Advertisement

Review

In The A.R.T.'s Musical 'Moby-Dick,' The Whale Is An Extraordinary Sum Of Diverse Parts

In Herman Melville’s iconic 1851 novel “Moby-Dick,” the crew of the Pequod stalks the titular whale for three years. The musical extravaganza “Moby-Dick,” which is in its world premiere by American Repertory Theater (at the Loeb Drama Center through Jan. 12), doesn’t go on that long. But it is an epic undertaking: a three-and-a-half-hours-long, singing and dancing riff on the Pequod as a stand-in for America — whether in the run-up to the Civil War or now, when our melting pot is captained by a megalomaniac.

Stylistically, the work, mirroring the novel, is all over the place, encompassing not just Melville’s allegorical adventure tale but also a vaudeville about whales and whaling, a jazz cycle based on the fate of cabin boy Pip and a profane, religion-bashing stand-up routine by Ahab’s Parsee prophet, Fedallah. As for composer-librettist-lyricist-orchestrator Dave Malloy’s score — lush, dissonant, soaring and melodic — it incorporates influences that range from jazz, folk and country to Broadway and West African polyrhythms that apparently recall the communication of sperm whales.

Malloy, of course, is the genius behind “Natasha, Pierre & The Great Comet of 1812,” which was mounted at the A.R.T. in 2015 after two smaller-scale New York incarnations and before moving to Broadway, where it was nominated for 12 Tony Awards. Not all of Malloy’s works are on so grand a scale; he is also the creator of “Beowulf — A Thousand Years of Baggage,” the spooky song cycle “Ghost Quartet” and, most recently, “Octet,” an a cappella chamber opera about man versus that other great white whale, the internet.

But whereas “Comet” was carved from just 70 pages of “War and Peace,” this show stretches its musical and theatrical arms around the whole eddying enchilada that is “Moby-Dick” — from the eschatological adventure to the odd digressions loathed by student readers. Happily, Malloy is once again abetted by Tony-winning director Rachel Chavkin, with whom he developed the leviathan theater piece, and Tony-winning scenic designer Mimi Lien, who supplied “Comet” with its lavish 19th-century Russian supper club/portrait gallery look. Here she puts us all “in the belly of the whale,” its wavy wooden ribs — also the ribs of the Pequod — encompassing the entirety of the Loeb Drama Center auditorium. The massive, skeletal set is constructed entirely of wood and ropes, with a panel of glaring lights at the curving back wall of the boat that are deployed to dramatic effect.

“Moby-Dick,” as passionately and quirkily unwieldy as the novel, is divided into four parts, plus a prologue and an epilogue. And at the Loeb, it’s clear from the get-go, when Dawn L. Troupe, as Father Mapple in pirate hat and hoop skirt, ascends to the crow’s-nest pulpit to apply her velvety alto to a gospel-infused telling of the Biblical Jonah’s story that we are in gifted musical hands. In whatever euphonious direction Malloy deigns to go, the show’s terrific nine-person band and accomplished cast of singers will carry us there, buoyed by a score that, even when the subject is whale guts, is grandly propulsive and pretty.

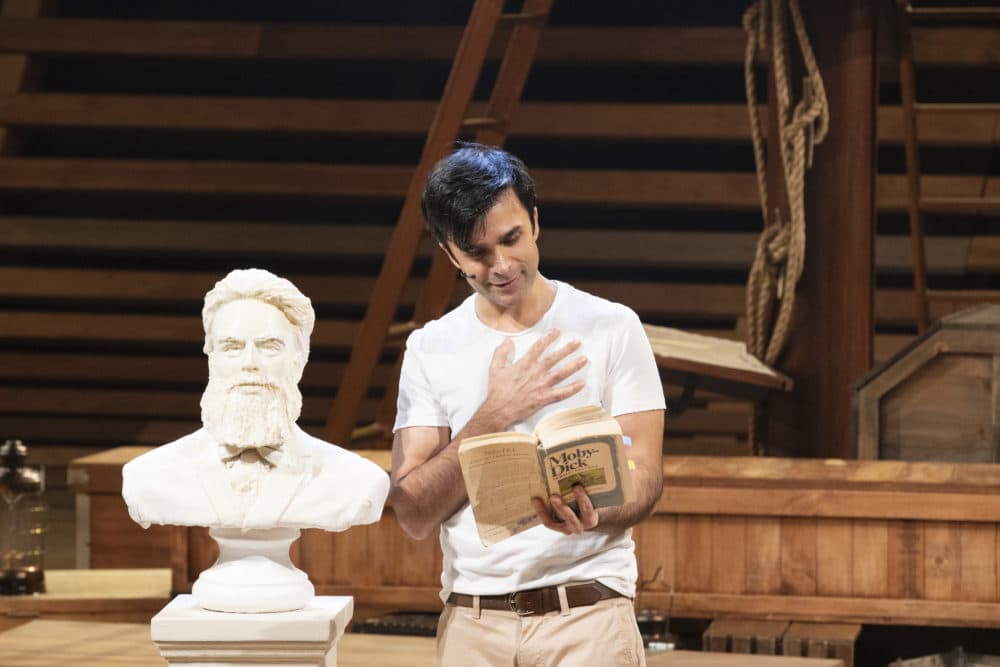

The central, connective devise of the theater piece is that narrator Ishmael, like his discursive tale, has survived into the 21st century. In the geeky, boyish person of the excellent Manik Choksi, he’s clad in a tee, open shirt and khakis and clutches a dog-eared copy of the novel that reminds him “what a beautiful sprawling mess this country can be.” In this guise, the chronicler can underline the enduring American themes of democracy, capitalism, racism, self-aggrandizement and damage to the environment. He can also make whatever modern assertions he likes, from suggesting that Melville was “almost certainly in love” with Nathaniel Hawthorne to confiding that “I just don’t feel safe in this country right now.”

Ishmael also acts as an emcee of sorts, encouraging us to clap for the band and enthusiastically directing the audience-participation portion of the show — in which volunteers are provided with waterproof red parkas and taken by the crew on a low-tech amusement-park approximation of a harpooning foray. (The show mostly eschews flashy bells and whistles, opting instead for pulling ropes and choreographically deploying harpoons as if one’s life depended on it — which, of course, the Pequod crew’s do.)

Advertisement

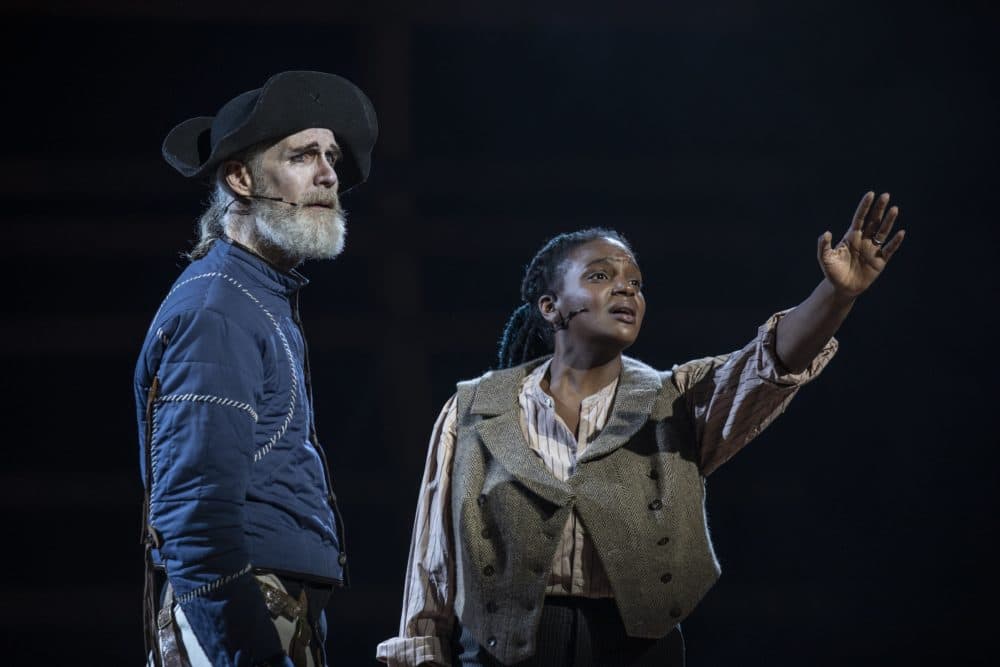

Malloy and Chavkin have taken the diversity of the Pequod’s population even further than Melville did. Captain Ahab, chillingly rendered by a gaunt, bearded and driven Tom Nelis, is the only white man on board the ship. The mates, Starbuck, Stubb and Flask, are all portrayed by women of color (Fedallah makes sure we get that they are supposed to be “white dudes”), as is cabin boy Pip. As in the novel, the harpooners are — and are played by — men of color. That the Captain, described by Fedallah as an “old Quaker gone crackers,” egoistically leads them to their doom is hardly a point that needs hammering.

“Part I: The Doubloon” introduces the crew of the Pequod, including moral compass Starbuck, Stubb and Flask, as well as the more exotic harpooners: South Sea Islander Queequeg, Native American Tashtego and African Daggoo. It then deploys a catchy number to treat Ishmael’s polite reluctance to “sleep with a cannibal” before establishing the tender homoerotic connection between Ishmael and his tattooed bedfellow and making an urgent, active set piece out of Ahab’s pre-story. At last the gnarled, limping Captain appears to nail his “ounce of gold” to the mast and snare the crew into his revenge-crazed quest to destroy the crook-jawed white whale that made a nosh of his leg.

Part II, titled “The Honour and Glory of Whaling,” is the strangest part of the piece. This is where Malloy sets out to make vaudeville routines out of some of the novel’s more eccentric, even pedantic digressions. These include the chapter titled “Cetology,” in which Ishmael’s cataloging of the various types of whales takes the form of a puppet parade whose participants are all constructed from detritus pulled from the sea, and “The Whale as a Dish,” a dexterous turn in which Stubb extolls the gustatory pleasures of whale steak. Apparently Malloy adores these chapters and doesn’t mean to make fun of them. But that’s a hard line to draw in the blubber.

The more somber second half of the show, though, is almost unremittingly gorgeous, beginning with the poignant if tambourine-driven suite of jazz songs that set the smallness of Pip (a touching Morgan Siobhan Green) against the vastness of the ocean. From there on, the work becomes more otherworldly, with Ishmael and Queequeg mordantly dancing as the Pequod drifts further from reality and Ahab going down fighting “thou all-destroying but unconquering whale.”

Chavkin, of course, is more than the director; she and Malloy have developed the piece in tandem. Still, abetted by musical director Or Matias and choreographer Chanel DaSilva, she keeps the show moving forward even when it’s dallying or jigging in place. And I can’t say enough about the ensemble, which includes several veterans of past Malloy-Chavkin projects. Especially striking are Starr Busby’s strong, sweet-voiced Starbuck, whose connection to Ahab is palpable, and Kalyn West’s nimble, antic Stubb. As Fedallah, Eric Berryman deftly straddles the line between Parsee prophet and Richard Pryor and gives magisterial voice to the character’s eerie prognostications, uttered near the end of the first act and then again as the two “American hearses” gear up their engines of inevitability.

This marks the unveiling of “Moby-Dick,” which has been several years in the making. Its music is both wonderful and well rendered. True, a few of the whimsical detours are jarring, even silly, and the piece is awfully long. Some cutting might prove judicious — though, please, not of the ropes that bind Malloy and Chavkin to “Moby-Dick.” The duo is closer to scoring the whale than Ahab ever was.

The A.R.T’s production of “Moby-Dick” continues at the Loeb Drama Center through Jan. 12.