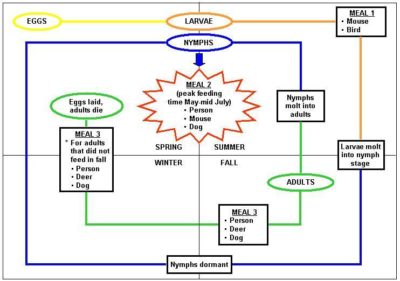

It's a common misconception that ticks pick up Lyme disease from deer. They don't.

Ticks usually acquire the Lyme bacteria from rodents or birds before passing it on to humans. But deer provide an abundant food source for ticks. And as the deer population has exploded across the Northeast in recent years, so has the tick population.

In parts of New England, Lyme disease is epidemic. This fall, one tick-ravaged town west of Boston is determined to do something about it.

Wolff Hunts Deer

The town is Dover, which is where I met Dan Wolff.

Wolff owns Mass. Deer Service, a company dedicated to "help[ing] residents of the MetroWest area deal with some of the issues of too many deer on their property," he says.

Seriously, he's Wolff the Deer Hunter.

"Alright, this is the Deer Mobile," he tells me as I climb into his custom truck. There are deer embroideries on the leather and antlers jangling from the review.

"Right now we're heading up to a property up on Farm Street," Wolff says as he navigates the winding roads of Dover — a green, well-to-do town with big houses on big lots. "The lady inquired last winter after deer season. She's got a large piece of property in a very high deer density area."

We park in front of an imposing, modernist country palace.

"You get to see the big dog in action," Wolff says as we walk toward the front door. "Now, my goal is to secure permission from this property owner to hunt the deer."

Deer-ravaged property owners don't pay Wolff to hunt deer. They just give him permission to hunt on their land and Wolff turns around and sells that permission to recreational hunters who are looking for a place to shoot. He vets the hunters for competence, sets them up with maps and documentation, and it's a match made in heaven.

"Prisoners In Paradise"

Wolff has had some problems with anti-hunting activists in the past, so he asked me not to identify any of the property owners he works with. This lady, we'll call her "Wendy," takes us out back to see her huge, grass- and tree-filled lot.

"So this is where we see them," she says, as Wolff surveys the lovely woods and meadows.

The contrast between Wolff the Deer Hunter and Wendy the Upscale Suburban Mom is striking. She doesn't seem like the hunting type.

"I love the Tetons," she says wistfully. "I've always been a, you know, 'give me a home where the buffalo roam' type of person, where I love sitting out here and seeing the deer. But once you have a kid who has Lyme disease, and you're bitten all the time, all of a sudden you have very different feelings about hunting the deer."

The deer tick population started to grow exponentially here around 2005, and now Dover is basically under siege.

Epidemiologists start to get worried about Lyme disease when there are about 100 incidents per 100,000 people. This town is now at 270. And that's put quite a damper on their enjoyment of these big ol' green lots.

"When we first moved in here, we used to take walks down to Rocky Narrows on trails and everything," Wendy recalls. "And with the huge tick problem we don't have any desire to do it."

"It's tough," Wolf says. "People are like, 'we're prisoners in paradise,' you know?"

No One To Blame But Themselves

At least one expert says the people of Dover brought this upon themselves. Sam Telford, professor at the Cummins School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts, says that humans caused the deer population explosion.

Telford says even though humans long ago killed off the deer's natural predators, we used to do a pretty good job of preying on them ourselves. That is, until suburban sprawl happened.

"More than 10 years ago," Telford says, "I and many others predicted that the corridor between Route 128 and Route 495 would become the new Cape and Islands with respect to Lyme disease and other deer tick transmitted infections, because of suburbanization.

"Each new house that goes in removes 18 acres of huntable land, at least by the most effective means of hunting, which is by shotgun."

The Solution Is In The Trees (With Bows and Arrows)

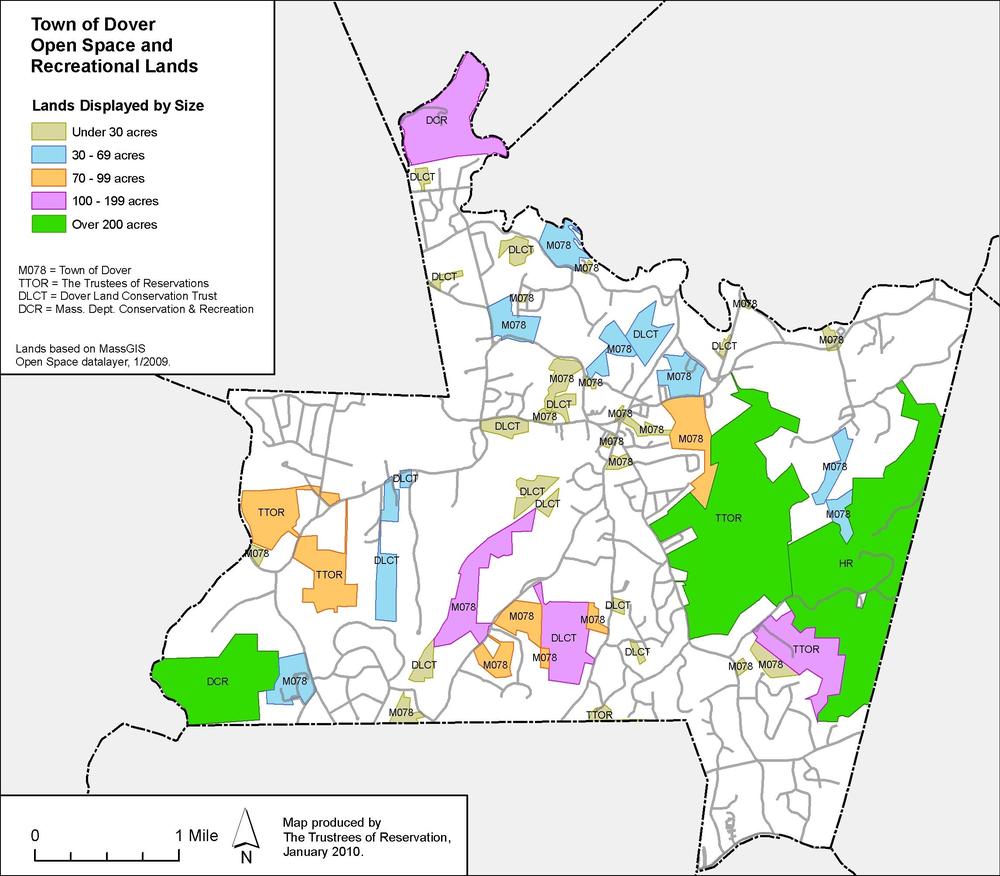

Dover's deer density is between 24 and 28 per square mile, according to Barbara Roth-Schechter, chair of the Dover Board of Health.

"The ideal density should be somewhere between 6 and 8 deer per square mile," Roth-Schechter says.

At the outside estimates, there's a deer for every dozen people in Dover. And while a shotgun solution might not be right for suburbia, the Dover board of health does have other plans.

"This year we have six town-owned properties to be opened to our bow hunting efforts," Roth-Schechter says.

Could she be talking about harpooning deer on the town green?

"Oh, for crying out loud, absolutely not!"

Actually, they're only going to do this in the more remote parts of Dover. It's jut a little pilot program happening on a few hundred public acres. To allay public anxiety, they're painstakingly interviewing and background checking the few dozen recreational bow hunters that will be allowed on the land.

"We're talking [about] bow hunting from tree stands, so you cannot shoot straight out," Roth-Schechter says. "You have to shoot down. And the greatest distance is between 15 and 20 feet."

The Deer Mobile Rolls On

Back in the Deer Mobile, Dan Wolff tells me that bow hunting in a suburban environment involves certain trade-offs.

"Yes, the range is much tighter, but it's much more challenging," Wolff says.

Wolff says bow hunters must have the discipline to wait for just the right shot to achieve a quick, humane kill.

"You really don't want to have injured animals running around with arrows in them where people can view them, especially young children," he says.

Wolff says he doesn't want a piece of Dover's first ever public land deer hunt. Too much red tape. For now, Wolff the Deer Hunter is content going door to door, getting homeowners' permission to hunt, and scoping their woods for prey.

Killing Deer "Not A Magic Bullet"

In the hour that I spent tromping around Dover with Dan I accumulated 20 ticks, that I know of.

Tufts professor Sam Telford says that's not unusual.

"15 years ago, if someone had told me 'oh, well there are deer ticks in back of your office,' I would have said 'you're crazy,'" Telford says. "But now if you came out and asked to see deer ticks, we would spend 10 minutes and we'd have deer ticks to see."

So how many deer do we have to kill to fix this problem?

"Well, killing deer is not a magic bullet," Telford says. "People have to manage their vegetation, they can clean up around their homes. These ticks need high humidity, so if you have brushy areas and lots of leaf litter, that's a great place for the ticks to develop. I've been caricatured as saying 'you have to kill deer and that's the only solution.' It's not."

I make a crack about "killing Bambi's mom," and Telford laughs. He gets that kind of grief a lot.

"Magic bullet" or not, bow-and-arrow hunting season starts in Massachusetts on Monday. And if communities like Dover want to reach what state wildlife officials consider optimal deer density, they'll eventually have to reduce their deer populations by as much as three quarters.

More:

This program aired on October 15, 2010.