Advertisement

Commentary

59 Years Later, Federico Fellini's 'La Dolce Vita' Still Feels Fresh

Federico Fellini’s 1960 masterpiece “La Dolce Vita” is the pivot point between his gritty, early neorealist efforts like “I Vitelloni” and “La Strada” and later, phantasmagoric carnivals such as “8½” and “Amarcord.” The film is set in actual Rome locations but was shot upon the soundstages of Italy’s Cinecittà Studios, lending a slight shimmer of artifice to the proceedings that would become more exaggerated in the filmmaker’s work as years went on. This flourish fits the content perfectly here, as “La Dolce Vita” is about the search for authenticity in an artificial world, our jaded society reporter Marcello (Marcello Mastroianni) wallowing with the rich and beautiful in this “sweet life” of never-ending parties and decadent dead ends.

The movie — which plays all weekend on 35mm at the Brattle Theatre — doesn’t seem to screen around here as often as it used to, and lately, I’ve been getting the vibe that Fellini has lost a bit of his luster in cinema studies circles. To some extent I can understand; mid-century Italian films, in general, tend to be characterized by a robust sensuality that’s fallen out of fashion with younger audiences. (The keyword here is “indulgent.”) Fellini’s apparently inexhaustible fixation on boobs and butts is about as “male gaze-y” as movies get, and all his tortured Catholicism is probably pretty passé.

Yet every time I watch “La Dolce Vita,” I am struck once again by how modern this 59-year-old film feels, maybe not in its costumes or sexual politics but more in its existential malaise and the seductiveness of a vapid celebrity culture gone to seed. After all, Marcello’s buzzard-like photographer sidekick Paparazzo inspired the nickname of a profession that’s still thriving today, and indeed Fellini’s revelers on the Via Veneto could quite easily be updated as Instagram influencers, rolling on molly instead of red wine while taking selfies in the Trevi Fountain. It’s not much of a stretch to imagine Marcello as a TMZ blogger puttering around the fringes of the Fyre Festival, except rather than chain-smoking he’d probably vape. Some emptiness is eternal.

Unconcerned with the drive of a conventional plot, “La Dolce Vita” watches seven nights become seven mornings, with episodic interludes intentionally echoing one another in provocative, sometimes blasphemous ways, the scared alternating with the profane. The iconic opening shot finds a soaring statue of Jesus carried by helicopter over the streets of Rome en route to the Vatican, while Marcello and Paparrazo follow in a chopper close behind, trying to get the phone numbers of sunbathing beauties on the rooftops. (The Catholic Church was predictably displeased with the entire picture but singled out this sequence in particular, considering it a parody of Christ’s resurrection.)

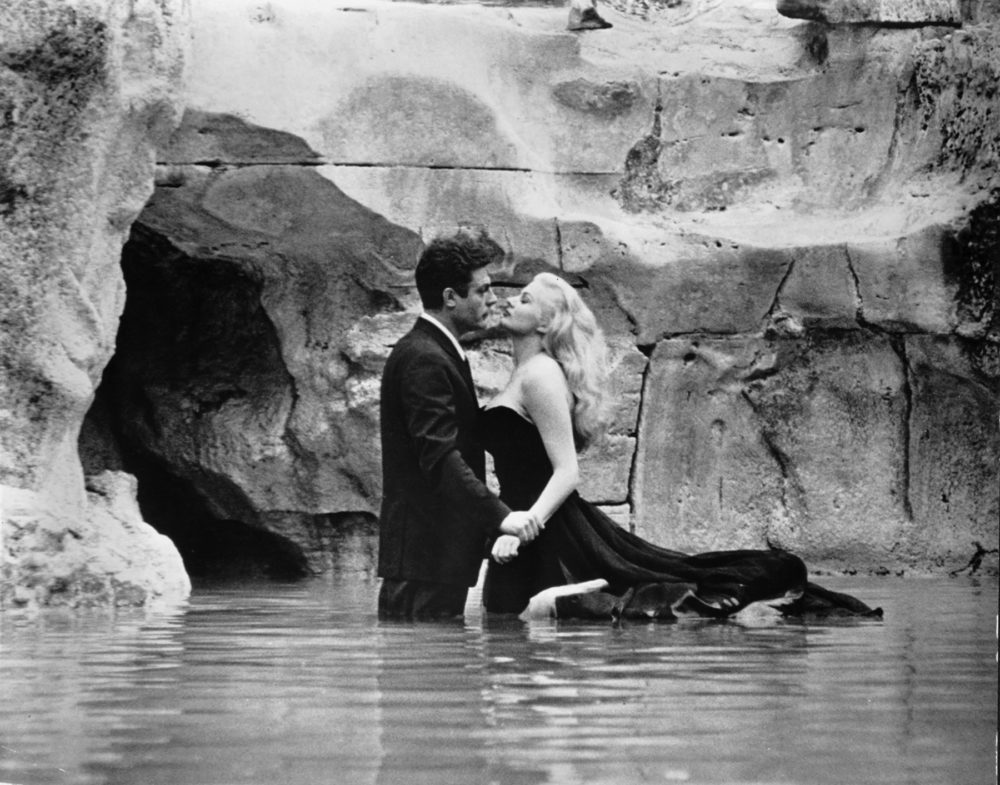

The movie is structured as a series of ascents and descents, Marcello sneaking down to a prostitute’s basement apartment for an illicit assignation with Anouk Amiée’s bored heiress, Maddalena (clock that name!), or racing up to the top of St. Peter’s Basilica in pursuit of Anita Ekberg’s almost cartoonishly voluptuous Swedish movie star, Sylvia. The madcap manner in which reporters swarm the spirited actress is replayed and revised a few scenes later, when two peasant children claim to have seen a vision of the Madonna and lead the press on a wild goose chase, with devastating results.

The dashing, sad-eyed Mastroianni had a unique screen presence that seemed to be lit from within by a twinkle of amusement. He was one of the movies’ lightest brooders and, when acting as an avatar for Fellini in their collaborations, brought a boyish sense of play to the sometimes morbid self-pity of these oversexed scamps. (He made it all look so easy, but for proof of how difficult it really was watch Daniel Day-Lewis give the worst performance of his career trying to mimic Mastroianni in “Nine,” Rob Marshall’s execrable 2009 musical based on Fellini’s “8 ½.”)

Whether up, down or around, all these pursuits prove ultimately fruitless, whatever the characters are seeking denied in the cruel light of morning. Dawn doesn’t bring a new day in “La Dolce Vita” but rather arrives with abrupt, unhappy endings. The water in the Trevi Fountain stops running, Marcello’s dad humiliates himself with a French showgirl, the one you love leaves with someone else and a ghastly sea beast washes up onshore as carousers cavort into the sunrise.

Marcello wanted to be a real writer once, a person of substance. Whether he got too distracted or just couldn’t hack it is left for us to decide. Yet I daresay that anyone who’s ever spent too long at the party chasing pleasures past the end of the night can’t help but feel deeply for him in the film’s final moments, as a smiling beacon of his squandered promise waves in vain, unrecognized from a distant shore.

“La Dolce Vita” screens at the Brattle Theatre from Friday, Aug. 30 through Monday, Sept. 2.