Advertisement

Locally-Made Documentary Connects Pivotal Moment In Civil Rights Movement To Today

Resume

The St. Augustine movement has been described as the bloodiest campaign of the civil rights movement. It took place in Florida, at the site of the oldest European settlement in North America.

A locally-made documentary film, screening at the Boston Public Library on Thursday, depicts what happened in St. Augustine and how it became a catalyst for passage of the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964.

"I just recall being in the narrow streets of St. Augustine and having Klansmen, even children, attack us with rebel flags as we marched," Mimi Jones, a longtime activist in Boston, says in the documentary.

Back then she was just a 16-year-old high schooler from Albany, Georgia. She was part of a group of students who'd traveled south to protest segregation in St. Augustine.

The students staged wade-ins as they attempted to integrate the beaches of St. Augustine. And on June 18, 1964, Jones was one of the students who moved to integrate a swimming pool at the Monson Motor Lodge. They were in the pool when the motel manager began to pour hydrochloric acid into the water.

"It is as fresh in my mind as the morning dew, because when the acid was poured in the pool, the water began to bubble up," Jones recalls.

"It all happened so quickly," she says. "So after I started to scream, then I see this fully-clothed policeman jumping into the pool, over our heads."

But the officer wasn't jumping in to rescue them. He was there to arrest them.

"There were policemen waiting as we got out of the pool to take us off — bathing suit and all," Jones says.

Photos of the St. Augustine incident circulated around the nation — including one photograph that would become iconic. It shows Jones in the water — mouth open in fear — with the motel manager behind her emptying a bottle of acid into the pool.

As this was happening, a filibuster was underway in Washington over landmark civil rights legislation. The very next day the filibuster was broken and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 cleared the Senate.

"I'm often asked, 'How could you have so much courage?' Courage for me is 'not the absence of fear,' but what you do in the face of fear," Jones says.

Among the others who joined the St. Augustine movement was Mary Parkman Peabody, whose son, Endicott Peabody, was the sitting governor of Massachusetts at the time. At 72-years-old, Mary Parkman Peabody was arrested when she and a group of blacks and whites went to a fancy, segregated hotel restaurant in St. Augustine and sat down together. She spent two nights in jail.

The documentary shows the moment of her release when she delivers a message to the people of St. Augustine.

"Don't lose heart now because you're the ones on whom this movement rests. People will come and go because they live somewhere else, but you live here and you make this thing happen," she said that day.

The St. Augustine movement would become known as one of the most critically important campaigns in civil rights history.

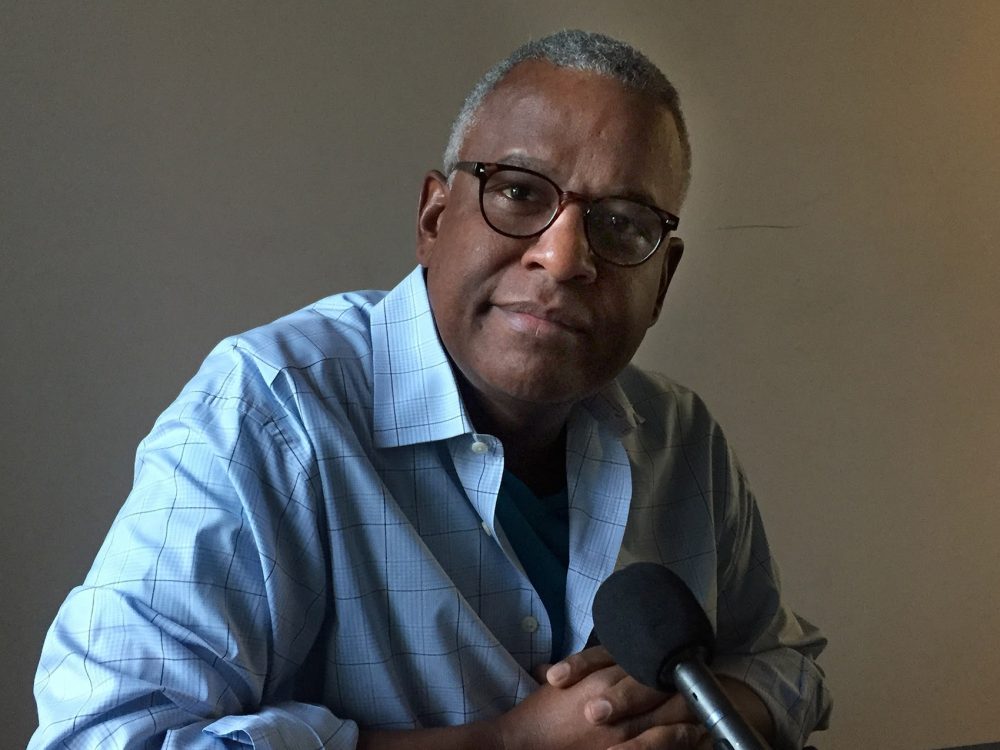

Filmmaker Clennon King, whose father played a key role as an attorney for the civil rights movement, produced the documentary. It's called "Passage at St. Augustine: The Story of a 1964 Black Lives Matter Movement That Transformed America."

As the title suggests, King sees a connection between the St. Augustine movement and the Black Lives Matter movement today.

"These kids understand that there is a connection between the Black Lives Matter movement, the civil rights movement and that movement that happened some 200 plus years ago down at Boston Harbor, where them bad boys got upset with the British because they were being taxed and not represented," he says. "It is the same fight that started a nation, it's no different."

King spoke a recent screening at the Grove Hall Branch of the Boston Public Library in Dorchester.

Among those in the audience was retired Lesley University professor Dolores Alleyne Goode.

"The film is important for its historical content, but it's also important for development of young people, recognizing that the same thing is going on in 2017 and they need to be prepared for their part in activism," Goode said.

The timeliness of the documentary also struck Roxbury resident Deta Galloway-Pitts, a registered nurse and a multimedia artist.

"Even though we have made tremendous strides in race, culture and class, many of the structural issues of racism, structural racism, division and even segregation continues — that it may bear a different face, but the particular kind of experiences that these communities experienced then in many ways are continuing," Galloway-Pitts says.

Galloway-Pitts feels the St. Augustine movement led to a transformation in the lives of black Americans. But she still sees the legacy of segregation — and the need for change.

"Not just a change about the smaller benefits, like we can walk down the street, but for the deeper changes in the political, educational and in the various communities that we have. We need real change," she says.

Galloway-Pitts feels that part of realizing that deeper societal change means educating, documenting and remembering.

This segment aired on February 8, 2017.