Advertisement

Here Are The 13 Artworks Stolen The Night Of The Gardner Museum Heist

On the morning of March 18, 1990, two thieves dressed as policemen walked into the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston and walked out with 13 pieces of art valued at half a billion dollars. Twenty-eight years later, it remains the largest unsolved art heist.

In September, WBUR and the Boston Globe are launching a podcast, titled Last Seen, that will dive into the heist's mysteries. (You could listen to the trailer and subscribe to be notified as soon as there are new episodes here.)

Before that, we asked critic Lloyd Schwartz to take a look at the art our city lost:

'The Concert'

Johannes Vermeer

1663-1666

This small painting, slightly more than two-feet square, was displayed back-to-back with Govaert Flinck’s “Landscape with Obelisk” on a small tabletop in the Gardner Museum’s magnificent Dutch Room. The Vermeer is generally considered the rarest and most valuable of the lost treasures — at least partly because so few of his paintings are known to exist. (The current consensus is 37, but some scholars still have doubts about the genuineness of three of them.)

“The Concert” is characteristic of the artist and also a little uncharacteristic. At least nine other Vermeers include musical instruments, mostly in the hands of women. Yet only three other surviving Vermeers include three figures (one is “Christ in the House of Martha and Mary,” the other two are set in a bar and in a brothel).

Silence is such a central quality of Vermeer’s work that even when he depicts a trio of music-makers (a singer accompanied by lute and harpsichord), the atmosphere of the painting is one of extreme quietude. The air of calm in this scene in an urban echo of the peaceful pastoral scene on the inside of the harpsichord lid (probably painted by Jan Wildens) and somewhere between the absolute silence of the woodland landscape and the raucousness of a transaction in a bordello in the two paintings hanging on the wall behind this wealthy and presumably respectable threesome. (The bordello painting, Dirck van Baburen’s “The Procuress,” which also has three figures, belongs to Boston's Museum of Fine Arts. In Vermeer’s time it seems to have been owned by his rich mother-in-law.)

Advertisement

Reinforcing this sense of calm, even among music-makers, is the painting’s complex geometry. The right and acute angles in the placement of the figures and the furniture, also the rectangular paintings on the wall, along with the refined, muted colors of the clothes (yellow, gray, brown) and jewelry (pearl earrings and a pearl necklace — also classic Vermeer) exude a hushed stability. At the same time, the softer curves of heads and bodies and clothes plus the aerodynamic sweep of the lid of the harpsichord add tension and energy to the static figures. The square marble floor tiles, radically foreshortened into diamond-shaped lozenges, not only greet but seem to actively pull the viewer’s eye into the scene. Just as the rectangular frames on the wall contrast with the more organic rhythms of the paintings they surround. And most Vermeer-like of all, an uncanny opalescent light both spotlights the figures and surrounds them with a mysterious stillness.

'A Lady And Gentleman In Black'

Rembrandt van Rijn

1633

All of the Rembrandts in Mrs. Gardner’s collection were produced by the early 1630s, when Rembrandt was only 26 or 27 years old (though his sensitive self-portrait — which wasn’t stolen — dates from four years earlier). He had already achieved a dazzling technical skill. Later images might be more profound, more searching, but these earlier masterful works were what made him famous.

Rembrandt painted many couples, some in very large formats. But the vast majority of these portraits are actually "pendants" — two separate canvases each picturing one member of the usually married couple. “A Lady And Gentleman In Black” is probably Rembrandt’s first double portrait including both figures on the same canvas. It’s impressively large — over 4-feet high by some 3½-feet wide. The colors are austere, but the clothing is rich, with amazingly detailed lacework (a Rembrandt specialty in this stage of his career), especially the woman’s elegant ruffled collar and lace cuffs. How tiny his brush must have been.

But what’s most striking about the painting is the position of the two figures. On the right, the woman is sitting in an elegant chair, looking out, but not at us — modest but self-possessed. Her left, gloved hand holds the glove of her naked right hand, which is resting on the arm of her chair. In the center, the man is standing, towering over her, swaggering, confrontational — his gloved left hand holding his right-hand glove; his right hand hidden, presumably on his hip, under his black cape. To his left is another chair, empty, simpler than the one the lady is sitting on. The seated woman, the standing man, and the empty chair form a triangle — the shape of solidity and stability. The room they’re in is quite spare, something — perhaps a map — is hanging on a wall behind the man. Also behind him are two steps leading up to a doorway his figure is blocking. Because we can’t really see the doorway, it seems more like an exit than an entrance. Though there’s an underlying tension, the situation is not about to change. The woman is strong, but not passive. The man is certainly in control — or thinks he is.

'Christ In The Storm On The Sea Of Galilee'

Rembrandt van Rijn

1633

Four artworks to the right of the stolen "Lady And Gentleman In Black" in the Dutch Room hangs the empty frame of the most famous of the missing paintings, “Christ In The Storm On The Sea Of Galilee,” an illustration of an even more famous passage in the New Testament (Matthew, 8):

23 And when he was entered into a ship, his disciples followed him.

24 And, behold, there arose a great tempest in the sea, insomuch that the ship was covered with the waves: but he was asleep.

25 And his disciples came to him, and awoke him, saying, Lord, save us: we perish.

26 And he saith unto them, Why are ye fearful, O ye of little faith? Then he arose, and rebuked the winds and the sea; and there was a great calm.

Rembrandt’s painting, from 1633, the same year as the portrait of the couple, is that painting’s almost diametrical opposite. Instead of calm stability, this is one of Rembrandt’s most dramatic and dynamic images. The canvas is just over 5 feet high and more than 4 feet wide — the effect is overwhelming. We are at the height of a violent storm. Dark clouds glower above, high waves are lashing the boat, the wind has already torn the mainsail in half. We almost can’t tell the waves from the rocks against which the small vessel seems about to founder.

Jesus and his disciples are in the boat. Some of them are in a state of panic. Some of them are working to hold the boat together. One is leaning over the side of the boat, about to vomit. One of them is staring out directly at us, holding onto his cap with one hand and onto a rope with the other. I’m not sure which disciple this is, but it’s Rembrandt’s face — the same face as in the also stolen “Self-Portrait,” a postage-stamp-size etching from the same period. With careful observation we can make out, in the midst of all this tumult, Jesus himself waking up from his nap and not the least bit worried. “Oh, ye of little faith.”

As opposed to the portrait of the couple, where every detail has been created by tiny, almost invisible brushstrokes, the brushstrokes here are wild, broad, windswept splashes across the canvas. We can actually see — almost touch — the vigorous brushing. It takes work to make out the small human faces. The boat has been swept up to an almost 45-degree angle to the water. As we watch, we ourselves are thrown off balance. (Or, rather, were.)

'Portrait Of The Artist As A Young Man'

Rembrandt van Rijn

1633

This tiny etching, just 1 inch and ¾ wide by nearly 2 inches high, is one of those Rembrandt marvels. We know from his other self-portraits and portraits of him by his students and other artists, that this is just what he must have looked like. Not yet 30, he’s already a successful, even famous artist, but he does nothing to flatter himself. He’s a little pudgy, a little scraggly, his hair is tousled and unkempt, and he looks very serious. In a bill of sale, this etching is referred to as “Rembrandt with three mustaches,” since he has a mustache on his lip, some hair on his chin, and even the brim of his cap seems to have a mustache.

'Landscape With Obelisk'

Govaert Flinck

1638

For many years, this haunting little landscape was thought to be by Rembrandt. Oil painted on wood, it measures 21 inches high by 28 inches across, and for all of its time in the Gardner Museum it was placed back to back with Vermeer’s “The Concert” over a small table near a window in the Dutch Room. The major oddity in this painting is the obelisk that gives this painting its title. On this dark and stormy day, it is streaked by sunlight, almost gilded, yet in perspective, it’s much smaller than the huge humanoid gnarled tree in the foreground, its windswept leaves like wild hair. A large section of trunk has fallen to the ground—struck by lightning? A miniature man on horseback is talking to another tiny man standing on the road (or is it a road?). Across the bridge (is there someone on it?), on the other side of a river, there’s a water mill. Against the distant horizon, a kind of butte towers over the fields and woods in front of it. The colors are mostly browns (the landscape) and grays (the sky). Bernard Berenson, the famous art historian and adviser to Mrs. Gardner, called it “a work of art of exquisite, sweet pathos and profound feeling.”

Fanciful and realistic, the subject remains a mystery. The obelisk seems to represent something, to want to represent something. It must be a symbol, or else what’s it doing there in the middle of this mostly barren landscape, in the center of this mysterious painting? But we have no choice but to leave its meaning to our imagination.

'Chez Tortoni'

Édouard Manet

Around 1875

A dapper mustachioed young man wearing a top hat is sitting in a café, next to a sunlit window. He’s writing something. At least one of his eyes is focused on us, the viewers. A wine glass is on the table. It probably doesn’t hold a “biscuit Tortoni,” the specialty iced mousse associated with this café. The wine is transparent. The brush strokes are broad, and tactile. It’s amazing how much clarity this impressionist (or pre-post-impressionist) artist gets from these swaths of paint. And maybe it’s the paint itself upon which Manet would most like us to focus our gaze.

This small canvas (slightly more than 10-by-13 inches) used to hang in the crowded little Blue Room on the first floor of the Gardner. Manet, who was only 51 when he died, was in his 40s when he painted "Chez Tortoni" — in his full maturity. He was most famous — or notorious — for larger and more sexually daring works like “Luncheon on the Grass” and “Olympia,” but many of his later, smaller works — a bunch of asparagus, a stick of asparagus, a lemon — are masterpieces. His images of café society — painted with such spontaneity, almost like snapshots — form a kind of social history of demimondaine Paris in the late 19th century. “Chez Tortoni” is a perfect example.

5 Works On Paper

Edgar Degas

1857-1888

Five works on paper by Edgar Degas were stolen from cabinets in the Short Gallery, the passageway that leads into the large Tapestry Room on the Gardner’s second floor. They were stored with other prints and drawings in cabinets designed by Mrs. Gardner herself. Although he began as a painter of Biblical and historical scenes, Degas, like Manet (who was two years his senior), became famous for his depictions of ordinary life — most notably images of dancers, jockeys, and racing horses. The loss of three drawings of scenes with horses is a significant one.

The earliest of the images with horses, “Cortège Sur Une Route Aux Environs De Florence" ("Procession On A Road Near Florence") is a drawing from around 1857, 6-by-8 inches, in pencil and a sepia wash that gives it an antique look. The image is a small procession that shows Degas in a more historical mode. There’s some sort of carriage pulled by a pair of horses (the details are particularly hard to read in reproduction). One of the small but most arresting figures is a woman holding a large umbrella high above three women who seem to be dancing. And there’s an antique view of Florence in the distance.

“Three Mounted Jockeys” (1885-1888) is a larger, less finished ink drawing (about 12-by-9½ inches), with some touches of oil paint. One of the jockeys, the most clearly visible, is in a striking position on the horse, leaning back with one foot in the stirrups and the other leg stretched out around the horse’s neck. The other two jockeys on this sketch page are harder to see because they’re upside down.

Perhaps the most important of the stolen Degas is a small watercolor (date unknown), “La Sortie Du Pesage” ("Leaving The Paddock"), which shows two horses and their jockeys lining up and being led into the track, surrounded by bystanders — quite a crowd for a picture only 4-by-6 inches. Fascinating changes of position are evident from the still visible pencil drawing. The vibrant brown-orange jacket and cap of the jockey closest to the viewer, in a drawing mainly brown except for the whites of the jockeys’ britches, is the major focus of our attention.

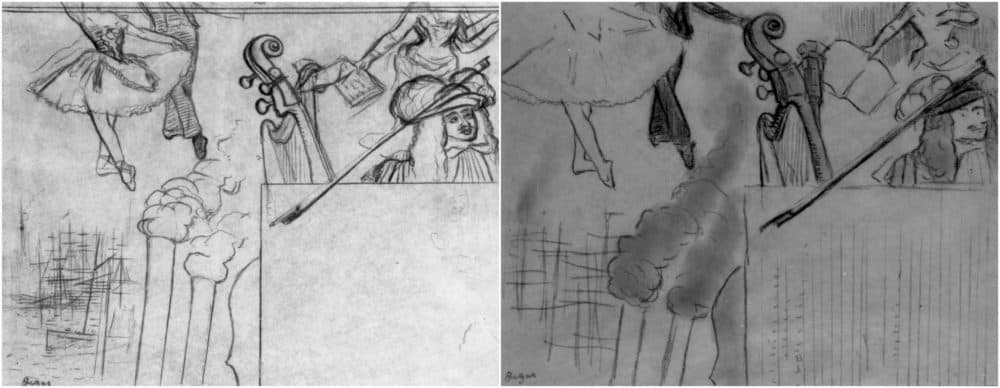

The final two missing works by Degas are a pair of 12-by-8-inch charcoal sketches from 1884, both studies for a program “for an artistic soiree,” one a little more finished than the other. A square in the lower right-hand corner is left blank, presumably the space for information about the soiree. The figures surrounding the empty space include a dancing couple pointing their toes (the woman in a tutu and toe shoes), a woman holding bound pages in one hand (ironically, in the sketchier version, she’s more clearly a singer holding a score), the upper body of a man in an 18th-century hat and wig, sailing ships in a harbor (so sketchy in the less finished version it’s impossible to tell what the drawn lines represent), two smokestacks belching smoke, a harp partially concealing a bass fiddle behind it, with the fiddle bow illusionistically drawn over (rather than behind) the upper part of the blank square. These pages are both charming and puzzling. What kind of fun soiree would such disparate images suggest?

A Bronze Eagle Finial

French

1813–1814

The Oxford Dictionary defines a finial as an ornament at the top, end or corner of an object. The 10-inch tall bronze eagle that was stolen from the Gardner formed the decorative top of a flagpole to which was attached a silk flag from Napoleon’s First Regiment of Imperial Guard. The eagle stands proud, with its wings spread, almost glaring. Although they tried, the thieves were unable to remove the entire flag, which was in a case screwed to the wall of the Short Gallery, so they finally settled for the finial. The entire object hung in Mrs. Gardner’s Beacon Street house before she built the museum. The finial is gone, but the flag is still there.

An Ancient Chinese Gu

1200–1100 B.C.

According to the Gardner Museum website, this 10-inch tall ancient Shang dynasty bronze beaker was one of the oldest objects in the entire collection, and by far the oldest of the stolen objects. Mrs. Gardner bought it in 1922 for $17,500 and placed it in the Dutch Room on a small table in front of Zurburán’s “Doctor of Law,” the painting just to the right of the stolen Rembrandt seascape. The austere trumpet-shaped cup of the beaker is supported by a stem and base overwrought with more intricate interweaving. It was surely one of the most elegant pieces in the entire museum.