Advertisement

At The ICA, 'When Home Won’t Let You Stay' Explores The Migration Experience

People are on the move. They move from region to region, country to country, continent to continent. It’s always been that way.

But as the movement of people gains speed and populations move into regions or countries that don’t always welcome them, migration has become a prominent issue in politics, and of late, in art exhibits too.

Now the Institute of Contemporary Art continues the conversation with “When Home Won’t Let You Stay: Migration Through Contemporary Art,” opening Oct. 23 and running through Jan. 26. Featuring 20 artists from more than a dozen countries across Europe, Africa, Asia and the Americas, the exhibit doesn’t dwell on the how or why of migration, but rather resides in the more personal spaces in which artists are free to explore the theme in sometimes very unexpected ways.

“When you listen to stories of migration, there are a number of commonalities that often come up in those stories and those narratives… the issue of the border, the issue of nation, the idea of belonging, home, the sea,” says Ruth Erickson, a curator at the ICA who organized the exhibit with curator Eva Respini. “There are ways in which the works in the exhibition talk to one another because they share some of this common ground.”

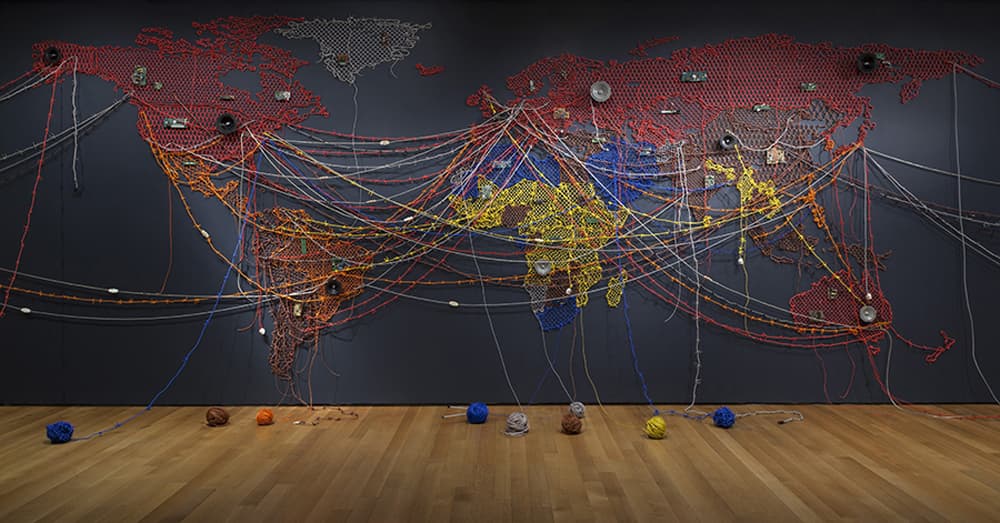

The artists in this exhibition work in sculpture, installation, painting and video. The work on view was made since 2000 and some of the pieces are quite large. (A video installation by British artist and filmmaker Isaac Julien fills an entire room, as does another video installation by Irish artist Richard Mosse and a sculptural installation by British artist Yinka Shonibare CBE.)

“In that sense, we really wanted to privilege the individual artist's voice with these larger works that stand on their own two feet in terms of, not just their scale, but also their ambition,” says Respini.

Camilo Ontiveros, a Mexican-born artist now living in Los Angeles, creates sculptures out of found materials. In his piece “Temporary Storage: The Belonging of Juan Manuel Montes,” Ontiveros bundles together a TV, a bed, books, a desk chair, tennis racket and clothing — the furnishings of a bedroom occupied by Juan Manuel Montes before his deportation to Mexico from the United States in 2017. Montes had been protected under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals policy but became the first person to be deported by the Trump administration. The forlorn and haphazard bundle of materials speaks palpably to loss and precarity, displacement and impermanence. Ontiveros says it recalls his own experience, which is what drew him to Montes’ story.

“I see a reflection of me,” he was quoted saying in a 2017 Los Angeles Times article. “I was here illegally. I went through the same kinds of fears growing up. I was a student. I went to college.”

Similar to Ontiveros but with a different experience is Mona Hatoum, a British Palestinian born in Lebanon who has made a “sense of dislocation” a prominent theme of her work. Like Ontiveros, she also often incorporates everyday found objects, as she does in “Exodus II.” Two simple leather suitcases, one green, the other yellow, appear to be growing hair that seems to spill out of each side panel and entangle. The luggage suggests movement and travel, while the hair hints at remnants of the human lives contained within the suitcases. The viewer is called to imagine what gets left behind when anyone migrates, either voluntarily or as a refugee.

“We usually expect furniture to be about giving support and comfort to the body,” Hatoum told artist Janine Antoni in a 1998 interview in Bomb Magazine. “If these objects become either unstable or threatening, they become a reference to our fragility.”

Korean artist Do Ho Suh is instead interested in physical spaces and memory, or how, as he has said, “your house gets inside of you.” Born in Seoul and now living and working in London, New York and his hometown, he presents a series of fabric sculptures that are one-to-one scale replicas of the rooms within the many places he has called home. He uses pale, transparent fabric in pink, yellow and green which are ephemeral, ghostly and beautiful — just as are our memories of home.

“As we all move around from one country to another, from one city to another and from one space to another, we are always crossing boundaries of all sorts. . . And with this constant passing through spaces, I wonder how much of one’s own space one carries along with oneself,” he told the Washington Post in 2018.

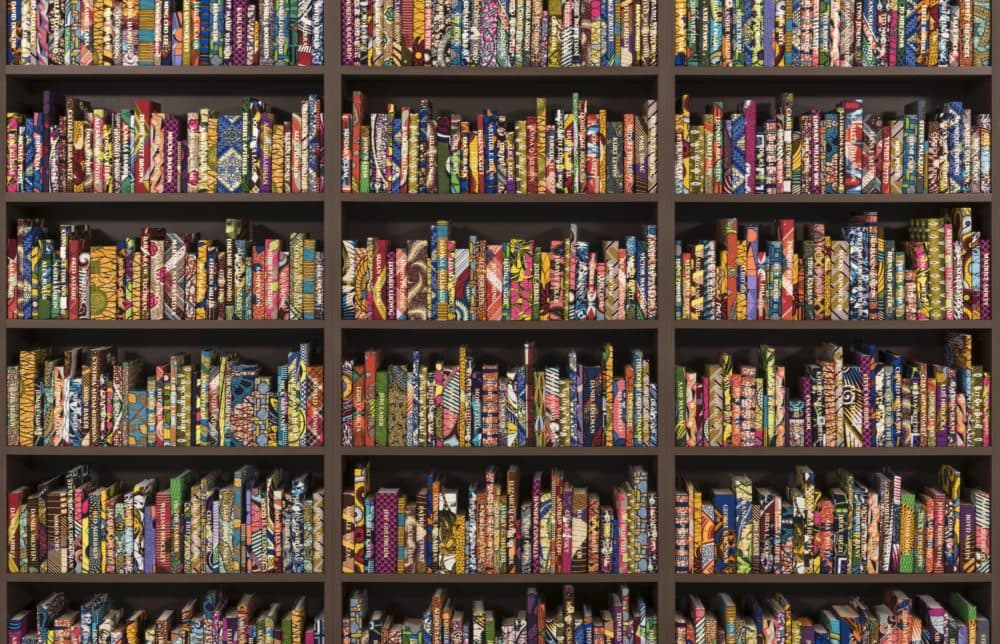

Yinka Shonibare CBE also creates installations, usually referencing the hybridity of a globalized world. Shonibare was born in Britain but raised in Lagos, Nigeria. In “The American Library” (2018), he wraps 6,000 books in vibrant Dutch wax print fabric. The books’ spines bear the names of first- and second-generation immigrants to the U.S., as well as the names of descendants who migrated from the South to the North or West during the Great Migration of African Americans in the first half of the 20th century. The piece stands as a memorial to all those who have made a mark on American culture, ranging from W.E.B. Du Bois to Toni Morrison, Grace Lee Boggs to Steve Jobs. While in some ways the installation is optimistic, speaking to multicultural ingenuity, it also has more ambiguous intimations, as each volume in the library is wrapped in a colonial trade good, and one of the names on a volume belongs to Donald Trump.

“I like the fact that the fabrics are multilayered,” Shonibare told Art 21. “They have this interesting history that goes back to Indonesia. And then they’re appropriated by Africa and now represent African identities. Things are not always what they seem ... I enjoy working with that.”

In many ways, mounting this exhibit posed a challenge. The migration theme is well-worn territory at this point, with exhibits on migration and displacement running in museums and galleries across the country as well as across town. (The well-received “The Warmth of Other Suns” ended a run at the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. last month, while another migration exhibit entitled “Crossing Lines, Constructing Home” is currently on view at the Harvard Art Museums through Jan. 5.) Not only does this present a challenge in presenting a fresh perspective, but there is also the question of what a museum can tell us about a subject that we read and hear about daily.

“We can bring the artists’ perspective,” answers Respini. “I believe really deeply in art's capacity to tell us something about who we are, about our society, but doing it from the perspective of an artist, that journalism can't do or science may not be able to do. It can tell personal stories. It can provide a reflection on something ... create maybe a space of understanding.”

The exhibition’s title, “When Home Won’t Let You Stay,” is drawn from a line in a poem by the Somali-British poet Warsan Shire. The poem was inspired by the stories of refugees, and like some of the art in the exhibit, reflects the sense of desperation that often drives the decision to uproot a life. The poem’s last stanza reads:

No one leaves home until home

is a damp voice in your ear saying

leave, run now, I don’t know what

I’ve become.

From the perspective of artists included in the exhibition, it seems that state of not knowing may continue, long after a migrant has reached his or her final destination.

“When Home Won’t Let You Stay: Migration Through Contemporary Art” is on view at the ICA from Oct. 23 through Jan. 26.