Advertisement

Poet Cameron Awkward-Rich Wants To Decode Truth

Before Cameron Awkward-Rich became a poet, he had been studying to become a scientist. While he worked his lab hours at Wesleyan University, he realized that conducting experiments had many similarities to writing poetry.

“In both realms, I’m interested in questions like, ‘What do we know?’ and ‘How do we know it?’ Just as you might set out to figure out the way muscle patterning works, for example, I wanted to decode the bewildering experience of walking around the world as a black person and as a trans person.”

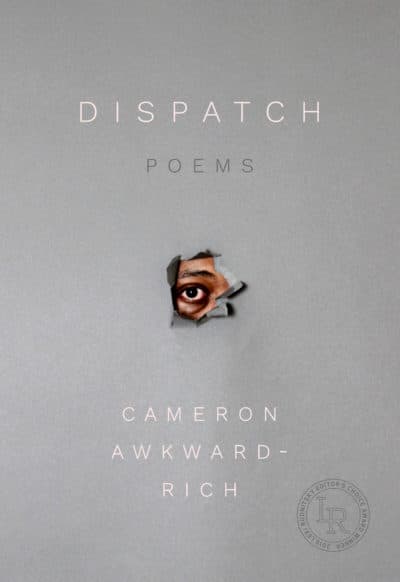

Awkward-Rich’s sophomore poetry collection, “Dispatch,” meditates on these questions in regard to friendship and family, police brutality, historical cases of gender presentation, and more. Each poem is a contained anecdote that blossoms into a larger idea. His spare lines allow breathing room for the gravitas of the vocabulary that makes it to the page — the language itself is just as political as the topics he writes about.

One such question that Awkward-Rich challenges the reader with is how love poems might reflect the reality of love rather than idealization of it. A love poem by any other name would smell as sweet, but Awkward-Rich addresses three “Love Poems” to people who fundamentally misunderstand him — an ex, a proofreader who finds fault in the absence of pronouns, a white woman who misrecognizes black poets. “One of the weird things about traditional love poems is that they tend to treat the beloved as an ideal,” he said. “But there are all kinds of ways, small and big, that love can be an injurious relationship in addition to sustaining one.” So instead of cherishing the flaws of a loved one, he flips the script, and seeks to find sustaining elements to otherwise untenable relationships.

Awkward-Rich has threaded the needle between poetry and science in other interesting ways. As a biology and English double major undergraduate, he wrote a creative thesis about his experience with working in labs. Later, his debut poetry collection “Sympathetic Little Monster” contained a series of poems called “essays,” in which he pondered the difference between an essay and a poem. He said, “A lot of slam poetry is the perfect example of what an essay is. You have your hook, evidence, and then all sorts of things to present ideas.” Both cases are trying to make sense of the world and decode "truth."

As a gender studies professor at UMass Amherst, Awkward-Rich explores how culture and social movements influence what we come to understand as truth. His doctoral dissertation at Stanford compared how trans narratives differed among trans studies, queer studies and feminist studies; disciplines that one might think “would be naturally aligned, but are not always, in key ways.” He said, “the early 2010s was very strange set of years for trans representation in the U.S. because the near absence of such representations suddenly gave way to an abundance,” most notably a TIME cover story about Laverne Cox called “The Transgender Tipping Point. “In those years, I went from having to actively seek out media about trans people, to being unable to avoid it, for better and for worse.” In 2016, Awkward-Rich decided to create his own trans narrative in “Sympathetic Little Monster.”

Awkward-Rich considers “Sympathetic Little Monster” to be a “teenage book” because he wrote it early in his transition. “I was full of teen feelings. I felt utterly bewildered, and this collection is a record of my bewilderment.” He knew his body would be perceived differently after transitioning, but he didn’t know how the world would register his body until it happened.

“Dispatch” opens with two epigraphs to present the collection’s thesis. The first is a racist quotation from Thomas Jefferson claiming that the emotions of black people are not as nuanced as those of white people, as though they are masked by an “immovable veil of black.” The second epigraph is from W.E.B. Du Bois, saying that he has “no desire to tear down that veil,” and therefore “lived above it in a region of blue sky and great wandering shadows.” Similar to how he subverts his “Love Poems,” Awkward-Rich turns Jefferson’s racist idea on its head with the book’s theme of ambivalence, or as he puts it, “what is the injury and what is the sustenance.”

The four poems titled “[Black Feeling]” are riffs on the essay “Feeling Brown, Feeling Down” by scholar José Muñoz, which discusses the ways Latinx people are coded as too melodramatic or too expressive compared to the dominant norms of white people. Although these poems are in response to racist remarks, Awkward-Rich thinks about what can be enabling about being perceived as not properly human. It can be both freeing and debilitating.

Being ignored due to your identity is a double-edged sword. As Laverne Cox said in a 2013 New York Times article, “At the heart of the fight for trans justice is a level of stigma so intense and pervasive that trans folks are often told we don’t exist.” When the Trump administration removed seven words from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website including "transgender,” “diversity" and “vulnerable," it was trying to control what is truth. If a trans person is attacked but you can’t use the word “transgender,” then that violence can’t even be addressed. “The first place violence against people or political systems is going to register in the language,” said Awkward-Rich. “The language we use enables or covers over violence on big scales and small scales… But the only system I know how to tinker with is language.”

In his poetry, and as an assistant professor in his UMass Amherst classrooms, Awkward-Rich said he’s “very much about trying to take what might be hard material and make it relatable but not make it any less complicated.” “It unsettles my students that they may try hard but there’s no right answer. They have to sit in complication. Both my poetry and teaching refuse the catharsis of claiming to know exactly what is up.” But he also knows, “If I start with joke, it makes an idea less scary.”

The last poem in “Dispatch” is “Cento Between the Ending and the End,” which is composed entirely of language from other poems by his friends. “It’s a poem about friendship and about having that kind of collective voice to work with.” The question behind this poem, as well as many poems in the collection that work with found text is: “How do I take something that exists in this world and make it interested in the flourishing of my people?” He also asked rhetorically, “Who knows if it works?”

I can say that it certainly does.