Advertisement

The Banjo’s Beauty, And Its Cultural Baggage, Is On Display In A New Digital Museum

Resume

Marc Fields and his production team are inside historian and collector Jim Bollman's storied Arlington home. They know the drill by now. This time, Bollman sits patiently on a stool with his rare, pre-Civil War banjo balanced on his knee as they set up their shot.

“This room has more banjo history packed per square inch than any place on earth,” Fields said. “It’s a place I came to when I first started this project and realized how much there is about the banjo which people don’t know about and which people should know about.”

Fields said Bollman's trove of 200-plus instruments, banjo-related artifacts and cabinets of research provide a unique portal into America’s past.

For more than 15 years, Fields has been on a quest to capture, share and contextualize banjo history. Now his work is on display in a new museum. But you don’t need to leave the couch to visit because Fields’ archive-in-the-making, called The Banjo Project, is all online.

The day’s video shoot will be folded into a video of Bollman for The Banjo Project. The self-described "banjophile" is thrilled Fields' museum will allow him to share his life's work with a lot more people.

“Being an old fuddy-duddy, and being electronically challenged, all my information is on three-by-five cards in the collection,” Bollman said, laughing, “and yet he can bring that to the digital age.”

But it's pretty shocking to confront the physical pieces of banjo history lining Bollman's shelves and living room walls. Minstrel-era iconography is everywhere. There are posters, photographs and figurines featuring racist and vulgar caricatures of enslaved Africans playing banjos.

“The banjo is an African-origined instrument — that’s how it started,” Bollman said. “It's an unpleasant part of the history — the diaspora and slavery — but it's the banjo's history. So I know I try to deal with it as carefully and in as non-offensive a way as possible.”

Fields is trying to do the same as he preserves and curates some complicated history in his banjo museum.

“I think we’re right to feel uncomfortable about it,” he said. “Let’s face it, the whole American entertainment industry was founded on the minstrel show. For better or for worse, that’s a good starting place for understanding a lot of things that have happened since then.”

The Banjo Project prototype is online now. Back in his office at Emerson College, Fields clicks through the website on his computer. In one section, there's a deftly-produced HD video that dives into how white minstrel entertainers co-opted the banjo from slaves from the 1800s into the early 1900s. They donned blackface and created parodies that would endure in popular culture for decades.

Fields interviewed ethnomusicologist Greg Adams for context.

“You can’t talk about the history of the banjo, if you can’t talk about racism, slavery, misogyny, appropriation, exploitation — all of the things that run counter to what we love about the banjo,” Adams said.

As a whole, The Banjo Project celebrates the banjo’s beauty while tackling its cultural baggage. Through the site, Fields traces the instrument’s heritage to present day using an interactive interface. His crew is designing dynamic timelines, maps and multimedia narratives. They’ve scanned the rooms in Bollman’s house and a bunch of his antique banjos in 3D.

“You can you can look at the detail all the way down to the grain of the wood, the brackets, the hardware,” Fields explained. Then he does something you'd never be able to do in most museums — he flips the instrument over so we can see the maker’s signature on its back.

In the digital museum, scholars, makers and contemporary performers chime in, including Rhiannon Giddens, co-founder of the Carolina Chocolate Drops. In one video, she says, “There’s so much history in this music that is not in public view — the good stuff and the bad stuff.”

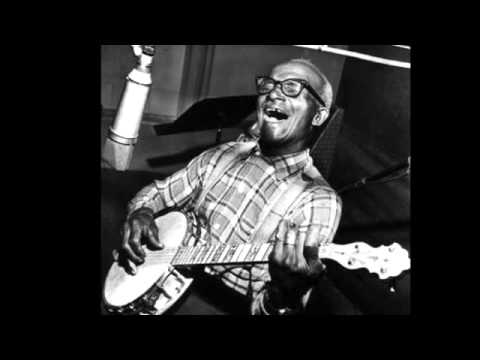

Some of the good stuff is how the instrument has also been a tool for liberation, as scholar Rex Ellis of the National Museum of African American History and Culture points out. Fields clicked over to his reflections on Gus Cannon. Born on a Mississippi plantation in 1883, this itinerant laborer mastered the banjo and went on to compose, record and popularize jug band music.

“So now the banjo not only becomes something that he can express himself culturally with, it becomes something he can use to communicate who he is, it also can become something that gives him upward mobility,” Ellis said.

Cannon’s song, “Walk Right In,” became an international hit in the 1960s.

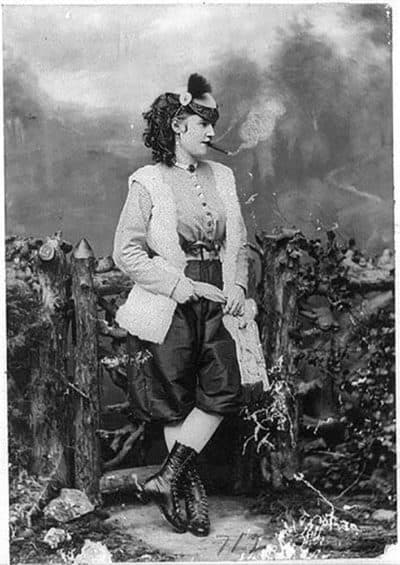

The banjo was also a ticket to a more independent life for child performer Lotta Crabtree. She got her start entertaining miners during the California Gold Rush.

“She was known for never having married, wearing trousers on stage, smoking cigarettes and playing the banjo,” Fields said. She pushed the limits of what was considered fashionable and acceptable for respectable women at the time. Crabtree died a millionaire, right here in Massachusetts, and Fields explained how as a 19th-century female superstar she helped transition the banjo from “the saloon to the salon.” Leisure class whites began to embrace the instrument, elevating it into something they saw as more refined.

“And at the same time they started re-writing the history of the banjo to kind of minimize its black origins,” Fields said.

The banjo's complex and fascinating social history has been revealing itself over time to The Banjo Museum's project manager Shaun Clarke. He's worked with Fields for more than a decade and is also an Emerson College professor.

“So the first time that I saw a woman who was playing the banjo, the first time I saw a black banjo player, that was a challenge to the stereotypes that I had associated with the instrument,” Clarke said.

Some longstanding stereotypes have dismissed the banjo as backwoods or unsophisticated.

Bollman said he’s come up against those ideas plenty of times.

“The banjo is the brunt of jokes, and we think of it as being this sort of déclassé instrument,” he said, “and yet it has this wide, amazing history where at the turn of the 20th century, it was one of the most popular parlor instruments for middle- and upper-class people. Every prep school — both male and female — had banjo clubs, and the instrument went from the minstrel hall to Carnegie Hall.”

Of course pillars of jazz, folk and bluegrass are represented in The Banjo Project. Fields was able to film icons Earl Scruggs and Ralph Stanley before they died, along with others still very much alive, including blues player Taj Mahal.

Fields recalls asking the legendary musician about the banjo’s problematic roots.

“Taj said to me, ‘If you want to heal, you've gotta deal,' ” Fields remembered.

The banjo’s story is still evolving, and Fields will continue to track it. He says a new generation of musicians is reclaiming the instrument’s power with full awareness of its pained past.

Even with years of research under his belt, Fields feels like he’s barely scratched the surface. He'll be able to dig deeper now with a $100,000 grant he and Emerson College received last year from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Fields and his team hope to launch a much fuller version of “The Banjo Project” in the fall, but curious folks looking to get to know the banjo better can visit the museum online right now.

This segment aired on April 17, 2019.