Advertisement

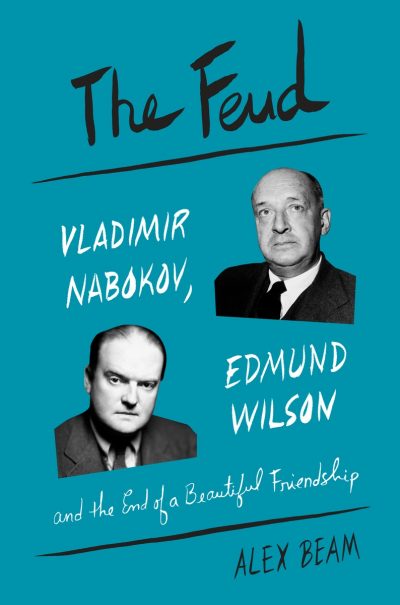

Alex Beam Makes 'The Feud's' Literary Squabble More Fun Than It Has Any Right To Be

A literary feud is like a gunfight with words. If that doesn’t sound like a particularly thrilling topic for a book, consider this: Typically the combatants are all too full of themselves, and mixed amid the invective and righteous indignation, are some excellent zingers.

In the end, no matter how great the writers involved are — to paraphrase Shakespeare — buffoonery will out. Or, as Alex Beam puts it in his entertaining new book, "The Feud," it can all be a bit "silly."

That’s the word the Newton-based author and Boston Globe columnist uses to describe the postwar battle between two literary hotheads at the heart of his new book.

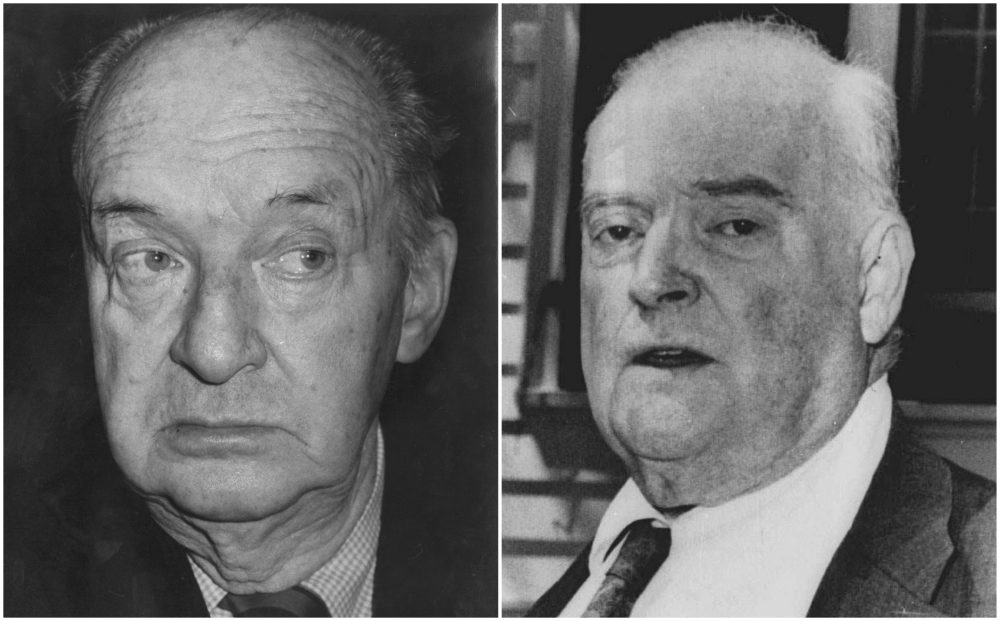

In this corner we have Vladimir Nabokov, the Russian-born author of "Lolita" and many other novels, as well as a great autobiography, "Speak, Memory." In the other, we have the one-time dean of American critics Edmund "Bunny" Wilson, who is more likely these days to be confused (even in learned company) with Edward O. Wilson, who is very much alive and writes books about ants.

The Nabokov-Wilson battle was over a Russian novel, "Eugene Onegin," known in the western world as an opera by Tchaikovsky, but for generations of readers back in the motherland, Alexander Pushkin’s 389 stanzas comprised the "unrivaled masterpiece of their literary canon," as Beam puts it. The fact that the text defies straightforward translation is the heart of the matter, and proves to be the final straw of the two writers' friendship.

The beginning of that friendship dates to 1940. Wilson was the closest littérateur to Samuel Johnson that mid-century America had produced, and Nabokov was marooned in Russia, broke and looking to make a soft landing in the U.S. Wilson provided the entrée, connecting him with editors and publishers, and the two men became fast friends. A Nabokov biographer said the Russian author’s letters to Wilson were the “most protracted and voluminous” in his archives. Both men hated academia (but took its money), loved to discuss anything involving Russia (Wilson had spent several months there in the early 1930s), enjoyed playing the part of an esteemed man of letters, and, on at least one occasion, borrowed socks from each other.

Over the years, there were cracks in the relationship — especially after Nabokov hit the literary jackpot with his 1955 novel “Lolita” and Wilson’s health and fortunes began a long downward trajectory. However, it wasn't until Wilson wrote a scathing piece in The New York Review of Books about Nabokov's comically overlong and "unreadable" (according to Beam) translation of "Eugene Onegin" in 1965 that their friendship took a turn for the worse.

Nabokov’s translation ran to four volumes and more than 2,000 pages. He unabashedly trashes the work of earlier translators, all the while making odd word choices in his own epic translation and going on page after page after page about such things as whether "pochuya" indicates that a horse "sniffs" or "smells."

Beam lets Nabokov bluster forth and, in time, become his primary straw man, and we readers get to witness him (and many critics of the day) take the great novelist and self-proclaimed “genius” down a few pegs.

As for Wilson, in his review of his friend’s "Onegin" translation, he wrote of its "flat writing, outlandish words and awkward phrases," as well as its legions of inaccuracies. Beam contends in a hilarious summation that Wilson’s denouncement reflected poorly not just on Nabokov’s work but on him: The review “remains a classic of its genre, the genre being overlong, spiteful, stochastically accurate, generally useless but unfailingly amusing hatchet job, the yawning, massive load of boiling pitch that inevitably ends up scalding the grinning fiend pouring the hot oil over the battlement as much as it harms the intended victim.”

Touché!

As you may have concluded after reading Beam’s damnation, that it’s his attitude toward the dust-up and the two men in the ring that makes "The Feud" more fun than it has any right to be. After giving us bits of biographical detail about Nabokov and Wilson, a survey of their most important books, a mini-history of American letters of the 1940s, '50s and '60s, and a solid primer on why “Eugene Onegin” is such a masterful work (in the original Russian, that is), Beam lets the two windbags at center stage amuse us throughout.

Beam presages the final fallout, detailing the various flare-ups between the two men that had begun years earlier. After the break, he dissects the feud, finding both men at fault. Throughout, the author is not only an amiable guide, but also proves adept concerning Russian history and literature, and Pushkin’s famous novel. (Beam was the Globe’s Moscow correspondent earlier in his career.)

Reading “The Feud,” we may laugh at these famous writers and their prideful foibles, but it also forces us to think how far we’ve come and how much things have changed. Today, the idea of a public squabble over a 19th century Russian text is sort of quaint. But at any point in history, Beam shows us, how quickly such contretemps can turn silly.