Advertisement

Author Conversation: Dr. Nick Trout On 'Ever By My Side'

Here's a question to consider. How much did Americans spend on veterinary care for their pets last year?

The answer: More than $12 billion. That's on medicines, treatments, surgeries and diagnostic technologies that rival equipment used on human patients.

In a way, the ever growing expanse and expense of animal medical care puts vets themselves in a difficult situation. They treat beloved pets. But can they truly understand the love that drives a person to push for treatment at any cost, even if it comes at a high cost to the animal's comfort?

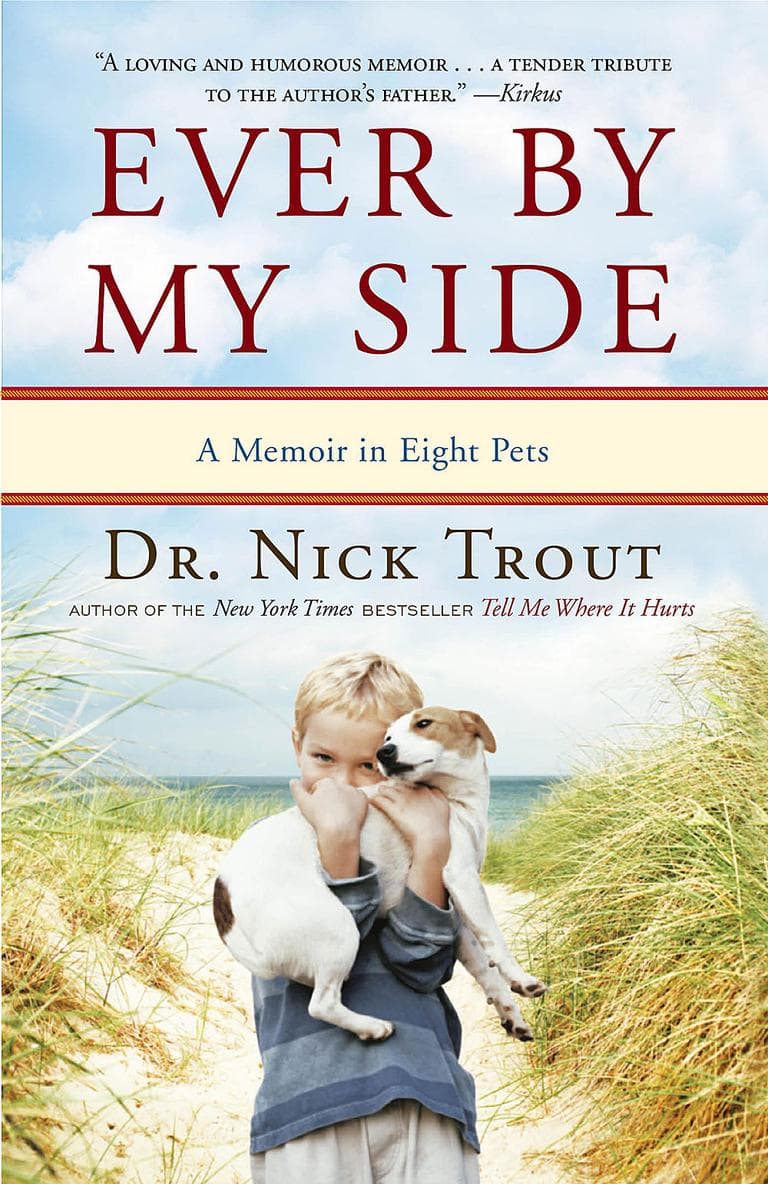

Dr. Nick Trout took up that question by looking at how his own pets have shaped his life. Trout is a staff surgeon at the Angell Animal Medical Center in Boston. We talked about his book: "Ever By My Side: A Memoir in Eight Pets" when I visited Angell's state of the art animal hospital.

Guest:

- Nick Trout, veterinarian and author of Ever By My Side: A Memoir in Eight Pets.

Excerpt: "Ever By My Side: A Memoir in Eight Pets"

AUTHOR’S NOTE

AUTHOR’S NOTEFor more than twenty years I have worked as a veterinarian, blessed with the responsibility of caring for sick animals and in doing so, granted unprecedented access into the unique and powerful bonds between humans and their pets. In my professional life I am constantly striving to make a connection with owner and animal alike and it is always a delicate balancing act. I want the other human in this our triangular relationship to realize that I am sensitive but not too sappy, that I am intrigued but not prying, that I can be objective and scientific but more than prepared to share my own experiences and philosophies. Most of all I want them to see that I understand why they seek my help. I know what motivates their desire to restore their pet to full health. I know what an animal can do for a lonely soul, a family, a broken heart, and an angry state of mind. I know the power of the stuff that cannot be put into words and I won’t ask them to try, because I want them to understand that I get it.

Advertisement

I imagine my life has been similar to those of most people— stuff happens, we make choices, we take a certain path, and many of the decisions we make depend upon the lessons we learned along the way and how we interpreted their meaning. To my way of thinking it’s like bumper stickers on the back of a clunker—you choose the stickers that reflect your personality and the more you accumulate, the better the guy driving the car behind gets to appreciate the kind of person you really are. I’ve been fortunate enough to spend most of my life around animals, the creatures I have come to think of as my own pets. Each and every one of them has played their part in bringing me to this point. In their own unique way, they have all donated a bumper sticker or two, their message catchy, simple, and above all else, honest.

This book is based on my own recollections of these personal pets (and many more besides) with occasional input and insight from members of my family. In some instances the names and identifiers of individuals central to the story have been changed to maintain anonymity. The result is perhaps less memoir than discerning retrospective, as I take an opportunity to relive a few of the defining moments throughout my life in which animals took their cue, stepped up, and gave me a chance to appreciate a different perspective. This is my attempt to show them off and share their subtle, startling, and inspirational lessons, which have played a small but vital part in helping to shape the person you see with the stethoscope around his neck. As you read on, I truly hope my interpretation of their significance will resonate, will induce a knowing smile, a nod, and maybe a wayward tear, as you too recognize the powerful benefits of the animals in your own life.

Part One

U N I O N J AC K

1.The Definition of Different

I wish I could tell you I have enjoyed the company of a dog or a cat every day of my life, but it’s simply not true. In fact, my earliest appreciation of pets in any form did not occur until I was four and, even then, was limited to my grandmothers’ dogs.

My mother’s mother possessed a white male toy poodle named Marty. From the start, Marty made it abundantly clear that he had no patience for small curious hands, except perhaps as chew toys. Venture into his territory, that is, anywhere within an invisible fifty-yard perimeter of my grandma’s house, and he would come at you, bouncing forward as if his legs were little pogo sticks, emitting a bark that could crack bulletproof glass, before scurrying away to safety behind grandma’s ankle, only to repeat the process over and over again until he finally ascended into her arms. From this lofty position he could look down at me with an expression that said “If you bother me, I will make you pay in blood and tears.”

Marty was not even a year old and his presence had already ne- gated what few pleasures there were after a two-hour car drive to visit my grandma.

“Sit you down while I put the kettle on,” Gran would say as everyone rushed for a vacant seat in a game of musical chairs that invariably left me with the sofa where Marty had settled. Curled up on the middle cushion, Marty would emit a throaty, malicious grumble if I so much as inched toward the ends of the couch.

There was also the smell. The entire house reeked of the only food Marty deigned to consume—sausages! I never once saw him eat regular dog food. And I’m not talking about classic British bangers. Marty’s delicate mouth and discriminating palate preferred, no, insisted upon, a small, handcrafted breakfast sausage from a local butcher that had to be fried, allowed to cool, and then carefully chopped into congealed mouth-size pieces. At some point during every visit Gran would excuse herself, go to the kitchen, take up a position next to the stove, and disappear into an oily cloud as she seared sheathed meat that crackled and spat in her direction. I would look over at her and she would smile the smile of old people everywhere, content to check off another comforting chore in her daily routine. Meanwhile Marty might squirm a little on his throne and sigh, not out of boredom, but approval, pleased the hired help was doing his bidding.

Neither my grandma nor my parents ever suggested Marty and I become acquainted or that Marty become socialized around children or that he be reprimanded for his bad manners. Perhaps I couldn’t be trusted not to pinch, yank, rip, or snap as I did with most of my toys. Perhaps they didn’t want to take any chances. Whatever the reason, I kept my distance, painfully curious to discover the feel of his hypoallergenic, steel-wool fur but convinced he would practically explode if I so much as touched him. After a while, I lost all interest in Marty. What was the point? How could I have a relationship with an animal who might as well have been behind bars in a zoo? I couldn’t understand what anyone saw in a pet you couldn’t, well, pet.

On the other hand, my grandmother on my father’s side had a placid female Dalmatian named Cleo and to my delight (and no doubt to the delight of my mother), they occupied a small bungalow next door to our house. In contrast to Marty, Cleo could be completely trusted around children. She was tolerant and forgiving and endowed with seal-pup insulation that possessed a certain . . . give, similar to a Tempur-Pedic foam mattress. Cleo never tired of me petting her, happy to relinquish her short, fine hairs to my sticky palms, which would soon resemble a pair of black and white mittens. I could fall over her or fall into her and she would either lie there and take it, indifferent to the contact, or rise quickly to her feet and find somewhere else to lie down, as though she was sorry for getting under foot rather than angry at being disturbed. At the time, my little sister, Fiona, was too small to play with me, so I was thrilled to share our backyard with a big old spotty dog who never once regarded me as though I were a tasty hors d’oeuvre.

To fully appreciate the bond that formed between me and Cleo, you have to understand our shared interest in swallowing inanimate objects and to help you do so I must mention a chilling yet formative recollection from my childhood.

Late one night, barefoot and immersed in oversized cotton pajamas, this four-year-old boy stood alone in the kitchen having snuck out of bed in search of a snack and a glass of milk. I have always been partial to yogurt, methodically working my way to the bottom of the carton, scraping every last pink glob of strawberry-colored additives off the plastic and onto my spoon. Even now I can recall the feel of that particular spoon, cool and smooth and small, like a silver christening spoon, satisfyingly tinkly on my deciduous teeth and almost weightless in my mouth. With the yogurt gone and my mind in a dull and dreamy state, I began playing with the spoon in the back of my mouth, appreciating the metallic sensation way back on my tongue and how it was possible to push it a little farther and induce gagging, a sharp and forceful contraction deep in my belly—until somewhere just beyond this point, the reflex of actual swallowing took over, involuntary and, to my horror, completely irreversible. I felt the tiny handle leaving my fingertips and slipping from my grasp, and suddenly, like the yogurt, the spoon was gone, disappearing deep inside my body.

When I felt it go there was no pain or discomfort, only the rush of fear that I had done something very wrong and, perhaps more important, impossible to justify. I mean you don’t just swallow a spoon by accident. What was I going to tell my mum and dad? I fell on a spoon while my mouth was open! I was so hungry I ate my yogurt, spoon and all!

I waited for a few minutes and nothing happened. I had a drink of milk and nothing happened. I didn’t feel any different. If I jumped up and down nothing rattled inside my body, nothing tickled or poked through my skin. In the end, instead of confessing my sin to my parents, I decided to wait and see what, if anything happened and besides, I was tired, so I went back to bed.

At this early stage of my life, I’m not entirely sure I could make any connection between what went into my mouth and what came out the other end. All I knew was that by the next morning I still felt fine. No one seemed to have noticed there was anything miss- ing from the cutlery drawer and so I decided to keep my acquisition of a foreign body a secret, comfortable with the notion that the little spoon was lost inside me, hidden somewhere dark and warm and safe, not causing me any harm, inert and happy to simply hang out. It was not until I was thirteen years old, and clearly not much wiser, that I feared my secret would be revealed.

In trying to define my early teenage stature, some might use the word lean out of kindness. Truth be told, I was a scrawny whippet of a boy. I was, however, blessed with a semblance of speed, a characteristic that did not go unnoticed by our school sports teacher, Mr. French.

“All you have to do is catch the ball and run for the line.” Sounded simple enough, but his synopsis of what would be required of me as a winger on our school rugby team failed to do justice to the rough and tumble of what the game meant to boys with far more muscle, spite, and testosterone.

I like to remember the critical moment in terms of the dying seconds of a crucial game, perhaps a grudge match against local rivals or a match to claim a league championship title, with time running out and one more try needed to win—me making an impossible catch, a shimmy left, a fake right, defenders falling at my feet as I charged for the line, rugby ball tucked tight and safe in my chest as I leapt over giants and landed for my winning points just as the final whistle blew. What actually transpired was that I caught a ball in the middle of the field and hesitated, and in a moment of panic half a dozen boys jumped on top of me, frozen mud on the right side of my body, hundreds of pounds of grunting, writhing, sweaty bodies on my left. Something had to give as a result of this mayhem and unfortunately that something happened to be my breastbone.

Advertisement

I’d be lying if I said there was an enormous crack akin to a shot- gun blast. In fact I got up and carried on playing. All I noticed was an increased difficulty in breathing and by the end of the game it was obvious that this was more than a general lack of physical fitness on my part.

And so I found myself in an emergency room hearing a young doctor suggest that I get a chest X-ray and realizing that for the first time since swallowing that fateful spoon, I would be the recipient of a test that would surely unmask my embarrassing silverware secret.

“You know, Dad, I think I’m feeling better. It’s probably nothing,” I said to my father, convinced that after all these years the spoon was somehow still sitting in my stomach or casually leaning into the side of my esophagus, minding its own business.

When the doctor emerged with the images, I braced for the ramifications of their peculiar and unequivocal revelation.

“Well, guess what I found hidden in his chest?”

I knew it. The X-ray machine was just another type of camera and I knew how a camera never lies.

“See this dark line, here. That’s a crack, a fracture. Your son has broken his sternum.”

I looked at the black-and-white film for myself, not at the break, but all over the image, looking for something metallic, white, and vaguely spoon shaped. But there was nothing.

It wasn’t until I studied biology in school and ultimately medi- cine at college that I realized the stupidity of worrying over a chest X-ray. They would have had to take an X-ray of my lower abdomen. I’m sure this is where that pesky spoon is still lurking to this day.

But let’s get back to Cleo, to the two of us in our backyard, my green universe, playing endless rounds of fetch with her favorite ball.

For a while the game proceeded as expected—slimy ball, pain- fully short throws from an uncoordinated little pitching arm, patient soft-mouthed dog politely performing retrieval exercises. Then I noticed something long and thin and obviously amiss dangling from the base of Cleo’s tail and trailing behind her. She took a time-out, intermittently squatting, straining, and dancing around as if she had a length of unshakable toilet paper stuck to her foot. She was visibly upset and unable to continue our game. If I had to put an emotional label on her behavior I would say she appeared to be embarrassed.

Concerned and curious, I ran to the house to fetch my father, insisting he come and check out Cleo.

“Look,” I said, all business as I pointed toward the aberration. “There’s something up her bum!”

Dad greeted Cleo with a pat to her head before shuffling around behind her, nodding his agreement.

“It’s okay, son. It’s one of Gran’s old nylon stockings.” I was puzzled and a little upset.

“Why would Gran stick a stocking up Cleo’s bum?” I asked. “She didn’t,” said my father.

“Then who did?” I said.

My father hesitated, deliberated, and ultimately opted for a time- honored adult approach to my line of questioning, that is, he ignored it.

“Let’s just give Cleo a few minutes in private. See if she sorts herself out.”

Dad took me by the hand and we backed off, retreating several yards before he squatted down by my side and whispered, “We’ll watch her from here.”

“But why is it coming out of her bum?” I whispered back.

He considered me with what I would later recognize as a mixture of pride and frustration for being such a relentless little bugger when it came to my wanting to figure out the ways of the world.

“Because she swallowed it,” he said, trying his best to tamp down the curt edge creeping into his voice. “Because Cleo likes to eat things she shouldn’t. Things that aren’t good for her. Things other than dog food. Things like Gran’s underwear. But don’t you worry, no matter what your Cleo eats it always comes out the other end.”

Here was my first lesson in basic gastrointestinal physiology, that according to my father, what goes in, must come out. Of course I was potty-trained and more than capable of taking myself off to our bathroom alone, but this was the first time I recall a clarification of the cause-and-effect relationship between ingestion and elimination. What I really needed to know was whether, during inappropriate dining, Cleo had ever swallowed a spoon. If her current discomfort was anything to go by, surely I would have noticed when a firm metallic object found its way out?

My father must have misread the confusion and anxiety playing across my face and tried to placate me by adding the word “Eventually.”

It didn’t work.

We waited for what felt like three hours but was probably more like three minutes and watched as Cleo spun around and around, scooting her rear along the grass in vain, clearly becoming more and more frustrated.

“I’ve got an idea,” my father said, standing up and heading back toward Cleo. “Go grab her ball.”

I did as I was told and reported for duty.

“Now, when I’m ready, I want you to throw Cleo’s ball as far away as possible.”

I didn’t understand. “Why?”

“You’ll see,” he said.

Another adult response all inquisitive children despise because obviously I didn’t see and that was why I was asking the question in the first place.

“But I can’t throw very far.”

My father insisted that this wouldn’t matter (alternatively, he may have said, “Just shut up and do as you’re told”) and stood a short distance behind Cleo after placing me and the ball in my hand at her head.

“Hold on a moment, son,” he said, watching and waiting as Cleo forgot about her troubles, focused on the ball, and tried to anticipate which way it would go.

At the time I never noticed how my father was placing the sole of his shoe firmly down to the ground, pinning the trailing end of the wayward hosiery in place.

“Now,” he shouted, and with concentration and enough fierce determination to produce a little grunt as I bit down on the tip of my tongue, I released the airy plastic ball from my hand like a shot put, and it landed about three feet away.

Not far but far enough for Cleo to pounce forward, retrieve the ball, and leave the stocking behind, lying on the ground.

Cleo acted as if nothing had happened and plunged right back into our game, dropping the ball at my feet, ready to go again. Just once, she glanced over her shoulder at my father and the stringy, discolored length of nylon before focusing on me, as if she seemed disturbed by what he was doing, as if she would rather he pick up whatever it was that had become stuck to his foot because it was disgusting.

Although I like to chalk this up as my first, if indirect, canine medical intervention, I should point out that this approach to treating Cleo’s protruding foreign body may have seemed rational but was totally inappropriate. My father should have left well alone and sought veterinary advice. What if the stocking had been lodged in Cleo’s small intestines? What if the nylon had cheese-wired through her guts? Fortunately, as it turned out she was lucky, perfectly fine, ready to graze her way through my grandmother’s lingerie once again. It would be decades before I saw the error in our approach to her predicament.

All three of us walked away from the incident as though nothing much had happened. At no time did my father and I dwell on what we had done, on how our ploy had brought about Cleo’s transition from anxious and uncomfortable to oblivious and happy to play. He never paused to ruminate on the moment when the seed of possibility was firmly planted, to recognize the first inkling of his son’s interest in helping sick animals. Within seconds Cleo and I had returned to the carefree rhythm of fetch and my fickle attention had moved on, my pitching arm quick to tire, boredom setting in, and a more pressing question racing to the forefront of my mind.

“Mum,” I shouted, “when will dinner be ready?”

This segment aired on March 1, 2012.