Advertisement

The Drawing To End All Drawings: Joe Sacco’s 24-Foot Panorama ‘The Great War’

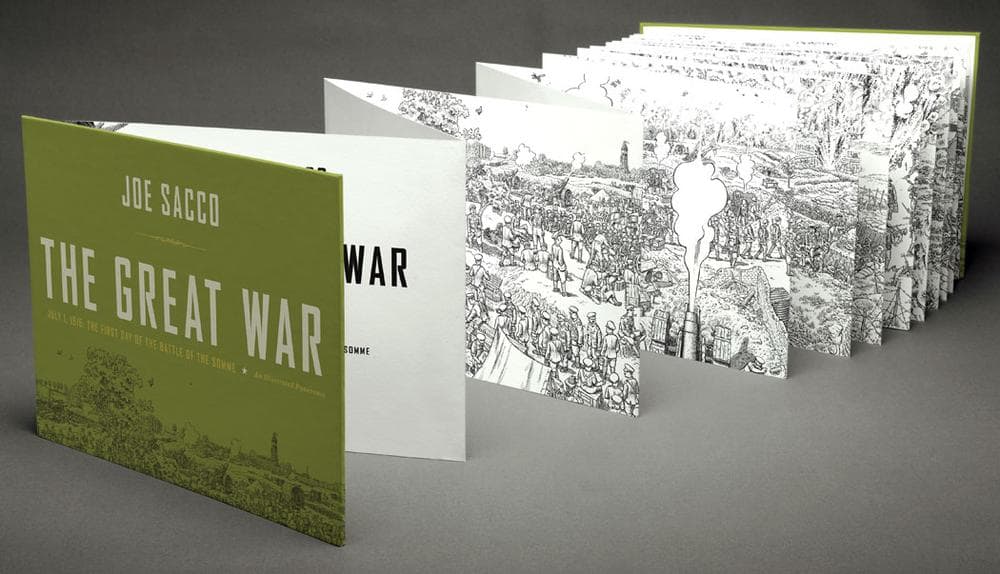

Veteran war journalist-cartoonist Joe Sacco’s latest project “The Great War” isn’t so much a book, as just one drawing—an “illustrated panorama” of “July, 1, 1916: The First Day of the Battle of the Somme.” But what an epic, bloody drawing. The paper unfolds to 24 feet long. It feels like miles.

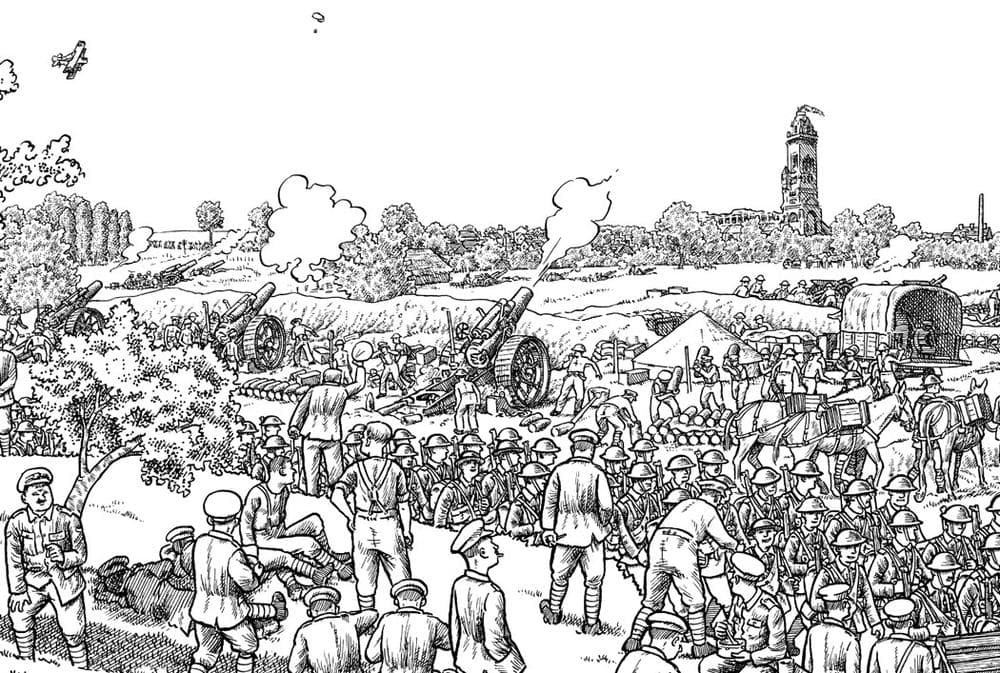

Sacco’s black-and-white depiction of one of the deadliest and most infamous battles of the First World War is overwhelming and wondrous, much vaster than you can take in at one glance. It moves from left to right, chronologically, but also travels from behind the lines to the front-line fighting, then back to the rear again. He focuses on thousands of British troops, beginning with a general strolling the grounds of a mansion. A convoy of horse-drawn supply wagons trots forward. Soldiers queue up for chow. Troops march to the front. Howitzers blast at the Germans. A maze of trenches overflows with infantry.

The British plan was to overwhelm German lines by concentrating some 500,000 troops on a small area of wheat and sugar-beet fields along the Somme River in northeastern France, near Belgium. The battle was preceded by a nearly- week-long artillery bombardment of 1.5 million shells and toxic chlorine gas.

Sacco, who lives in Portland, Oregon, is best known for his nonfiction graphic novels “Safe Area Gorazde: The War in Eastern Bosnia, 1992-95” and “Palestine.” When invited by his editor at W.W. Norton & Company to take on this project, Sacco writes in a 16-page accompanying booklet, “My first thought was, ‘I don’t want to draw another war scene.’” He adds, “I decided to depict the first day of the Battle of the Somme because that is the point where the common man could have no more illusions about the nature of modern warfare.”

Sacco's touchstone here was the Bayeux Tapestry, a 230-foot-long embroidered depiction of an 11th century Norman invasion of England that was perhaps completed a decade after the fighting. Sacco’s drawing is also in the 19th century tradition of 360-degree panorama paintings of battles, historical scenes and exotic travels that filed specially-constructed round buildings called cycloramas. For example, a 359-foot-long painting of Civil War fighting at Gettysburg, which was originally shown at the Boston Center for the Arts’ Cyclorama in 1884, is now displayed at Gettysburg.

At 7:30 a.m. on July 1, 1916, whistles blew to launch the British assault. Sacco depicts men climbing ladders and plodding into no-man’s-land, where they’re blasted by German artillery and machine-gunned. Some hide in shell craters. Bodies lay shattered in the dirt. Wounded are carried on stretchers toward overflowing aid stations and field hospitals.

The days of artillery bombardment were supposed to knock out German barbed wire and machine gun bunkers, but most remained intact. As British headed for the gaps, they bunched up, making concentrated targets for the German gunners.

Sacco’s drawing concludes with a chaplain watching men dig a cemetery. In the background, a long line of infantry apparently continues marching to the front.

The movement of the men toward their doom feels like an inexorable tide. The drawing powerfully puts you there, in one, long, incredible, uncut movie tracking shot. Or the view of a god watching carefully and closely, but without intervening. Time slows, but still proceeds boot-step by boot-step toward tragedy. Sacco conveys it with a funereal tone, suffused with a feeling of the battle’s folly, but the drawing itself is dazzling. All the violence somehow adds to the thrill.

The Germans suffered some 8,000 casualties while, Historian Adam Hochschild writes in the pamphlet’s introduction, “some 21,000 British soldiers [were] killed or fatally wounded on the day of greatest bloodshed in the history of their country’s military, before or since.”

Follow Greg Cook on Twitter @AestheticResear

This article was originally published on November 11, 2013.

This program aired on November 11, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.