Advertisement

To Catch A 19th Century Serial Killer

Boston author Douglas Starr loves mysteries — especially mysteries that involve blood. In fact, his first book was entirely about blood and its history in medicine and commerce.

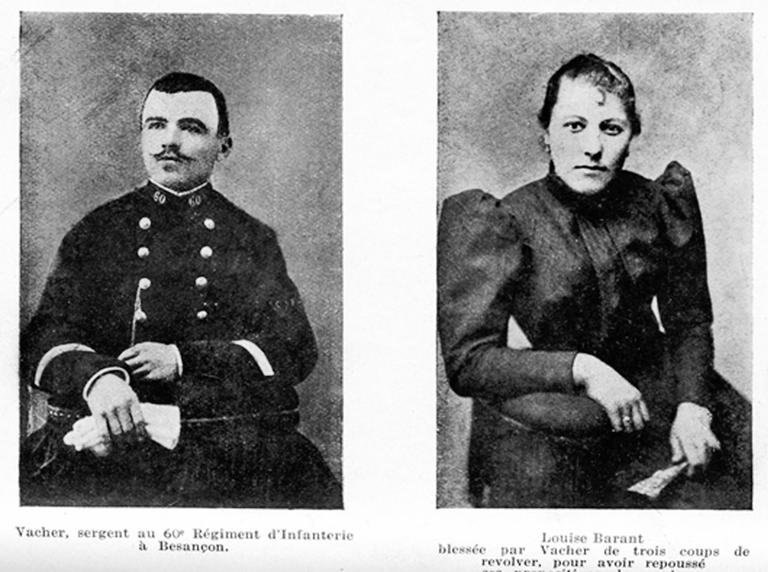

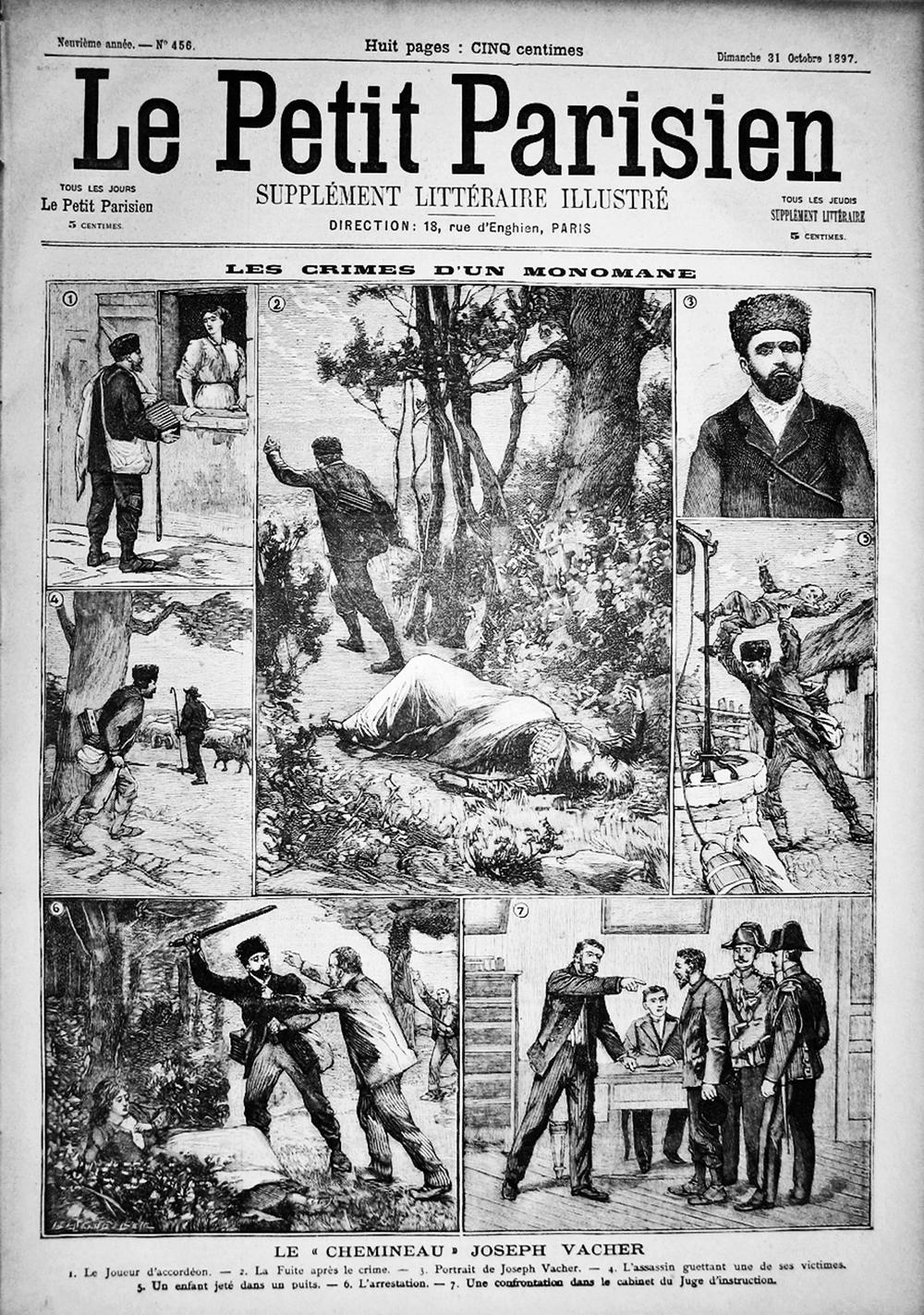

Recently, forensic science captured his attention. While poring through medical journals, the Boston University professor came across the case of 19th century serial killer Joseph Vacher and the scientist who helped bring him to justice, Dr. Alexander Lacassagne. In his latest book "The Killer of Little Shepherds: A True Crime Story and the Birth of Forensic Science," Starr focuses on these two characters and their contributions to the development of forensic science.

Guest:

- Douglas Starr, author, journalism professor, Boston University

Read an excerpt of "The Killer of Little Shepherds" below.

Book Excerpt: "The Killer of Little Shepherds"

Chapter 2: The Professor

In mid-November 1889, Dr. Alexandre Lacassagne, head of the departmentof legal medicine at the University of Lyon, got a request from thecity prosecutor to help with a particularly nasty case. Four months earlier, a body had been found in a sack by the Rhône River, about a dozen miles south of the city. The corpse had been autopsied by another doctor,who could not arrive at an identification. Now, because of new developments in the case, the body was being exhumed. Granted, there would not be much left of the cadaver, but could Dr. Lacassagne perform a new autopsy? Perhaps he could find something the previous doctor had missed. It was not unusual for Lacassagne (Lackasanya) to be called in where others had stumbled, for he had established a reputation as a skilled criminologist. As the author of textbooks, the developer of many new forensic techniques, and the investigator of several celebrated cases, he was first among equals in an international cadre of experts in the new field of legal medicine.

Advertisement

The subject of this autopsy was presumed to be a missing Parisian named Toussaint-Augustin Gouffé. A bailiff by profession, and a widower with two daughters, Gouffé was a prosperous man and had a reputation for being a sexual adventurer. On July 27, Gouffé’s brother-in-law, whose name was Landry, reported to police that Gouffé had gone missing. Police paid little notice at first—this was, after all, the summer of the Paris World Exposition, with many unscheduled comings and goings. But when three days passed without Gouffé’s reappearance, they took the case seriously, and referred it to Marie-François Goron, renowned chief of the Paris Sûreté, the city’s investigative unit.

Three weeks later, a body turned up about three hundred miles southeast of Paris, near the village of Millery, south of Lyon. A few days after that, some snail gatherers in the woods found a broken wooden trunk, which reeked of death and bore a shipping label from Paris.

Could the body and the trunk be connected to the missing man? Goron telegraphed a description of Gouffé to the medical examiner’s office in Lyon. At the time of the discovery, Lacassagne was away, so a colleague and former student, Dr. Paul Bernard, conducted the autopsy. He found little that matched the corpse to the missing person. True, the cadaver, like Gouffé, had large and strong teeth and was missing the first right upper molar, but that was about all. The corpse measured about five feet seven inches, while the missing man stood about five eight. The corpse had black hair; Gouffé’s hair was chestnut-colored. The cadaver was between thirtyfive and forty-five years old, according to Bernard’s estimate; Gouffé had been forty-nine. Just to be sure, Goron sent Landry to Lyon, along with a deputy. Landry took a brief, gasping look at the bloated, greenish body and saw not the slightest trace of his relative. Case closed. The men returned to Paris and the body went into an anonymous pauper’s grave.That might have been the end of the affair, but in the fall Goron received an anonymous tip. Just before Gouffé disappeared from Paris, he had been seen at the Brasserie Gutenberg in the company of a con man named Michel Eyraud and his consort, Gabrielle Bompard. The couple left Paris the day after Gouffé went missing. Meanwhile, Goron had taken the shipping label from the trunk and showed it to the clerk at the Gare de Lyon in Paris. Records showed that the trunk had been shipped to Lyon the day after Gouffé’s disappearance. Its weight was registered at 105 kilograms—just about the combined weight of a fully grown man and a stout wooden trunk.

Everything tied the victim to Gouffé—except for the autopsy. Goron felt there must have been a mistake. He contacted the authorities in Lyon and asked them to exhume the body and reexamine it. They resisted: By now the victim had been dead for four months; no one could possibly identify the remains. But Goron, legendary for his persistence, remained adamant. And so the hideous job of conducting an autopsy on a body that had previously been dissected and had lain rotting underground fell to the one man in Lyon—perhaps in all Europe—who stood the slightest chance of solving the mystery.

Dr. Jean-Alexandre-Eugène Lacassagne already was well respected in his field when he encountered the case that would make him world-famous. As one of the early scholars and innovators of legal medicine, he had helped devise many new techniques in crime-scene analysis, such as determining how long a body had been putrefying and how to match a bullet to a gun. He showed investigators how to determine whether a dead body had been moved by examining the pattern of blood splotches on the skin. He developed procedures by which even simple country doctors could perform professional autopsies if called to a crime scene. Colleagues admired him not only for his contribution to science but as a scholar, teacher, and friend. As people often did in those days, they saw his character revealed in his appearance—and a noble physiognomy it was, with a high forehead, handlebar mustache, burgomaster’s girth, and a “strong, rhythmic step and ever-cheerful eye.” With his energy and talent, he could have done anything, but he had chosen the nascent field of criminology. To his mind, it encompassed the scale of the human experience, from the workings of a single brain to the forces that shape civilization. But even that occupied only part of his intellect. He immersed himself in poetry, philosophy, literature, and art. He could recite from memory pages of Dante in the original Italian and entire acts from the work of his favorite French playwrights. He sponsored young artists. He was never without a book—either reading or writing one. His friends thought him a Renaissance man, except for one flaw: He lacked the ability to appreciate music.

He was born in 1843 to innkeepers in Cahors, a quiet town in southwest France. A gifted student but too poor to afford a private education, he attended the military’s medical school in Strasbourg, where he wrote his first thesis, on the side effects of chloroform. He studied military medicine in Paris for a year and then returned to Strasbourg. He arrived during the Franco-Prussian War, and for thirty-nine days the Germans bombarded the city before its ultimate surrender. As one building after another collapsed, Lacassagne and his fellow medical residents set up a clinic in the hospital basement, piling mattresses against the windows as explosions blew fiery debris all around them. In September, a Swiss delegation evacuated the wounded and doctors to a hospital in Lyon. It was Lacassagne’s first view of the city that would become his home and a world capital for the investigation of crime.

With the Strasbourg medical school destroyed, Lacassagne continued his studies in Montpellier. He wrote a thesis on putrefaction, manifesting an early interest in biological phenomena that affect both the living and the dead. To fulfill his military obligation, he traveled to Algeria, where he was assigned to be the doctor for a disciplinary brigade. Normally, it would have been a dreary assignment, but not to a man with an intellect as lively as Lacassagne’s. He became fascinated by the miscreants in his care. Many bore tattoos with strange and exotic images: Joan of Arc, the scales of justice, hearts pierced by knives, two hands clasped with a flower rising between them, and naked women with sexual features exaggerated to cartoonlike proportions. The inscriptions were equally fascinating: “No luck”; “Death to unfaithful women”; “Vengeance or death”; “Born under an unlucky star.” Convinced that the tattoos revealed insights into criminal subculture, he developed techniques to transfer the patterns to paper and then categorized them according to imagery and body location. By the end of his service, Lacassagne had categorized some two thousand tattoos from hundreds of soldiers. When he presented his research to an international meeting of anthropologists, the American journal Science described it as “one of the most entertaining and instructive anthropological papers which have appeared in a long time.”

From that point, his career path rose steeply. In 1876, he published a book entitled Précis d’hygiène privée et sociale (Synopsis of Private and Public Hygiene), a more than six-hundred-page volume about personal, public, and occupational health. Two years later, he wrote an equally weighty tome, entitled Précis de médecine judiciaire (Synopsis of Judicial Medicine), which summarized the nascent field of legal medicine. It was hailed as a small masterpiece. In 1880, he was named to the recently established chair of legal medicine at the University of Lyon. In this hardworking, bourgeois, insular city, he became popular among the students,not only for his knowledge but for his refreshing enthusiasm and warmth. Beyond solving individual crimes, Lacassagne became fascinated by the criminals themselves—their thought processes, subculture, and way of life. Why did they feel compelled to behave in a manner that was contrary to the rules of society? Why did they take such a difficult path? He made it his life’s work to find out, and studied them as assiduously as a zoologist would scrutinize a favorite species. He visited them in prison, collected their writings, and dissected the brains of those who had been guillotined. His findings, and those of his colleagues from Europe, Russia, and the New World, appeared in a journal he founded, Archives de l’anthropologie criminelle (Archives of Criminal Anthropology). For twenty-nine years, it served as the preeminent forum in the field. In its pages scholars would discuss the key developments of their day—crime-scene analysis, criminal psychology, capital punishment, the definition of insanity. There were also many practical reports, in which Lacassagne and his colleagues would describe how they used the latest forensic techniques, as in “the Thodure Affair” (pieces of an old man’s body found around a village), “the Father Bérard Affair” (a priest accused of sexual perversion), and “the Montmerle Affair” (a woman found hanged and stabbed in the throat). There were articles on celebrity cases, such as that of Oscar Wilde, in which a French expert on homosexuality wrote about the writer’s trial and imprisonment. Jack the Ripper appeared in its pages, as did Jesse Pomeroy, the boy killer of Boston. On two occasions the journal reviewed the newly published stories about Sherlock Holmes. (The verdict: fascinating procedures, but why did Holmes never conduct an autopsy? Also, real medical experts recruited teams of specialists, while Holmes worked alone, with Watson as a mere sounding board.) The journal was populated by the castoffs of society: thieves, murderers, child molesters—the human face of the degenerate instinct.

To assist in an autopsy with Dr. Lacassagne was to participate in a memorable educational experience. Medical students would have seen hospital autopsies before, but forensic dissections were something quite different.

Here they saw tableaux of violent death, displayed in a medium of shredded tissue and broken bone. Death leaves a signature, and they would learn to read the meaning: a peaceful death versus a violent one; a death by accident, suicide, or criminal intent. By removing an infant’s lungs and seeing if they floated, they would learn to determine whether the baby had been stillborn or had lived long enough to take its first breath. They would learn that a frothy liquid in the airways indicated drowning; that a furrow around the neck pointed to a rope hanging; that break points on opposite sides of the larynx showed that the victim had been strangled with two hands. They would use the angle of a stab wound to determine the trajectory of the arm that had held the knife, and the pathway of a bullet to deduce the location of the gun. They would employ chemical reagents to identify stains from blood, semen, fecal matter, and rust (often mistaken for blood). “The students all flocked to him,” recalled Dr. Edmond Locard, a student who himself became a prominent criminologist. And so, several times a month for the thirty-three years that Dr. Lacassagne taught at the medical faculty of Lyon, students would cluster around their beloved professor, who, with no mask on his face and no gloves on his hands, would slice into a cadaver to reveal the mysteries of the last moments of the deceased.

No crowd of students surrounded Lacassagne as he prepared for an autopsy on the morning of November 13, 1889—only a small number of medical assistants and police officials were in attendance. On the table lay the remains of someone who had died almost four months before. Was it Gouffé? Following the autopsy in August, after the body had been buried in an anonymous pauper’s grave, a clever lab assistant named Julien Calmail had a hunch that the body would be needed again, so he scratched his initials on the outside of the coffin and put an old hat on the cadaver’s head, creating a means of identification.

By Lacassagne’s side stood Dr. Paul Bernard, who had conducted the first autopsy, and an assistant, Dr. Saint-Cyr. There was also Dr. Étienne Rollet, Lacassagne’s student and brother in-law, whose recently completed thesis would prove invaluable to the case. The state prosecutor from Lyon stood close by, as did Goron, determined to get to the bottom of the mystery. Up in the far reaches of the amphitheater, with a handkerchief pressed against his face, stood one of Goron’s colleagues, Brigadier Jaume. One could forgive Jaume for keeping his distance, as the sight must have been appalling. A four-month-old cadaver retains little of the appearance that once identified it as human. Having been ravaged by insects and having passed through several stages of putrefaction, the body is little more than shapeless clumps of organs and flesh and odd tufts of hair clinging to a bone structure. The stench is even worse than the appearance. It is a mixture of every repulsive odor in the world—excrement, rotted meat, swamp water, urine—and invades the sinuses by full frontal assault, as though penetrating through the bones of the face. One reacts with a deepseatedrevulsion. The neck hairs jump to a state of alarm, and the nervous system sends out a message to flee. It is an olfactory memory not easily forgotten.

Lacassagne had stopped noticing those sensations, having performed hundreds of autopsies, often in hot, unventilated conditions. The only complaint he and his colleagues sometimes voiced was that the smell on their fingers would linger for days.

Lacassagne liked to use aphorisms in teaching. A favorite was: “A bun-gled autopsy cannot be redone,” emphasizing the need for care and precision. Bernard must have dozed through that lesson, judging by the state of the cadaver. He had examined the brain, as recommended, but in order to reach it, he’d smashed off the top of the head with a hammer—not with a saw, as his mentor had taught—eliminating any chance of detecting head trauma. He’d opened the chest with a chisel, as prescribed, but completely destroyed the sternum, making it impossible to see if there had been a traumatic chest injury. The organs had been removed and placed in a basket. Many bones were out of place. No matter—the master would work with whatever materials he had. First he needed to determine the victim’s age. There were several places he would normally have looked to make an estimate. The junctions of the skull bones would have been one, if they had not been rendered useless by the hammer blows. Instead, he directed his attention to the pelvis. He examined the junctions between the sacrum—the triangular structure that contains the base of the spine—and the hip bones on either side of it. Those junctions are obvious in a child and progressively become fused as a person reaches adulthood. He also examined the fibrous junctions among the last few vertebrae in the coccyx, which also become fused over the years. Lacassagne examined the victim’s jaws and teeth. The teeth were in good shape, but years of gingivitis had caused a loss of bone around the tooth sockets. The bone of the tooth sockets, normally well defined and sharp at the edges, had resorbed into itself and presented a ratty appearance. The state of all those age-related changes characterized a person between forty-five and fifty years old—not thirty-five to forty-five, as Bernard had stated.

The next step was to determine the victim’s height. Standard practice at the time was to stretch out the cadaver and add four centimeters (one and a half inches) to roughly account for the loss of connective tissue. But that was too inaccurate for Lacassagne. Instead, he made use of the newly developing field of anthropometrics—the statistical study of body dimensions. Researchers had been experimenting with methods of deducing the size of a body from individual bones, but no one had done the kind of comprehensive studies that would make their correlations precise and authoritative. Lacassagne knew about this shortcoming, so he assigned Étienne Rollet to write a thesis on the relationship between certain bones of the skeleton and the length of the body. Over the years, Rollet obtained the cadavers of fifty men and fifty women and measured more than fifteen hundred bones, down to the millimeter. He focused on the six largest bones, including the three bones of the upper and lower leg (the femur, tibia, and fibula) and the three of the upper and lower arm (the humerus, radial, and ulna). He carefully charted the bone lengths of men and women—right-handed and left-handed people of various ages. As he recorded and charted hundreds of measurements, Rollet began to see certain regularities. Within a given gender and race and general age cohort, the length of individual long bones of the skeleton bore a constant correlation to the overall body length. For example, a man’s thighbone measuring 43.7 centimeters (1 foot, 5 inches) corresponded to a body height of 1.6 meters (5 feet, 3 inches). If his upper arm measured 35.2 centimeters (1 foot, 2 inches), he probably stood at 1.8 meters (5 feet,11 inches).

The findings were so predictable and consistent that Rollet realized he could create a forensic tool. He compiled two charts—one for men, one for women—with six columns for bone lengths and one for the overall calculated body length. By looking up the size of any of the six major bones, a doctor could move his eye across the chart and estimate the length of the entire body. The chart had limited accuracy, however: The thighbone lengths, for example, increased in increments of six centimeters, and the overall body lengths by increments of two. To make the estimates more precise, Rollet developed a simple mathematical equation that would increase the accuracy to within half a centimeter. The method seemed almost too simple; yet he tested the procedure on several cadavers, including that of a recently executed criminal, and found it quite precise.

Lacassagne consulted his student’s chart as he cleaned away the flesh that remained on the cadaver’s arm and leg bones. Because he had an entire cadaver with all six major bones available, not just a few, as often was the case, Lacassagne could double- and triple-check his results. He averaged the numbers to estimate a body height of five feet eight inches. Bernard’s estimate had been about an inch and a half shorter.

Gouffé’s family was unsure about his exact height, so Inspector Goron telephoned the victim’s tailor and the military authorities in Paris, who had measured him at his time of conscription. Both agreed: He was five feet eight. Further measurements and other calculations told Lacassagne that the victim had weighed about 176 pounds—again a match to Gouffé. Now for the hair. One of the key reasons that Bernard and Gouffé’s brother-in-law had failed to identify the cadaver was that Gouffé’s hair was chestnut brown and the cadaver’s was black. Lacassagne asked Goron to order his men to go to Gouffé’s apartment in Paris, find his hairbrush, and send it by courier to Lyon. Lacassagne could see that the hair from the brush was chestnut in color, just as Gouffé’s relatives had described. Then Lacassagne took the bits of black hair that remained on the cadaver and washed them repeatedly. After several vigorous rinsings, the grimy black coating that had built up from putrefaction dissolved, revealing the same chestnut color as the hair from the brush. To make sure the hair color was natural, Lacassagne gave samples to a colleague, Professor Hugounenq, a chemist, who tested them for every known hair dye. He found none. Next, Lacassagne microscopically compared the hair samples from the brush with those from the cadaver’s head. The samples all measured about 0.13 millimeters in diameter.

That would have been enough for most medical examiners: the victim’s age, height, approximate weight, hair color, and tooth pattern. But it was not enough detail for Lacassagne, who taught that “one must know how to doubt.” He had seen too many errors by medical experts who had fit most pieces into place but not all of them. And so he pushed on. In the days before DNA testing, nothing could rival a fresh cadaver for an accurate identification. A fresh body would reveal facial features and identifying marks, such as scars and tattoos. Relatives could be called to identify the cadaver, which is why morgues at the time included exhibit halls. And yet skin, the great revealer of identity, concealed certain aspects of identity, as well. Skin could erase history. An old injury, such as a bone break or deformity, would exhibit no trace in the healed-over skin. Bones, on the other hand, were “a witness more certain and durable” than skin, wrote Lacassagne. Long after the soft tissues had decayed, the bones would remain just as they had been in the moment of death. So with little more than bones and gristle to work with, he searched for whatever history those bones might portray. He spent hours scraping bits of flesh off the skeleton, examining the points where ligaments connected, measuring bone size, and opening the joints. Something drew his eye to the right heel and anklebones. They were a darker brown than the bones around them. He cut away the tendons that held the two bones together and examined the inner surfaces of the joint. Unlike the clean and polished surfaces of a healthy joint, these bone ends were “grainy, coarse, and dented”—signs of an old injury that had improperly healed. The ankle could not have articulated very well. The victim probably had limped.

Moving forward on the foot, he examined the joint between the bone of the big toe and the metatarsal bone. The end of the metatarsal bone had accrued a bony ridge, which extended clear across the joint and butted into the toe bone. The victim would not have been able to bend his right big toe. Lacassagne suspected that the victim had gout, a disease in which the body loses the ability to break down uric acid. Over time, the chemical accumulates as crystals in the joints, particularly the big toe. In advanced cases, the bone ends build up a chalky deposit, sometimes enough to painfully immobilize a joint.

Lacassagne worked his way up the right lower leg. The fibula, the narrow bone running alongside the calf bone, appeared slimmer than that of the left leg. This meant that the muscle must have been weakened, for without the pull and pressure exerted by muscles, the bones beneath would lose mass. The right kneecap was smaller than the left and more rounded. The interior surface of the kneecap showed several small bony protuberances. None of these features previously had been noticed because the first examination took place three weeks after death. At that stage, both legs could have been bloated with gas. It was only now, with the skin and muscles removed, that this aspect of the victim’s medical history was revealed.

To confirm his observations, Lacassagne called Dr. Gabriel Mondan, chief of surgery at the world-famous Ollier clinic in Lyon. Mondan carefully studied the leg and foot bones, sketching their irregularities, treating them with chemicals to remove the bits of flesh, and drying and weighing them. He found that the bones of the right foot and leg weighed slightly less than those of the left, individually and collectively. He confirmed Lacassagne’s observation of the kneecap, and of the subtle withering of the lower part of the right leg. He noted that the right heel and anklebones were “slightly stunted.” He placed both sets of bones on a table. The bones of the left foot sat normally, with the anklebone, or talus, balanced on the heel. The anklebone of the right foot kept falling off.

Meanwhile, in Paris, Goron’s men had been gathering information about Gouffé. They interviewed Gouffé’s father, who recalled that when his son was a toddler he fell off a pile of rocks and fractured his ankle. It never healed correctly. Ever since then he’d dragged his right leg a bit when he walked, although many people did not notice. Gouffé’s cobbler testified that whenever he made shoes for him, he made the right shoe with an extra-wide heel and used extremely soft leather to accommodate his tender ankle and gouty toes. “His big toe stuck up when he walked,” the cobbler said.

Gouffé’s physician, a Dr. Hervieux of Paris, attested to a variety of leg problems that had plagued his patient for years. In 1885, Hervieux treated him for a swelling of the right knee. The condition had been chronic, Hervieux reported: Another doctor had considered amputating the leg. Hervieux instead prescribed two months of bed rest, after which Gouffé returned to work. In 1887, Hervieux saw his patient for a severe case of gout in the big toe of his right foot. This, too, was a chronic condition, he said, and caused so much painful swelling that Gouffé could not bend the toe joint. Hervieux sent his patient to a spa at Aix-les-Bains for six weeks. A document from the spa stated that Gouffé had suffered a relapse in 1888.

By now, enough evidence had accumulated for Lacassagne to satisfy even his doubts. The victim had been five feet, eight inches tall, weighed 176 pounds, and was about fifty years old. He had chestnut-colored hair and a complete set of teeth, except for the first upper molar on the right. The man had been a smoker —Lacassagne surmised that from the blackened front surfaces of the incisors and canine teeth. Sometime in childhood, the victim had broken his right ankle, an injury that had never properly healed. Later in life, he had suffered several attacks of gout. He had also had a history of arthritic inflammations of the right knee. All these injuries had contributed to a general weakening of the victim’s lower right leg, reflected in the reduction of bone mass. He must have frequently suffered pain in that leg and perhaps walked with a slight limp. “Now we can conclude a positive identity,” Lacassagne reported. “The body found in Millery indeed is the corpse of Monsieur Gouffé.”

Once the body had been identified, the pieces of the case quickly fell together. Goron had a replica of the trunk made and displayed it in the Paris morgue. It caused a sensation: Within three days, 25,000 people had filed past it, one of whom identified it as having come from a particular trunk maker on Euston Road in London. Goron traveled to London and obtained the receipt, which showed that the trunk had been purchased a few weeks before the crime by a man named Michel Eyraud. Goron quickly sent bulletins with descriptions of both Eyraud and Bompard to French government offices on both sides of the Atlantic. He dispatched agents to North America, who followed the couple to New York, Quebec, Vancouver, and San Francisco—always just a few days behind them.

Finally, in May 1890, a Frenchman living in Havana recognized Eyraud and alerted Cuban police. His girlfriend, meanwhile, had stayed in Vancouver, where she met and fell in love with an American adventurer. Eventually, he persuaded her to turn herself in.

With both suspects in custody, the bizarre story of the crime emerged. Bompard and Eyraud had known of Gouffé’s wealth and reputation for sexual adventure, and they’d heard that he spent most Friday nights at the Brasserie Gutenberg after emptying his office safe. So they had set a trap.

Eyraud went to Bompard’s apartment, where he attached an iron ring to the ceiling in an alcove behind her divan. He passed a sturdy rope through the ring, then hid the apparatus and himself behind a curtain. Bompard, meanwhile, went to the café, found Gouffé, and started flirting with him. She persuaded him to go back to her apartment, where she took off her clothes and slipped into a robe. Seductively drawing Gouffé close to her, she playfully slipped the sash around his throat. She passed the ends to Eyraud, who affixed them to the rope and, pulling with all his might, hanged Gouffé before he could react. To their horror, however, when they rifled his pockets, they found that he had left all his money behind somewhere.

They needed to get rid of the body, and fast. They trussed it up in a canvas sack, packed it in a trunk, and bought tickets on the next morning’s train to Lyon. Once in Lyon, they spent a night in a rooming house with the body, then rented a horse-drawn carriage to travel into the countryside.

They rode about a dozen miles south of the city, then dumped the body on a steep hill leading down to the Rhône River. On the return trip, Eyraud purchased a hammer, smashed up the trunk, and threw the pieces in the woods.

They had expected the body to roll into the river and float downstream, never to be seen again. Unfortunately for them, it got hung up in a bush and became the key piece of evidence that led to their convictions. The world saw it as a miraculous turn of events, and Lacassagne as the wizard who had made it happen. The feat was unprecedented. To think that the corpse had been autopsied and buried for months! Not even Gouffé’s relatives could identify it. But Lacassagne, using the tools of a new science, enabled the victim to exact justice from beyond the grave. “It was no miracle,” his former student Locard protested, “because modern science is contrary to miracles.” Yet as a work of deduction, it was truly “a masterpiece—the most astonishing, I think, that ever had been made in criminology.”

After a massively attended and publicized trial, Eyraud received the death penalty and Bompard was sentenced to twenty years in prison. On Feburary 4, 1891, Eyraud went to the guillotine. Thousands of people mobbed the event, straining to glimpse the notorious killer. Street vendors circulated among them, selling miniature replicas of the infamous trunk. Inside each was a toy metal corpse bearing the inscription “the Gouffé Affair.”

Excerpted from The Killer of Little Shepherds by Douglas Starr Copyright © 2010 by Douglas Starr. Excerpted by permission of Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

This segment aired on November 16, 2010.