Advertisement

Belcher’s Sensitive Portraits Of African-Americans In Jim Crow South

When Hilda Belcher visited Savannah, Georgia, to paint a portrait commission in 1913, the city captured her imagination. Though she continued to live in New York, Savannah repeatedly drew her back in the 1920s and ‘30s to paint prominent Southern citizens and African American life in churches and on front porches.

Sensitive depictions of black Americans by white Americans during that period are rare. So these paintings stand out in an exhibition of the late artist’s work at Martha Richardson Fine Art (38 Newbury St., Boston, through May 31).

Belcher (1881-1963) grew up around Pittsford, Vermont, where she was born, and Newark, New Jersey, where her family moved before 1900. She went to New York to study at the Art Students League, where she would go on to teach, and at William Merritt Chase’s Chase School.

Her teachers included social realists affiliated with the Ashcan School, a loose group of artists dedicated to the depiction of gritty, everyday American life. Her own work varied between tender family scenes, like her watercolor of a calico kitten or a 1916 portrait of a young niece, and portrayals of denizens of restaurants and diners on New York’s social scene. She earned money making cartoons and illustrations for “Harper’s” and “Woman’s Home Companion” magazine and designs for her father’s company, Ecclesiastical and Domestic Stained Glass Work. Her paintings often have the charm, the animation and the essentializing of cartooning or caricature.

The African American cultural effloresce of the Harlem Renaissance—Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, James Van Der Zee, Aaron Douglas, Archibald Motley Jr., Jacob Lawrence—helped draw the attention of some white artists to black American life.

In the 1920s and ‘30s, Thomas Hart Benton traveled in the Jim Crow South and painted sharecroppers, a minstrel show and men loading cotton onto a boat. Al Hirschfeld, now best known for his caricatures of Broadway performers, published a book of drawings of Harlem folks in 1941. These artists sought to consider racial oppression in America as well as the achievements of the jazz culture electrifying music. Though progressive for their eras, they still can fall into stereotypes of their times which sometimes read as bigoted now. Particularly because both Benton and Hirschfeld’s styles, like Belcher's, blended careful observation and caricature.

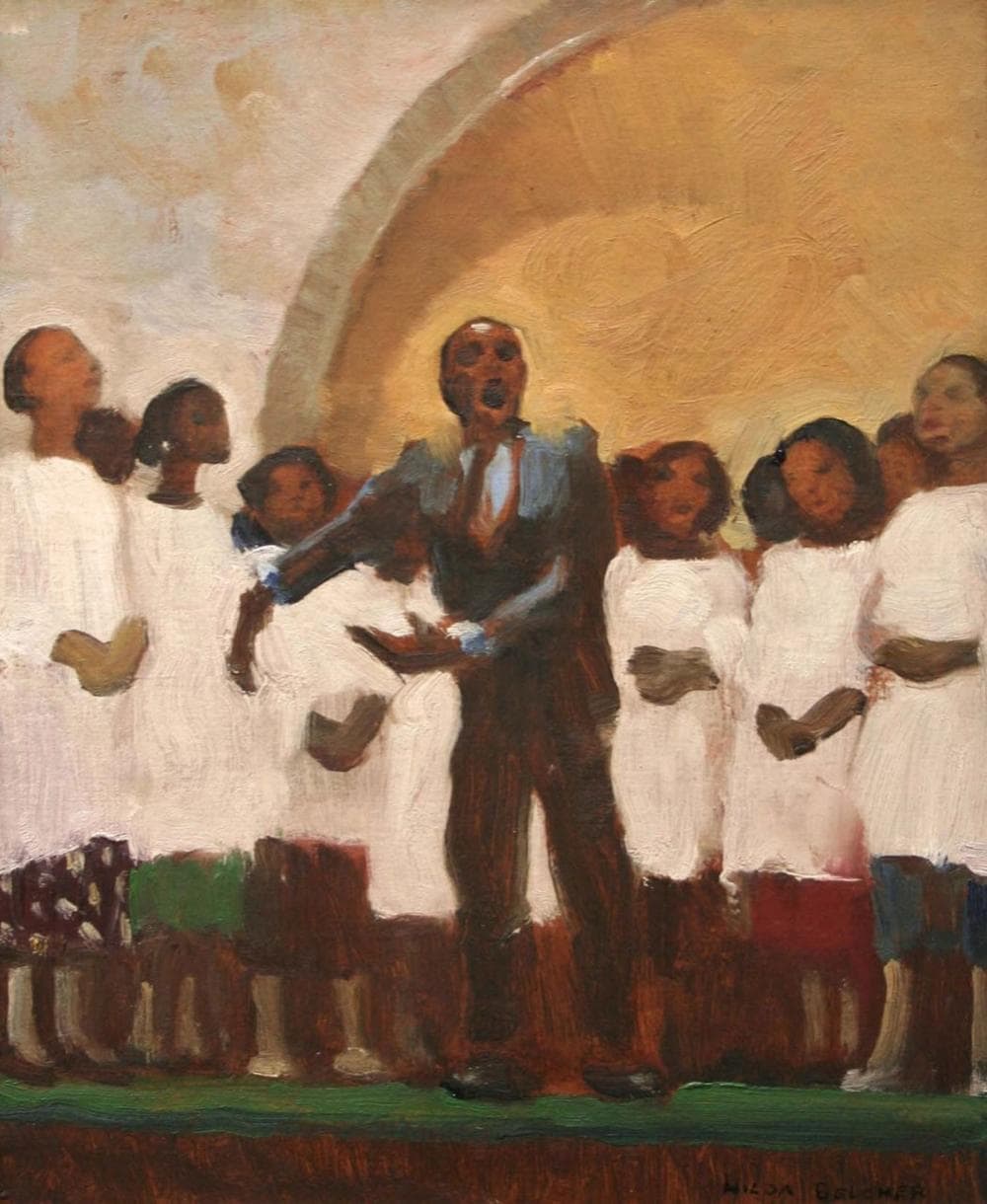

Belcher’s Savannah watercolors carefully depict children dressed in their Sunday best in church; a woman in blue hat and white pearl earrings and necklace; and a group gathered under a tall tree on a sunny Sunday morning. Her dynamic 1934 oil painting “The Choir" shows a black minister leading white robed choir ladies in song. It’s a loose, brushy study for her larger 1936 painting “Go Down Moses,” now in the collection of the Greenville County Museum of Art in South Carolina. But you might wonder if stereotype is seeping into her watercolor of women gathered on the porch of “the Old Negro Cabin.”

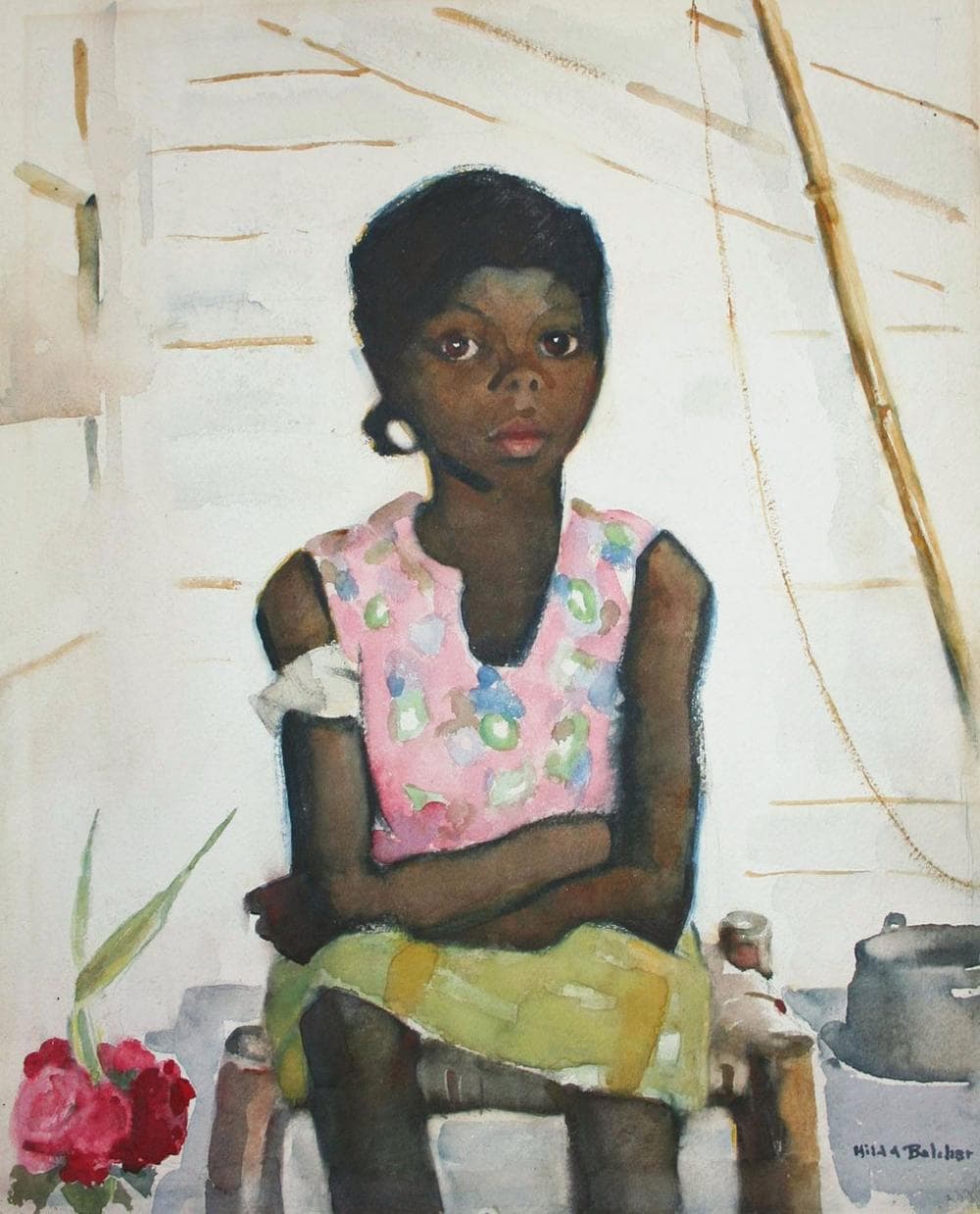

The best of Belcher’s Savannah work is a straightforward 1940 watercolor portrait of a young African-American girl, Arabella Martin, seated outdoors wearing a flowery top and plaid skirt. Her slender arms are folded across her belly and she stares with big brown eyes, thoughtful, but on guard.

This article was originally published on April 30, 2013.

This program aired on April 30, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.