Advertisement

Get It While It Lasts! The Museum Of Capitalism Arrives In Boston

Sometime in the future, we’ll all look back on what used to be. And what used to be are Trump tchotchkes, packaging materials from a mountain of Amazon deliveries, “Coal = Jobs” baseball hats and protest signs imploring that you “Keep a slice of the ‘bread’ in your community.”

These are the artifacts of capitalism, the detritus of our home-delivered, Make-America-Great-Again lives. Great wealth lives alongside abject poverty, but we’re all brought together by one simple motive — the profit motive.

In the future, though, perhaps we will have moved onto something else. Exactly what is yet to be determined.

And this is where The Museum of Capitalism comes in, preserving, as it does, the “material evidence, art, and artifacts of capitalism” in an effort to educate “this generation and future generations about the history, philosophy, and legacy of capitalism through exhibitions, research, publication and collecting,” as described on the museum’s website.

The museum is actually a semi-fictional exercise, an “idea” of a museum that examines the nooks and crannies of capitalism as seen from some future vista after the whole thing has blown over. It is the brainchild of the artist collaborative Fictilis consisting of Andrea Steves and Timothy Furstnau, two Oakland-based artists who, back in 2017, mounted a full-scale exhibit looking at the economic system that we’ve come to accept, often unquestioningly, as the normal course of affairs.

But who says it’s the normal state of affairs? Furstnau’s point of view is that right here, right now, is the perfect time to assess what we’re doing and why.

“There are a lot of really basic ways that young people in the United States are not really taught about capitalism,” he says. “There’s an economic literacy that needs to happen across the political spectrum.”

The Museum of Capitalism is now coming to Boston thanks to Abigail Satinsky, a curator at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University, where the exhibit will be on view at the Grossman Gallery through Oct. 25.

According to Satinsky, the museum was designed to analyze capitalism from different angles, “so that you can historicize it, you can study it, you can think about it, and then you can think about alternative futures.”

In its first iteration, the museum opened in the Jack London neighborhood in downtown Oakland in a vacant space that had sat empty following the 2008 financial crisis. The building itself became part of the exhibit, standing as a testament to the boom-and-bust gentrification that swept the neighborhood. Funded by a $215,000 award from the Emily Hall Tremaine Foundation, more than 80 artists, joined by historians and economists, created exhibits dealing with all aspects of daily life in our capitalist system, from ecological concerns to police violence, racism and more. Artists were encouraged to not only mount exhibitions that would explore topics surrounding capitalism, but to bring in the artifacts of capitalism too.

And so, Chicago artist Marc Fischer donated a souvenir “Trump’s Castle” tape measure found while he was cleaning out his deceased aunt’s Philadelphia apartment. A “Made in Korea” sticker reveals the true origins of the patriotic souvenir that the aunt had picked up, despite the fact that she had no great love of Trump.

Artist James McAnally donated a baseball cap adorned with the words “Coal = Jobs.” The placard accompanying the cap notes that “while most baseball caps bore the names of logos of sports teams, the use of a political slogan on this hat suggests the ways politics itself, especially in the American two-party system, was a kind of sport, with supporters of each 'side' of a contest rooting for their team to win. In this case, the political lobby on display is the American Coalition for Clean Coal Electricity (ACCCE), an industry group that sought to rebrand coal as a clean energy source, spending over $35 million in 2008 to mount a major public relations campaign designed to promote public awareness of clean coal in the context of the Presidential race.”

In its Boston manifestation, Satinsky has used the fact that the exhibit is being hosted at an art school to spark a conversation of a slightly different sort from that which took place in Oakland.

“I think it's a very site responsive project,” she says. “When it had its first iteration it was really about the gentrification of Oakland and being in this empty mall space heightens those conversations. And here, we are an art school situated right next to a museum (the MFA). What is the dialogue that can happen across those two spaces? How can we think critically about the museum itself by siting it here with an art school and imagining what artists want museums to be, what they want them to reflect?”

The Boston version is pared down, featuring only 20 artists. Though this version has a slightly different feel from the first exhibit, most of what’s on view comes directly from the original.

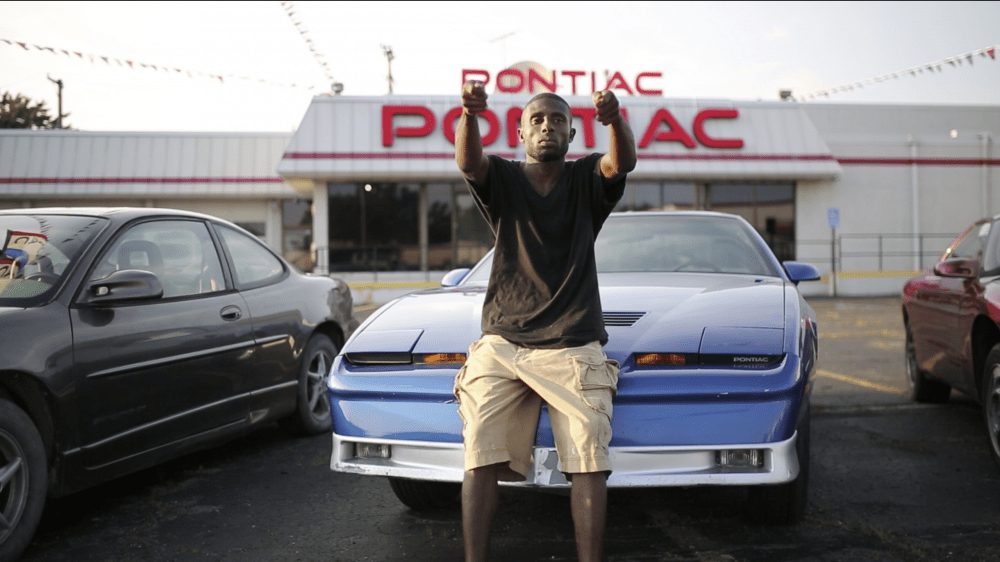

Jesse Sugarmann explores the precarious nature of the auto industry in a three-channel 2013 video work entitled “We Build Excitement” featuring laid-off assembly line workers and car accident victims who recreate the movements of their former jobs and crashes in the parking lot of a defunct Pontiac dealership. The work acts as a sort of homage to both the birth and death of the automobile.

Kate Haug’s “News Today: A History of the Poor People’s Campaign in Real Time” recounts the story of the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign, Martin Luther King Jr.’s last monumental social protest prior to his assassination, using news photographs, memorabilia, reconstructed objects and original documents picked up on eBay. The Poor People’s Campaign culminated with a 3,000-person shanty town named Resurrection City, constructed on the National Mall in Washington D.C., which would foreshadow the Occupy Movement decades later.

Also from the original exhibit is Kelly Jazvac’s “Plastiglomerates” a display of ready-made objects and plastic-based artworks based on a new type of “stone” that Jazvac has documented along with oceanographer Charles Moore and geologist Patricia Corcoran. The three journeyed to Kamilo Beach, Hawaii in 2013 to study the mix of molten plastic debris and beach sediment that they have dubbed “plastiglomerate.”

But there are new additions in this Boston version.

Maia Chao, a Providence-based artist, has created a wall installation of thermoform packaging. It’s the kind of packaging that you find around eggs in the grocery store or around those golf balls just delivered to your house by UPS. There’s a lot of ecological and social implications to this packaging, including the fact, Chao says, that they reflect gendered stereotypes of consumption.

Michelle de la Vega is an Oakland artist who created “Dream House,” a work of hundreds of sewn paper pillows made from photocopies of her father’s architectural drawings. Her father was an immigrant and Korean War veteran who suffered from PTSD. Drawing up plans for his dream home, despite financial pressures and housing displacement, was his way of coping.

All of these works are on display in a city which has itself been shaken by an earthquake of capitalism in recent decades, and, in particular, by the temblors of high tech, big pharma and big money which have all dramatically blunted the city’s artsy edge.

“We live in a city that has one of the highest wealth disparities by race in the country,” says Satinsky. “I think that we are living in a heightened capitalism here in Boston. And so, what the artists are talking about is really resonant with the living conditions of the city.”

The exhibit will host two roundtable discussions, one around the history, economics and political science of capitalism, the other around affordable housing in Boston. This last issue is especially close to the heart of Satinsky, who grew up in Jamaica Plain as the daughter of a housing rights activist.

After the museum has concluded its Boston run, it will move to The New School in New York, where Steves and Furstnau are scheduled to co-teach a class this coming winter in the Capitalism Studies department.

“We’re trying to avoid facile, knee-jerk interpretations,” says Furstnau of the museum. “I hope that the subtleties and complexities of the works and the entire exhibition do that in their own way.”

“It's a museum as a performative act,” says Satinsky. Hopefully, she says, “it can speak to the present and imagine a future for Boston that encompasses an opportunity for all sorts of people of different classes.”

The Museum of Capitalism runs from Aug. 29 to Oct. 25 in the Grossman Gallery at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University. Opening reception is Wednesday, Sept. 12, from 6 to 8 p.m. at the Anderson Auditorium. A panel discussion will be held on Friday, Sept. 14, from 12:30 to 2 p.m. and a “community conversation” on housing in Boston will be held Tuesday, Oct. 16, from 12:30 to 2 p.m. — both at Tufts' Anderson Auditorium.