Advertisement

How Plastic Flamingos Fit Into The Fitchburg Art Museum's Mission To Serve Its Struggling City

Resume

The Fitchburg Art Museum (FAM) in central Massachusetts is on a mission to redefine its role.

"Many art museums are very busy serving art — and we look at it a little differently," director Nick Capasso explained. "We are here to serve people."

A new exhibition reveals how he and his museum team are using contemporary art, industry and plastic pink flamingos to connect with the community.

Art's Place In A Gateway City

Over the last three years Capasso has been working with leadership, curators and educators to devise ways they can make a difference in a city that’s struggling.

"Fitchburg is a Gateway City — the euphemism for old, dying mill towns — and it’s got a lot of problems,” Capasso told me on a recent visit. “But one of the great strengths of this city is its art museum. And we need to do everything we can do to help the community in any way it makes sense for a museum to do that.”

It made sense, for example, to make the gallery's labels bilingual because one-fourth of Fitchburg’s population is Latino and many residents speak Spanish at home. But the FAM director says he and curators including Mary Tinti also wanted to create exhibitions that would engage with the community and surrounding region in a real, accessible way — which can be challenging with contemporary art.

The answer? A series of shows that connects to the area’s long industrial legacy of producing furniture, paper and plastics.

“Because Leominster, our sister city, was the plastics capital of the universe for a long time,” Capasso said.

Think Tupperware and the popular mid-20th century plastic container’s “burping” seal. Foster Grant sunglasses — made famous in TV commercials starring Sophia Loren — were also made in Leominster.

Then there’s the flock of pink flamingos striding across the museum’s front courtyard. Some people assume the iconic plastic lawn ornament hails from the South, but it’s actually homegrown in Massachusetts.

“It’s a sculpture,” Capasso continues. “It was created by an artist, Don Featherstone. He created that flamingo in 1957 by carving a mold out of steel.”

Linking To An Industrial Legacy

In the FAM’s gallery, curator Lisa Crossman points to a picture of Featherstone. He’s included in a timeline of plastics pioneers who fueled a manufacturing boom in the area.

“There are a lot of great pictures of him,” she said. “He and his wife actually wore matching outfits.”

Earl Tupper’s image is up on the wall, too.

Crossman says the new exhibition, “Plastic Imagination,” links their pasts with 10 present day New England artists who use the ubiquitous, versatile material as their medium.

“It’s part of 20th and 21st century art,” Crossman says, “and it’s part of so many things that we wear, hold, use, make — all these things. So I think the show really captures that, along with some of the playfulness of plastics and the possibility that it provides — but also some of the darker implications.”

A number of the artists seem to have something of a love-hate relationship with plastic. Crossman calls the material a "conservator’s nightmare" because while it doesn’t biodegrade readily, it’s actually difficult to preserve artworks made of plastic.

This kind of tension fills the exhibition. There are pieces made of Plexiglas, foam, zip ties, polyurethane.

“It’s super easy to carve, and it’s stable,” Boston artist Bill Thompson explained holding a dense, polyurethane block in his hands.

“It’s used by a lot of industrial designers for model-making and prototyping,” he said, “so it’s absolutely perfect for what I do.”

Thompson creates organic-looking figures from man-made material. After he coats them with car paint they look like slick, colorful amoebas or slugs on the gallery’s walls.

“The organic forms that I carve — and the fact that I’m making them out of these decidedly unnatural materials, implies that tension,” he said. “It’s submerged in the pieces and not totally obvious.”

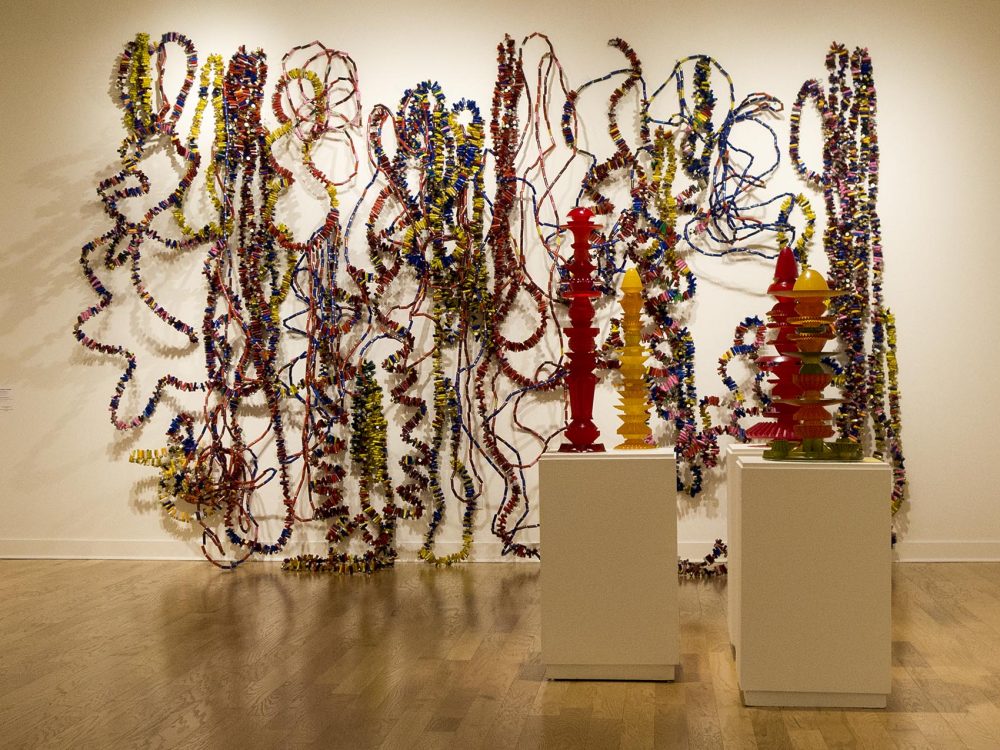

From a distance, artist Margaret Roleke’s red, yellow, pink and blue wall sculpture titled, “Shell Symphony,” hangs in pretty loops and curls, kind of like garlands for a Christmas tree.

“But when you get closer — and see it’s a bunch of shot gun shells — you begin to think beyond it,” Crossman mused.

As you walk toward either of the two pieces by Tom Deininger they almost look like 3-D impressionist paintings. Then your eyes focus in on individual forms in a mass of plastic. There are action figures, credit cards, bottle caps, spoons.

“I find these kind of overwhelming,” Crossman admitted, “really eye-catching but also anxiety-provoking.”

That’s the goal for a lot of the artists, including Lisa Barthelson. She transforms piles of plastic packaging and discarded toys her family accumulates into pieces for a series she calls, “Family Debris.” Barthelson describes her work as a form of “penance.” She created six new works for the “Plastics Imagination” show.

“It makes so much possible — but in fact it’s with us forever,” Barthelson said reflecting on the material. “I like to get people interested seeing the color, the shape, the beauty of the plastic items. And then I want them to think about where it came from, where it’s going, why do we need it all.”

Barthelson lives in Rutland — not too far from Fitchburg. She’s known about the history of plastics in central Massachusetts for a while, and even has a few pink flamingos of her own.

But for Boston plastics artist Niho Kozuru, participating in this show has been illuminating. She thinks a lot of other people will feel the same way.

“I had no idea that this industry existed,” Kozuru told me, “so for us to have a chance to learn about it and to acknowledge the past, I think, is very important.”

'We Are Still Here'

It’s not just the past, FAM director Nick Capasso explained. “They’re still here,” he said.

There are about 70 plastics companies in central Massachusetts.

“Well, yeah — we are still here,” Claude Chapdelaine, vice president of Cado Company in Fitchburg, confirmed with a laugh.

His company purchased Don Featherstone’s Union Products and now fabricates 50,000 to 60,000 pink flamingos a year.

Chapdelaine took me on a tour of his facility and showed me how air is injected into the original Don Featherstone mold that’s filled with molten, Pepto Bismol-colored plastic.

“It sets for about a minute and a half to cool down, then it comes and is trimmed by two people over here,” he explained.

Depending on the season Chapdelaine said Cado employs between 30 and 50 people. The company also makes other plastic lawn ornaments including garden gnomes and snowmen.

“We also manufacture products that are owned by other people that don’t have manufacturing facilities,” he continued. “As far as our product line — all this lawn and garden stuff — it has not been able to morph overseas primarily because it’s big and bulky and freight costs are very high. So we have been able to keep these types of products in this country and we’ve been very fortunate for that.”

Chapdelaine, now 72-years-old, grew up in Leominster and has worked in the industry since he was 13. He’s happy the Fitchburg Art Museum is highlighting plastics’ role in the area.

“It’s important that the people of the region realize what this has done for the economy over the years," he said. "There are a lot of new people moving into these areas and they're not familiar with the history of the plastic and hopefully a lot of people will see that and understand where the plastic industry comes from and how it’s grown.”

It might not be what it once was, but Chapdelaine says the plastics industry has employed thousands over the years and continues to boost the region’s economy. The idea that an exhibition is celebrating the art and legacy of plastics doesn’t surprise him. After all, he adds, the plastic flamingo is in the collection at a Smithsonian museum.

This segment aired on October 13, 2016.