Advertisement

This Exhibit Showcases The Ingenuity Of Artists Behind Bars

What do you think of when you think of an artist? Do you think of someone creating work behind bars? Or in a cramped cell? Do you think of someone who is banned from using things like stickers, paint, tape and glue?

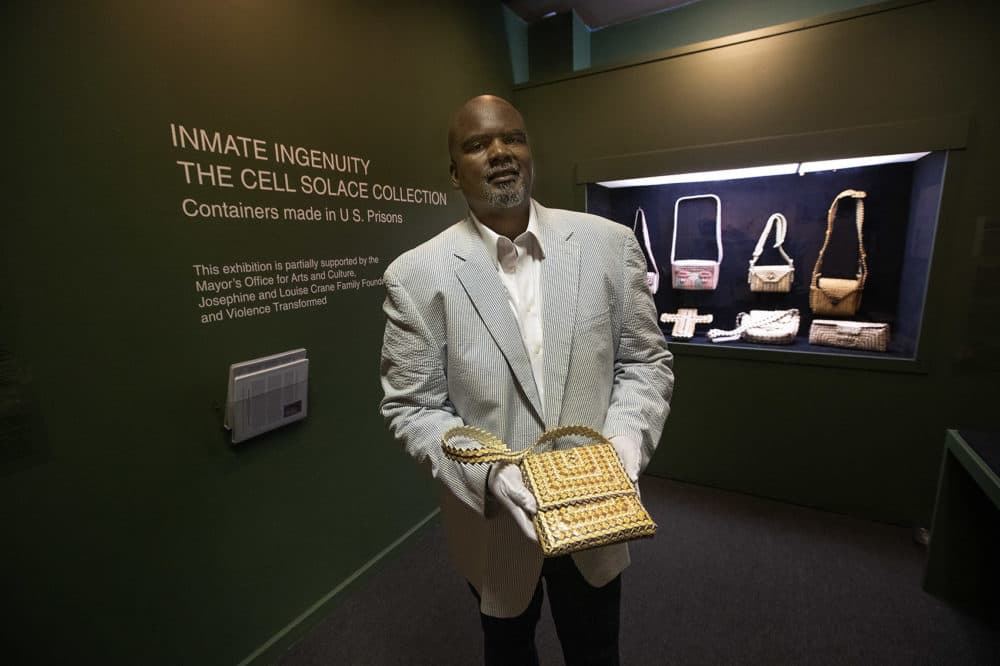

The "Cell Solace Collection" at the Museum of the National Center of Afro-American Artists challenges who we label as artists and what we deem as art. Boston-based musician and artist Antonio Inniss has traveled across the country, from New Mexico to Wisconsin to New York, collecting items crafted by people who were incarcerated. Prisons have extensive bans on materials, including some of the most commonly used in visual art and sculpture. So what exactly are these pieces made of?

Behind the shine of the glass display, the artworks look like they're made of animal skin, maybe snake or alligator. But closer inspection reveals that these bags, belts, jewelry boxes (and more) are painstakingly handcrafted from squares and squares and squares of cigarette boxes. A few are made entirely from postage stamps.

Inniss was introduced to this particular art form growing up in the 1970s. His father, after spending some of his youth in and out of Rikers Island, moved to Boston and stayed in touch with friends who were still in prison. One of them, named Terrence Williams, sent Inniss' father two pieces crafted from cigarette boxes. "One was for my mother and another was for Terrence's girlfriend," Inniss recalls with a smile. "As soon as I saw it, I just fell in love with it."

For him, these pieces represent the power of transformation, of taking small pieces and shaping them into a larger, intricate object. Often times, the pieces Inniss collects were crafted as gifts for loved ones, family members and friends. They're a testament to the strength of humanity, he says.

"The fact that you're locked up," he says, "stripped of your right to creatively express yourself ... and you make something like this anyway? It's full of heart."

Since he first encountered the art form, Inniss has collected 120 pieces that were created in this fashion by incarcerated artists. He finds some in old antique shops and others, he receives directly from the artists or their families. In doing so, he also collects their stories.

"The oldest piece I have is a bag from 1921, made from mostly Raleigh cigarette packs, a brand that was very popular in the early half of the century," he says.

Certain techniques are used to make certain pieces. You can't just fold up a cigarette box and hope it holds its shape.

"There's different variations because you can take one square and fold it different ways," Inniss explains. "They take a cigarette box square and fold it into an inch, a half inch or a quarter inch. The quarter-inch technique is used for more intricate work since it requires a lot more boxes."

Box by box, inch by inch, these dizzily detailed works are built.

"There's so much inherent artistry in these pieces," curator and director of the NCAAA Edmund Barry Gaither says. "Constructing them draws from so many artistic and design disciplines. ... What it really says is that [prison] is filled with people who could've easily had viable careers as artists."

Systemic biases and stigma against incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people has contributed to the perception that their art works are out of place in fine art institutions.

"What we see is that artists who've been or who are incarcerated are often defined by their conviction," says Rachel Corey. She's a co-founder of Freedom Through Art Collective (FTA), a group of 26 creatives who are or were recently incarcerated.

Meagan Smith, another co-founder, elaborates: "Prisons make it extremely difficult for those inside to participate in any art making. In fact, they can receive demerits, or tickets, just for having things like crayons or even glitter."

At the Museum of the National Center of Afro-American Artists, a tour group stop stops to view the exhibit.

"I don't think I've ever seen anything like this," Kristy Mincey remarks. She's visiting from Florida and says she's never seen objects like these in a museum.

Another group member, Desmond Brown, agrees before revealing he works in a prison in Jacksonville, Florida. "I've seen stuff made like this before but never in this fashion. A lot of this stuff is contraband now, it's not even allowed."

Despite strict regulations, the ingenuity of artists behind bars flourishes as they innovate unique ways to source and use materials. While the very act of creation subverts the prison system, the pieces in Inniss' collection weren't created to prove a point about the prison industrial complex. Many of them were birthed out of love, created to fill the physical void formed between those inside prison walls and those on the outside.

"They were for mothers, daughters and sisters," he says. "For friends. They were made to express love in some kind of way. Every item was made to show gratitude."