Advertisement

Bringing The Forest Into The City: Gina Crandell’s ‘Tree Gardens’

The forest in the city—the notion itself seems an oxymoron. Which is part of the beauty and magic when landscape designers pull it off. It’s the delight of something being in the wrong place at the right time—like greenhouses or big indoor fountains. It’s nature part civilized, and civilization deliciously part wilded in the exchange.

Urban woods and “the exuberance of the forest within compact urban spaces” are the subject of Brookline author and landscape architecture professor Gina Crandell’s new book “Tree Gardens: Architecture and the Forest” (Princeton Architectural Press).

The book combines a brief history with a showcase of contemporary projects. It begins well with the Italian city of Lucca. Beginning in the 13th century, the town erected 21-foot-tall earthen walls around its perimeter to protect it from invaders. Trees were initially planted on the interior side of the wall so that the roots would shore it up. By the mid-18th century, with outside threats faded, allées—or lanes lined with rows of trees on each side—were planted along the top of the walls, turning them into promenades ringing the town and offering views of the surrounding countryside.

From there Crandell takes us to the vast, rigid geometry of 17th century French gardens, using the example of King Louis XIV’s Versailles. This sort of geometry—particularly its expression in Modernist designs since World War II—is ultimately Crandell’s main subject

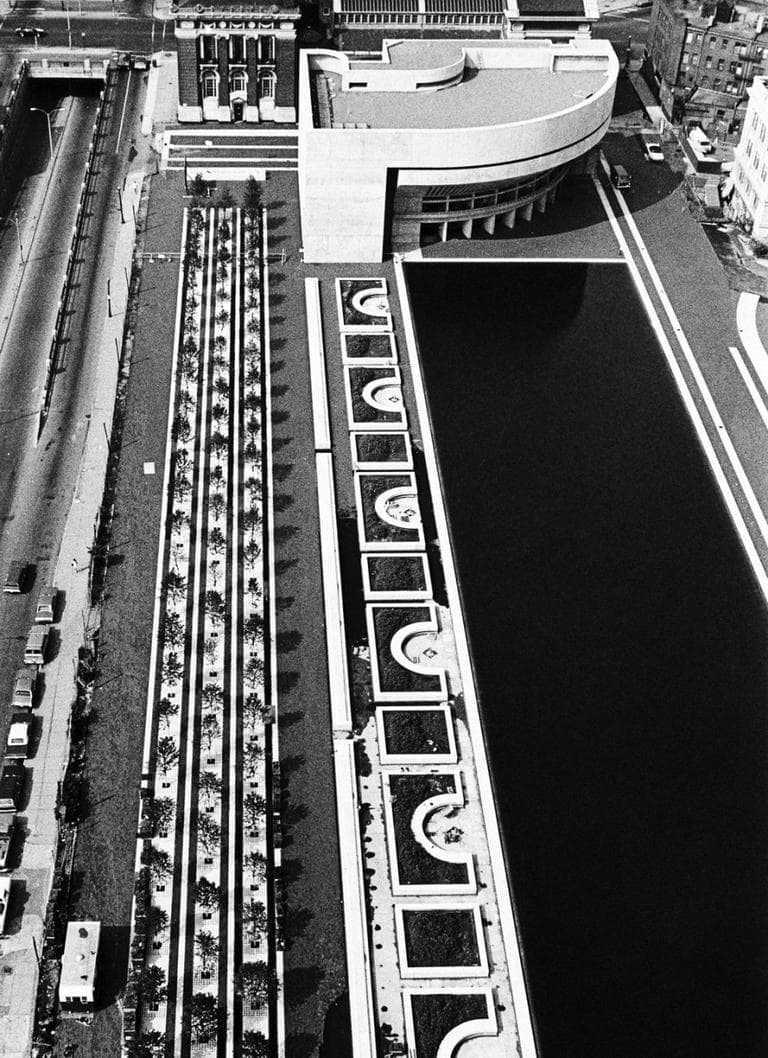

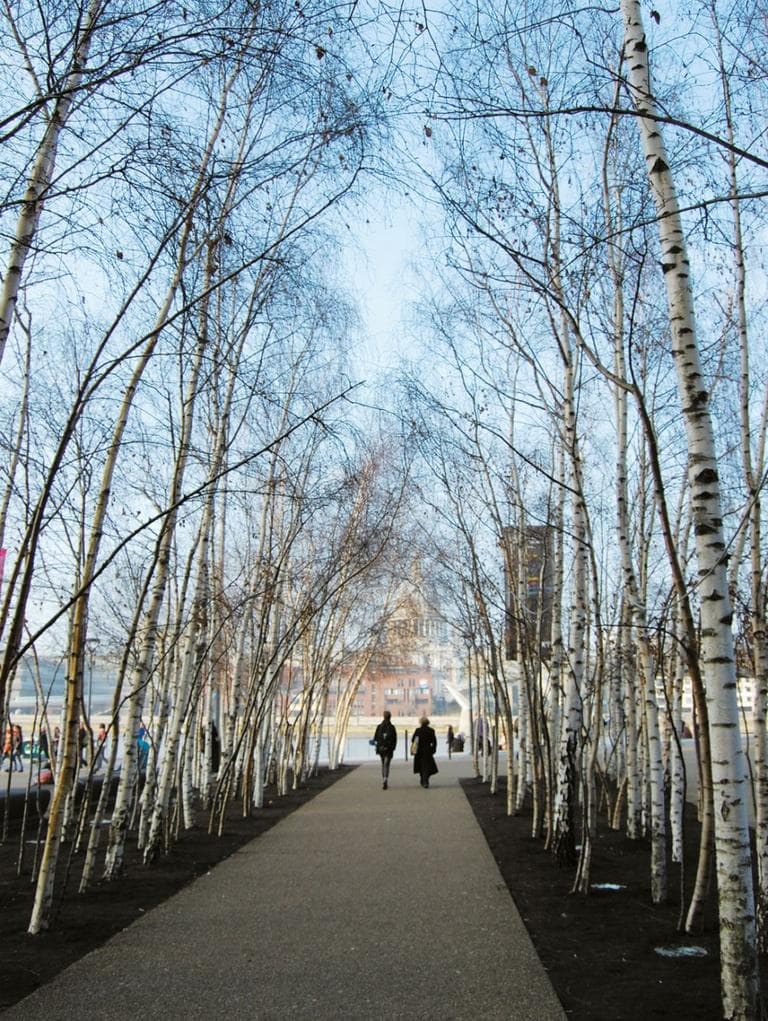

Crandell highlights rows of trees that Sasaki Associates used to frame the edges of the vast concrete Christian Science Plaza in Boston in 1963 (pictured at top). She considers the Swiss firm Kienast Vogt Partner’s rectangular beds randomly filled with birches in its 1995 design for the Tate Modern art museum in London, England; and Beijing firm Turenscape’s 2002 “grid of floating gardens of redwood trees” for the Floating River Gardens at Yongning River Park in Huangyan, China.

Discussing New York’s 9/11 Memorial forest, she shows how the design by PWP Landscape Architecture of Berkeley, California, uses pedestrian allées formed by 30 rows of swamp white oaks to direct visitors to the park’s two waterfalls within the footprints of the destroyed World Trade Center towers. In a sharp use of contrast as accent, the only other species of tree included is a single Bradford pear tree “that survived the attack and was nurtured off site for a decade before being replanted on the memorial plaza.”

Crandell is sensitive to effects created by designs that take advantage of staggered spring blossoming times or fall foliage changes. She smartly ponders how designs should be maintained as trees naturally die off. Should they be replaced? With the same species? One by one? Or groups at a time to maintain symmetry in size and shape? She asks a big question underlying the field: How can a living, changing landscape be maintained as historic? And should it?

Crandell’s singular focus on designs favoring straight lines, grids and other geometry is compelling, but too narrow. And it can lead her astray—as when she addresses Frederick Law Olmsted’s mid 19th century designs for New York’s Central Park.

Olmsted’s style came out of the tradition of English gardens, which rejected the geometric order of French gardens like Versailles in favor of elaborate artifice that aimed to make the gardens appear natural. The English style drew inspiration from overgrown Roman and Italian ruins, identifying this wildness as freedom.

Olmsted adapted it for democratic American purposes in Central Park and Boston’s Emerald Necklace parks. Trees in his designs serve as elements of focus, but also screen one area from another. So you can walk through the various landscapes of these parks relatively quickly, but the distinctly changing scenery, one section screened from the next, makes it seem a longer and more dramatic journey.

Addressing Central Park, a world-renowned landmark of designed wildness, Crandall focuses on its Mall, an allée that is practically the only section of the park featuring the sort of strict geometric order she favors. It’s the exception to the rest of the design that serves to accent the rest by its contrast. But Crandell addresses it as if it were the main event, which is just backwards.

“Like orchards and nurseries, planted forests inherently possess the geometry of the grid,” Crandell asserts late in the book. You only need visit Central Park or Boston’s Franklin Park to recognize the error of this sweeping statement.

What does Crandell leave out? The “rural cemetery” movement that combined the early United States’ need for larger burial grounds with its desire for more public parks to produce garden park cemeteries like Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, founded in 1831. She overlooks things like Danish-American landscape architect Jens Jensen’s 1916 to ’18 “prairie style” designs for Columbus Park in Chicago, with waterfalls and streams flowing through trees; Disneyland’s use of plantings to project mood and fantasy narrative at the California theme park, beginning in the 1950s; and new playground design like Amsterdam firm Carve’s 2010 Vondelpark Canopy Walk, which erected wire-mesh bridges that allow children to explore the tree tops of an Amsterdam park.

Crandell’s celebration of Modernist geometric landscape design also results in a more troubling blindspot. Industrial Modernism hasn’t been great for the environment. Yet even in the contemporary designs in the book, sustainable ecology is usually low on the architects’ apparent list of concerns, if it’s on the list at all. It's dismaying that this inattentiveness is pervasive at the top of the landscape design field even as environmental threats like global warming are ever more pressing.

This article was originally published on April 25, 2013.

This program aired on April 25, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.