Advertisement

At 50, The Cape Cod National Seashore Is Literally Washing Away

Resume

The Cape Cod National Seashore turns 50 on Sunday.

On Aug. 7, 1961, President Kennedy signed a law preserving most of the Atlantic coastline of the outer Cape as national parkland and roping it off from development forever.

But of course, in nature, nothing is forever. Despite its protected status, the great beach is on borrowed time.

A Big Pile Of Sand

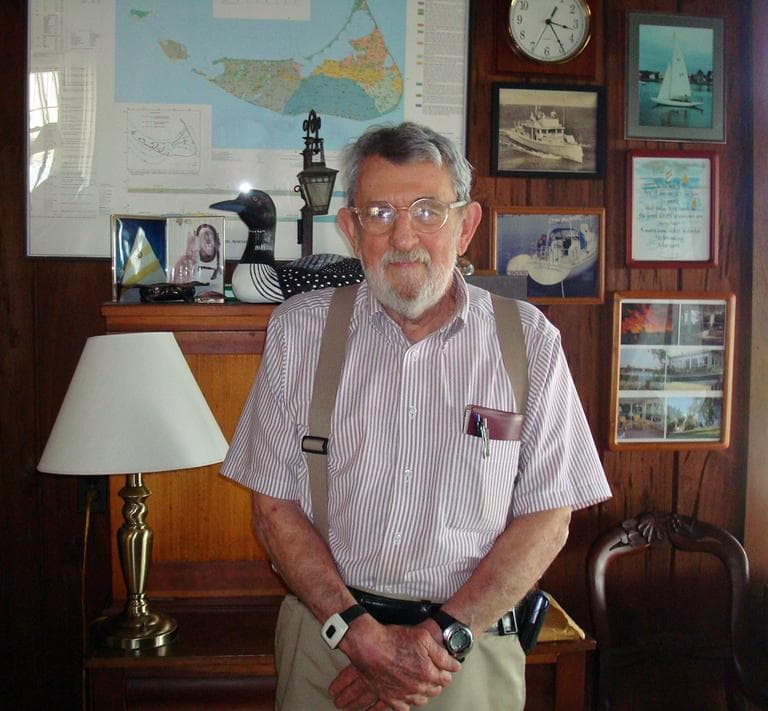

Sitting in his sun room in North Falmouth, Robert Oldale's home is festooned with maps and other artifacts of his 40 years with the U.S. Geological Survey. He literally wrote the book [PDF] on Cape Cod and he describes the Cape as a geologic flash-in-the-pan: a land mass with a lifespan more akin to that of a mosquito than a elephant.

"It's made up of mostly sand that was deposited by the last glacier that was in here, and that glacier got here somewhere around 23,000 years ago, and then left about 20,000 years ago," Oldale says.

"We're sitting on a big pile of sand, and the important part about that is that it is unconsolidated, in other words, the grains are not stuck together," Oldale explains. "Now a deposit made of dry sand grains has absolutely no resistance to wave attack."

The Shoreline Keeps Moving

At Nauset Light Beach in Eastham, Mark Adams points to a lighthouse that had to be moved back from its perch on the bluffs in the 1990s.

Adams is the geographic information systems (GIS) specialist for the Cape Cod National Seashore. There's a lot of work for a mapmaker out here, because the shoreline keeps moving.

It has retreated an average of three feet per year for as long as anyone's been keeping records, which is why the namesake lighthouse at Nauset Beach had to be moved back.

"Personally I've been here about 20 years. If you multiply three feet by 20 years, that's 60 feet of the bluff that's disappeared," Adams says.

That means the bluff appears noticeably different to him.

"It's not really a loss," Adams says. "There's nothing sad about it because it's part of a dynamic process, where it's contributing to the growth of land somewhere else."

It's All Going Under

"All of Provincetown owes its existence to the rise in sea level and the erosion of the glacial cape," Oldale says.

He says the angle of wave attack is constantly grabbing sand from the elbow of the Cape and pushing it up to the fist. Chatham and Orleans shrink, while Provincetown grows.

It sounds like a process of constant renewal, but there's a catch.

"If you take a sand grain that's eroded from the cliff face, it has one-third of a chance of coming back above sea level and creating a landmass," Oldale says. "Two-thirds of the grains will just stay below sea level."

In other words, it's a net loss. Grain by grain, year by year, it's all going under.

How fast is a matter of debate, but that's nature. And the establishment of the Cape Cod National Seashore, 50 years ago, has allowed erosion along the outer beach to proceed unabated.

On The Edge

On Nauset Light Beach, a big yellow house sits right up against the bluff.

"There are many houses in the seashore that are private," Adams explains. "Anyone who had a property that was developed before 1959 was allowed to keep that house."

But this house is about 30 feet off the bluff. That means it has about 10 years left, statistically speaking.

"And you really want to remove it long before it's on the edge," Adam says.

Houses like this one are a personal bugaboo for Oldale.

"When they created the National Seashore, what we should have done was throw everybody off," Oldale says. "Because it's gonna go, you can't stop it."

Oldale corrects himself.

"There is one way to stop it. We could armor this coastline," Oldale says. "It'll look horrible, it would be a cement or riprap, 10 to 15 feet high, all the way around the Cape."

"There’s nothing sad about [erosion] because it’s part of a dynamic process, where it’s contributing to the growth of land somewhere else.”

Mark Adams, geographic information systems specialist

Which of course would not be allowed, and Oldale says that's just fine with him.

"It's owned by the people. It can erode and it isn't going to bother anybody," Oldale says.

A Shadow Of Uncertainty

Oldale says the whole Cape will be reduced to a few scattered islands and shoals in about 2,000 years — half a blink in geologic time.

But there is a wild card in all of this: climate change.

"There's a wide range of predictions about how sea level rise might be accelerating," Adams explains.

The background rate of sea level rise in New England is about three millimeters per year, but melting ice caps and thermal expansion of the ocean could double, triple, or quadruple that rate, Adams says.

"Basically, that's adding inches and feet on top of what we already know about coastal change."

And that, Adams says, is what casts a shadow of uncertainty over the future of the Cape Cod National Seashore, in its next 50 years, and beyond.

This program aired on August 5, 2011.