Advertisement

Rum, Rumba, Slaves And Ghosts: A New Art Installation Evokes The Cuban Sugar Industry

Resume

For more than a century Cuban sugar fueled the global rum industry. The refined cane made its way from the small island nation to bustling trading ports in U.S. cities like Salem, Massachusetts.

Now, a Boston-based, Cuban-born artist and her American musician husband are bringing the sights, sounds, smells and ghosts of Cuba’s now abandoned sugar fields and factories to the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem through a multi-sensory installation.

From the get go, the new work — called "Alchemy of the Soul" -- transports visitors to a version of Cuba that’s very different than what you see on postcards and in travel guides. There are no jerry-rigged American cars or images of Che Guevara.

Instead, this journey starts with a ride up to a second floor gallery in the museum’s utilitarian freight elevator. Burlap sacks of sugar flank a record player spinning a 45 of a traditional Cuban music.

“We wanted to use the freight elevator as like a dock,” jazz musician and composer Neil Leonard explained, adding, “and Cuban rumba came from the docks.”

This professor at Berklee College of Music has traveled to Cuba many times over the decades.

“The most famous rumba group to come from the docks featured [Raphael] El Niño Pujado, so we asked him if he would record some songs that he sang — on the docks, carrying sugar, as a young boy,” Leonard recalled.

Leonard’s sparky, articulate wife María Magdalena Campos-Pons chimed in to elaborate on the dock workers and history evoked by the rumba musician's singing.

“These were the people who were trading the sugar sacks that were exported out to Massachusetts, where the rum — the liquor — was going to be processed and made,” Campos-Pons told me.

This Afro-Cuban visual artist and performer — known by her husband and close associates as Magda — is a descendant of Yoruba slaves who toiled in the brutal sugar industry. Leonard, on the other hand, grew up outside Philadelphia. They were both born in 1959, the same year Fidel Castro took control of Cuba, a move that inflamed relations between the tiny country’s leader and former U.S. President John F. Kennedy.

“Magda's a daughter from Castro’s country,” Leonard mused, “and I’m the son of a Kennedy's country.”

“I married the enemy,” Campos-Pons followed up, laughing, “and when we married, that was not fashionable. Neil had gone to Cuba many a number of times with Berklee College of Music when not many people were going. He went to Cuba before he met me. So this was destiny.”

The couple's shared passion for Cuba drove them to create a collaboration that is poignant and personal. Leonard says they traveled to Matanzas — located on Cuba's north shore — and inland so they could gather music, interviews, sounds and research on the country's sugar trade specifically for the museum's commission.

“We went to sugar factories, we talked to people who worked in sugar factories, and we thought about what came from Matanzas to Salem,” Leonard said of their trip, “and one thing would be sugar — but another thing that came through a slightly different route was music.”

From the elevator we walked into an open, spacious gallery. The sights, smells and Leonard’s ephemeral, sometimes eerie, soundscape fill the room. Campos-Pons encourages me to sniff the air for a sweet, liquor aroma.

“When you arrive here and you hear the sound of the distilling of the rum — you even sense the kind of humidity — that captured the sort of experience that I remember when I was younger,” she explained, then remembered, “I used to say before I come back to La Vega that the smell of burning sugar and processing sugar stay in your nose, enter your brain, and never left you.”

As a child in Cuba, Campos-Pons’ tight-knit family lived in former slave barracks in the sugar hub La Vega. She’s returned to the Matanzas area many times over the decades, but before this installation she hadn’t been back to La Vega in 30 years.

In the gallery, the artist has created the landscape of her youth with six, large-scale, glass-blown sculptures. They’re like transparent, industrial silhouettes — towers, silos, smokestacks — that summon memories of sugar refineries and the distilling process. Campos-Pons tapped skilled glass studios in San Francisco and Boston to make them. She said hundreds of now defunct, decaying sugar operations remain scattered throughout Cuba’s countryside.

“For me it’s the commentary about the ruins, the commentary about the ghosts,” the artist told me.

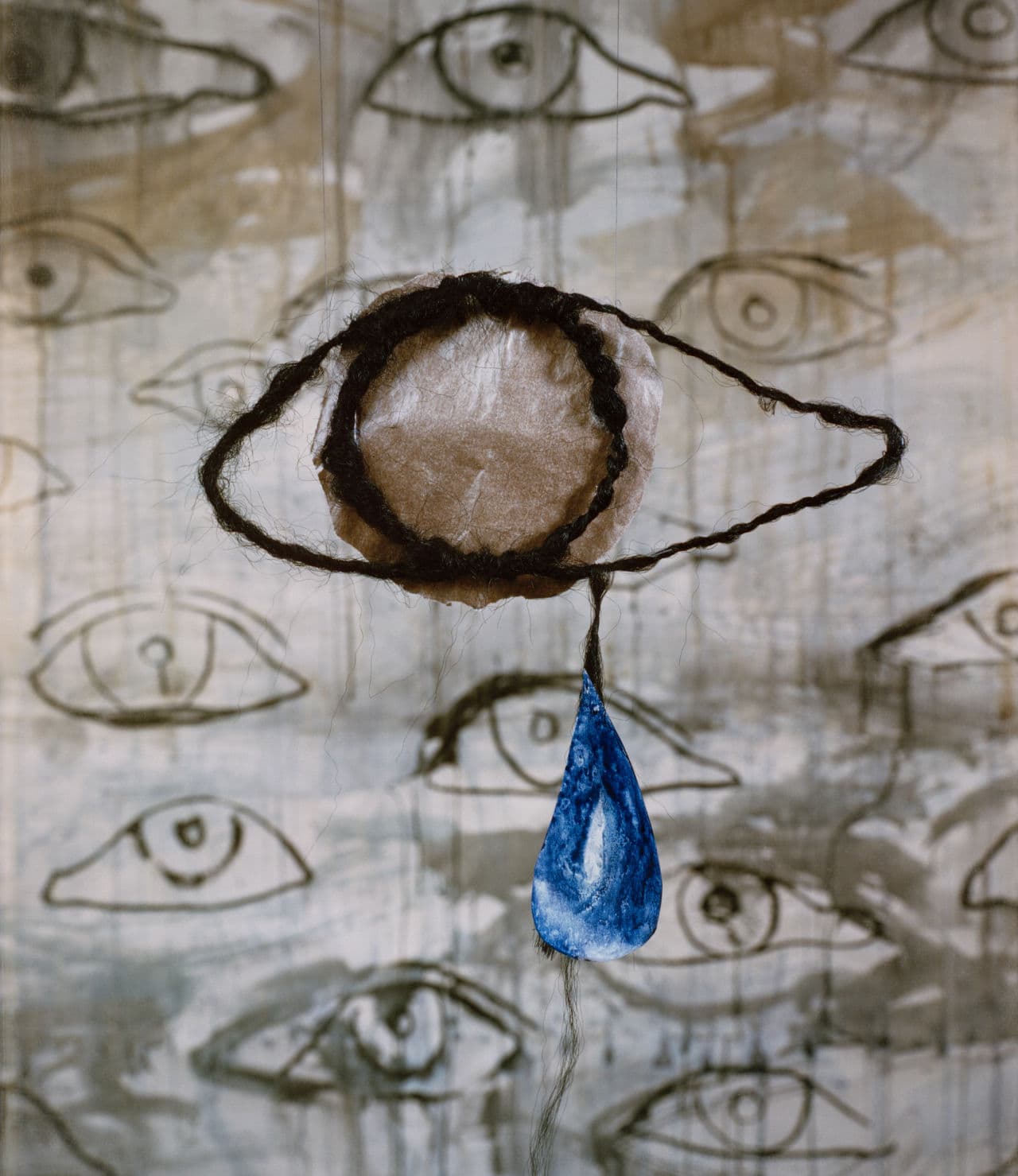

Campos-Pons says the ghosts of her slave ancestors are in the gallery, too. With this autobiographical display the artist is conjuring the tension between rum — or “liquid gold” as she calls it — and the barbaric working conditions the slaves in the fields and refineries were forced to endure.

“The use of the black bodies and the slaves — and the labor that was always unrecognized for what it was — there was always element of exploitation and abuse to some extent,” Campos-Pons said, “but out of that comes this glorious, gold, wonderful liquid. Like alchemy.”

In La Vega, Campos-Pons says she could feel the ghosts of female slaves, and marvels at their strength.

“From where they found the energy after 12 hours in the field to come home and to breast-feed an infant after breast-feeding the infant of the master? Was any left for a woman to give milk to her own offspring?” the artist asked, looking right into my eyes. She even created a performance piece inspired by that particular image: “This is the story of this piece.”

Peabody Essex Museum deputy director Josh Basseches sees many narratives in the new installation. He actually stepped out of his usual role to curate this collaboration.

“One of the things that I find so powerful about Magda’s work is that under-girding it all are important issues about loss and exile, and family connections, and labor, and the history and impact of slavery,” he said. “But she does not push these issues down your throat. She is suggesting them with art that is beautiful and aesthetically lyrical.”

Basseches added that the international contemporary artist is grabbing a lot of respect and attention these days. This past December Campos-Pons was named one of the top 100 global thinkers of 2015 by Foreign Policy magazine.

Basseches also said the provocative artist and her frequent collaborator-husband musician (who also is artistic director of Berklee Interdisciplinary Arts Institute) have been deeply engaging in cutting-edge artistic conversations about Cuba-U.S. relations since they married in 1989. With "Alchemy of the Soul," Campos-Pons and Leonard are bringing their creative dialogue to the public.

“Art is only an artifice. When we are here [in the installation] we could say to you, ‘Welcome to Cuba,' " Campos-Pons said, "but it’s an artifice of Cuba." She and Leonard want visitors to walk away from the installation asking real questions and pondering real issues.

“What is Cuba? The role of sugar? The role of rum? The role of art? Our relation to it? Our relation to Cuba?” she listed off. If that happens, she added, then the couple will feel successful and proud.

Campos-Pons sees every piece in her body of work — including "Alchemy of the Soul" — as prayers for the future and says she and her husband are feeling optimistic.