Advertisement

In Apollinaire's 'Greenland,' Family Ties Melt Away

“Greenland” is an appropriately icy play for this exceptionally snowy Boston winter. Written by Canadian playwright Nicolas Billon, the play centers on the real discovery of an island that was originally thought to be part of Greenland’s mainland and was only recently revealed by a drifting glacier, a theme echoed by the rift of the central family.

Presented by Apollinaire Theatre Company at Chelsea Theatre Works, “Greenland” opened on Feb. 20 and plays through March 15. While climate change is behind the play's central conceit, director Meg Taintor emphasizes that "Greenland" is far from agitprop.

“In ‘Greenland,’ climate change is just a given,” she says. “It’s just a fact of reality for these characters, but it’s not the center point of the play.”

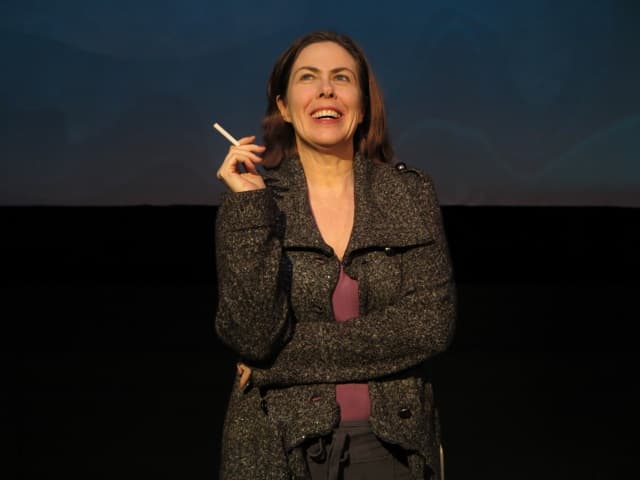

Instead, the focus is on the family of the glacial scientist who discovered the island. The play comes in at under an hour, and it consists of 17- to 19-minute monologues from the three members of the family: the scientist (portrayed by Dale J. Young), his wife (played by Christine Power, who will be replaced in the last week by Gillian Mackay-Smith) and their adopted daughter (Charlotte Kinder). The set consists of a single chair and an illuminated painting of a glacier. The glacier serves as metaphor for the family drifting apart, and the details of the familial rift are only gradually revealed over the course of the play.

“While [the characters are] being very straightforward and honest about some things, they’re also dancing around their central pain in very interesting ways,” says Taintor. “You very slowly piece together what the actual tragedy is.”

Islands drifting apart isn’t the only climate change metaphor in the story. Taintor recently spoke to a Northeastern class that’s studying the play. One student was able to convey the link between climate change and the characters in a way that strongly resonated with her.

“Climate change is a demonstration of us making bad behavior over and over again and not learning from our mistakes,” Taintor says, paraphrasing the student. “We know that it’s a catastrophic problem, but we refuse to stop guzzling oil and natural gasses. In the same way, the characters in this play know that they are critically damaging their relationship and their ability to connect with each other, and yet they aren’t able to stop doing it.”

It’s clear that Taintor cares deeply about the environment. She was raised by activist parents, and she’s been involved with Boston climate change groups. The timing of presenting a play with a backdrop of climate change in this particular winter is not lost on her. “We’re in a living example of why we should all be concerned about what’s happening to our environment,” she says. To emphasize the immediacy of the events on stage, performances on Feb. 27, and March 8 and 15 will feature a talk-back from MIT’s Dr. Carl Gladish who will discuss the glacial science in the play.

Taintor herself has recently drifted away from Whistler In The Dark, the theater company that she directed for nine years. While she remembers her time at Whistler fondly, she also doesn’t mind avoiding the logistical minutiae of running a theater company. Instead, she’s been able to focus on directing plays she loves and on challenging herself. There isn’t a particular type of play she’s been drawn to since her departure; the last two performances she directed were “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead” and “Henry IV,” about as far from the minimal modernism of “Greenland” as possible.

Taintor was originally drawn to Billon’s work after seeing a Halifax production of his play “Iceland.” “It was so sparse and spare and elegant,” she remembers. “So much of the experience of watching it was just realizing how much as a playwright Nicolas trusted his actors and directors to not get in the way of the play.” Both “Iceland” and “Greenland” are part of Billon’s “Fault Lines” trilogy, all short plays that center on island nations.

Billon sent Taintor the trilogy after she expressed her admiration. She fell in love with “Greenland,” immediately impressed by the emotional complexity and destructiveness of the characters, especially that of the wife, Judith. “Her first line is ‘f**k the polar bears.’ If any character introduces herself to me like that, I’m in. That’s ballsy.”

As Taintor watches Christine Power as Judith at a pre-show rehearsal in mid-February, she seems just as engaged with the character, laughing at her funny lines and nodding in appreciation of weightier moments. (“As a director I tend to perform audience for my actors” she says.) She remains aware of the danger of over-rehearsing, especially in a play as sparse as “Greenland.”

“All theater is that dancing act of trying to find spontaneity,” she says. “But in this play, because it’s so spare — there’s no crazy staging, they’re just sitting there or standing there — it’s really noticeable if anything isn’t exactly lived in the moment.”

Watching her react to Judith’s devastating monologue, there doesn’t seem to be any danger of that. The rehearsal has a relaxed energy, and Taintor is friendly and encouraging in her notes. Judith’s story is that of a wife in an unhappy marriage, smoking a cigarette to spite her husband. “The only time he tries to communicate is when he talks to me about ice,” Power says as Judith, and Taintor nods in solemn appreciation.

Though it might be thematically appropriate, Boston’s snow has been devastating for theaters (and commerce in general). But Taintor hopes that weather won’t deter people from venturing out to Chelsea to see “Greenland.”

“It’s short, it’s thought provoking and it’s really surprisingly moving. I think audiences will really respond to it,” she says. “The trick is getting audiences out the door right now.”