Advertisement

Boston's Key Affordable Housing Program Doesn't Do Enough For City's Neediest, Advocates Say

Resume

Part 2 of a four-part series about affordable housing in Boston. Here are Parts 1, 3 and 4.

Toni Lopes was on her way to Tufts Medical Center in 2015 when something caught her eye. It was a line of people, stretching blocks.

“On Washington Street, down Oak Street, down Harrison Ave.," she says, "and I’m like, ‘Why are all these people here?’ ”

It was a line for a housing lottery. A new building in Boston's Chinatown neighborhood had 95 apartments available for rent for low-income residents. More than 4,000 people reportedly applied.

After seeing the line, Lopes decided to apply. She didn't win the lottery, but she is inching up the waitlist.

“I got a letter back from them in November 2017 saying I was 53 on the list," she says. "I have not received anything since then."

For now, Lopes is doubled up with her brother in the South End. She's retired and living on a fixed income. She can’t afford a place of her own in the neighborhood unless she wins the housing lottery.

Like what you're reading? You can get the latest economic news (and other stories Boston is talking about) sent directly to your inbox with the WBUR Today newsletter. Subscribe here.

A couple of neighborhoods over, in South Boston, Kristen McCart has won the housing lottery — twice.

“Which to me was insane because I’ve never won anything more than a $5 scratch ticket,” she says.

The first win got McCart a small studio in the Seaport. The second got her where she is now: a tidy studio in Southie. She's decorated it with family heirlooms that tell a story about her roots in the neighborhood — like her grandmother's porcelain clown dolls, and her grandfather's bull horns.

"My father’s father was in [World War II] and brought them back for him," McCart says.

McCart's grandparents bought a house in South Boston in the 1940s for $8,000. That's where she grew up; her family was in the downstairs unit, and her grandparents were in the upstairs unit. The house is still in her family.

McCart wanted to stay in the neighborhood. But even with a professional job, she couldn’t afford a place of her own.

“There was nothing below $2,000 a month,” she says. “I’d be eating Cheez-Its to survive.”

Now, McCart pays just under $1,100 for her studio. The market rent for a studio in her building is $2,400.

These lottery units are built through a city policy that requires most new residential developments to contribute affordable housing. Developers have to set aside affordable units in their buildings, build affordable units off-site, or pay into a city fund to build affordable housing — or do some combination of the three.

This policy, known as inclusionary development (IDP) or inclusionary zoning, not only gets affordable units from the private market, but also aims to integrate a mix of incomes in the same building or neighborhood.

Housing advocates, though, say the program is leaving some Bostonians behind.

'Affordable' For Whom?

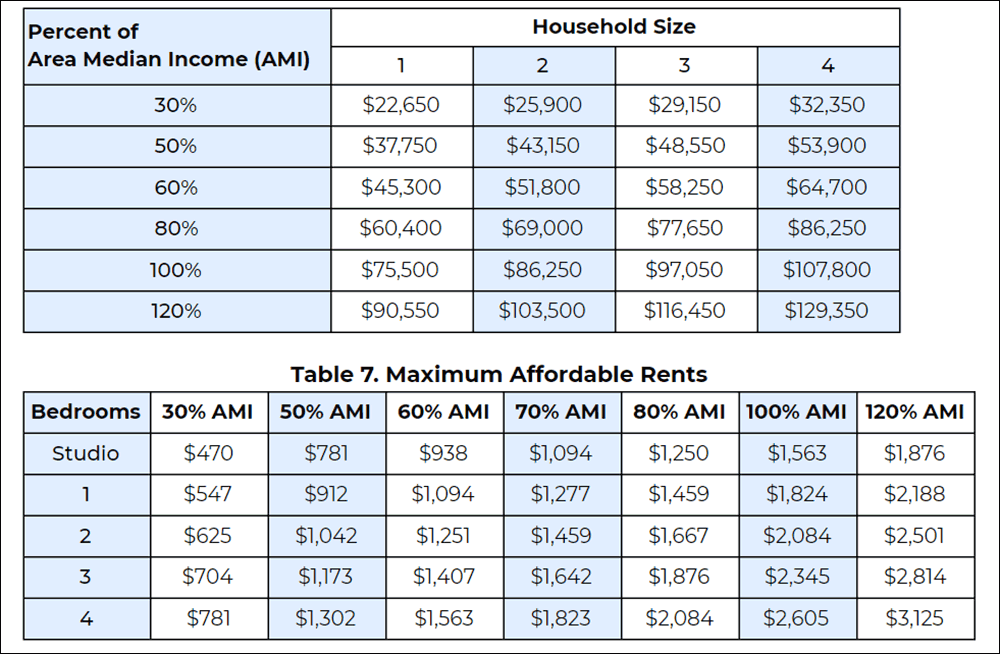

So what is "affordable housing"? Think about it as tiers of affordability. There are moderate-income households, like McCart, and low-income households, like Lopes. IDP is primarily geared toward creating affordable units for moderate-income households. This is because federal and state funding sources generally subsidize low-income housing, but no government subsidy exists for moderate-income housing.

“The traditional funding sources are all focused on lower-income households, and yet there are moderate- to middle-income households being priced out of the city,” says Tim Davis, the Boston Planning and Development Agency's housing policy manager.

He says the city’s policy, which started in 2000, was designed to meet the gap in middle-income housing.

“The quote ‘affordable units’ are not affordable to actual Boston residents."

Kathy Brown, Boston Tenant Coalition

While the city says there are almost 47,000 low-income units in Boston, as Lopes’ experience shows, the demand for this type of housing outstrips the supply.

If low-income residents don’t have affordable units, they are left to the private market. But there are vanishingly few rental units on the private market where low-income households aren’t spending more than a third of their income on rent.

Because of the shortage of affordable units for low-income households, housing advocates say IDP targets the wrong income bracket.

“The quote ‘affordable units’ are not affordable to actual Boston residents,” says Kathy Brown, with the Boston Tenant Coalition.

She argues that the policy doesn't address the housing need for Boston residents most at risk of displacement or eviction.

“People in Boston on fixed incomes or working class have much more limited options,” Brown says.

The city estimates around 34,000 low-income households spend half of their income on rent. These households experience a high risk of housing instability. And the city expects the proportion of low-income residents to grow.

“We think it’s important to lower the income targets for this affordable housing program,” Brown says. “The need is at the lowest incomes. The waiting lists and how many people apply for affordable units, it’s thousands of people. The need is so much greater on the lower end.”

As of 2017, about 1,300 of what the city calls moderate-income rental units have been built. These units are generally integrated into a market-rate building, so lottery winners live in the same building as their market rent-paying neighbors.

For low-income units, it's different. These generally get built through payments made into the city's fund. Since the program started, developers have contributed $137 million, which has been used to build more than 1,000 low-income units. Most of these new low-income units are concentrated in Roxbury and Dorchester.

Finding The Right Mix Of Housing Units

Davis says the BPDA is considering a number of changes to the inclusionary development policy to leverage even more affordability from developers. Right now, IDP only applies to buildings with 10 or more units that also need a zoning variance. But BPDA wants to include more projects, not just those that require zoning relief.

“We think it’s important that every project tries to do something for affordable housing in the city,” Davis says.

Only 13 percent of the units in a building need to be affordable. In a 10-unit building, that's one unit. BPDA is looking into increasing the percentage. And it's evaluating how to target a broader range of incomes with the IDP policy.

Why can't the city just simply tell developers it wants more affordable units and lower income limits? It's a question of feasibility.

“If you can't earn more income than your operating expenses, then you have to put away your toys and go home,” says Peter Roth, the founder of New Atlantic Development, which specializes in mixed-income and affordable buildings.

The addition of affordable units -- by definition below market-rate -- means that developers will lose money on them. But they can't lose too much money. Otherwise the building just won't get built.

“You need to make sure your mix of units — market rate and affordable — will achieve a degree of profitability,” Roth says.

So in exchange for building units at a loss — the affordable ones — the city cuts the developer a deal: zoning relief. Most of Boston's zoning is for short buildings with a small footprint. Zoning relief lets the developer build a larger building with more units. The additional market units make up for the lost profits of the affordable units.

Roth likes the city's policy because it is structured as an incentive for developers while extracting a public benefit from them. However he warns, “It will lose its success if it becomes more like a tax and not an incentive program.”

Longing For A Place Of Her Own

Lopes, the retiree who's living with her brother, is coloring in polka dots on ribbon for her granddaughter's Barbie-themed birthday party.

Lopes grew up in the South End, in the public housing development now known as the Ruth Barkley Apartments. She raised her daughter in the nearby Villa Victoria apartments, a development for low-income households. Her monthly rent for a two-bedroom apartment was under $1,000 for the nearly two decades that she lived there. It allowed her to save for her own home, outside Boston. But during a severe illness, she lost her job and couldn't keep up with the mortgage payments.

“I had to come back to the city. At that point, I didn’t have no other option. Either that or I would have probably been homeless,” Lopes says.

Lopes is one of the many low-income residents waiting for a unit she can afford, in the neighborhood she wants to live in, near her grandkids. She can manage that now, living with her brother. But she longs for a place of her own.

“I would like open space, a large room,” Lopes says. “I’m an artist. I work with acrylic paints, oil paints. I work with floral arrangements, I sew. All of this stuff takes up room.”

This segment aired on February 20, 2019.