Advertisement

Jacob Lawrence's 'The American Struggle' Commits The Nameless To Canvas

An exhibition of painter Jacob Lawrence is a searing indictment of methodical erasures in our history, and a call to recommit to the democratic principles of liberty and justice for all.

"Jacob Lawrence: The American Struggle" is the first museum exhibition of the artist’s tempera panels from his monumental 1954-56 series "Struggle: From the History of the American People" (on view at the Peabody Essex Museum through April 26). Set alongside contemporary works by Hank Willis Thomas, Derrick Adams, and Bethany Collins, Lawrence’s work reads louder and truer than ever.

Lawrence’s subtle rewriting of classic tropes of American history makes room for women, black people and Native Americans, whose contributions to the fight for freedom are rarely given their due. For Lawrence, rather than the traditional parade of great white men, national glory rested instead on the shoulders of thousands of nameless foot soldiers, diplomats, laborers, cooks and cleaners, as well as the involuntarily displaced and exploited indigenous population: an anonymous grouping of unsung heroes.

Lawrence broke the human figure down into its composite shapes, reducing gradations of shade and hue to pure, saturated colors with minimal modeling. He mixed his own paints, ensuring color consistency throughout a series by applying one color at a time to each panel in the series before moving on to the next. Visible brushstrokes and clashing, forceful lines imbue Lawrence's work with frenetic energy.

"Struggle" turns textbook tropes on their heads: one panel shows the iconic scene of Washington crossing the Delaware, but from an inverted perspective. The painting upends the familiar image of Emanuel Leutze’s 1851 painting, where a dramatic composition highlights Washington’s profile as he stands aloft in the tiny boat, stoically leading his men into unknown territory.

No central figure emerges in Lawrence’s version: a cluster of men, huddled under blankets, spears held aloft, wait out the perilous journey, blood dripping from the hulls of their boats to signify the danger and sacrifice inherent in their mission. It’s a behind the scenes look at one of the fundamental legends of American history, drawing back the curtain to reveal those who made the legend possible.

Lawrence wrote that his aim for the series was to “depict the struggles of a people to create a nation and their attempt to build a democracy.” His panels align the trials and achievements of marginalized Americans with well-known stories of American history, subtly eliciting an empathetic response from the viewer.

We achieved liberty from Great Britain, Lawrence suggests, but many Americans still face the same obstacles to freedom as the Founding Fathers—the struggle continues. This universality is perhaps the most powerful aspect of the Struggle series: the comparisons Lawrence makes feel fresh and vital and necessary, nearly 70 years after they were painted.

Lawrence, who was born in 1917, spent his early years chronicling black history. He created series depicting the lives of Harriet Tubman, Toussaint L’Ouverture and Frederick Douglass, among others. He was only 23 when the Museum of Modern Art bought his 1941 "Migration Series," chronicling the movement of African Americans to the Northeast and Midwest following the first World War. It was the first work by an African American artist MoMA had ever purchased. Lawrence’s masterful use of bright colors and ‘dynamic cubism’ reminded contemporary viewers of Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, the spoonful of sugar helping viewers to digest the underlying narrative of the lived experience of marginalized Americans.

As a 21st century audience, we have an obligation to be drawn beyond the surface of Lawrence’s work, to examine our own history and learn the lessons Lawrence sets out — but the striking beauty of his painting, the vibrant colors and powerful compositions, retain their impact.

The three contemporary artists chosen to accompany the Struggle series are thoughtful responses to the themes of Lawrence’s work. Hank Willis Thomas, a photographer and multimedia artist, provides perhaps the most engaging addition: a pair of images that reveal different images to the naked eye and beneath the flash of a cell phone camera. As I stood in the gallery, I watched a parade of viewers uncover the hidden images, the thrill of participation and discovery cushioning the troubling scenes.

Bethany Collins’ 2017 "America: A Hymnal" can be heard throughout the gallery, an eerie soundtrack to the exhibition. Collins collected 100 iterations of the song “My Country Tis of Thee,” playing them simultaneously, an unsettling demonstration of our changing understanding of what it means to be an American.

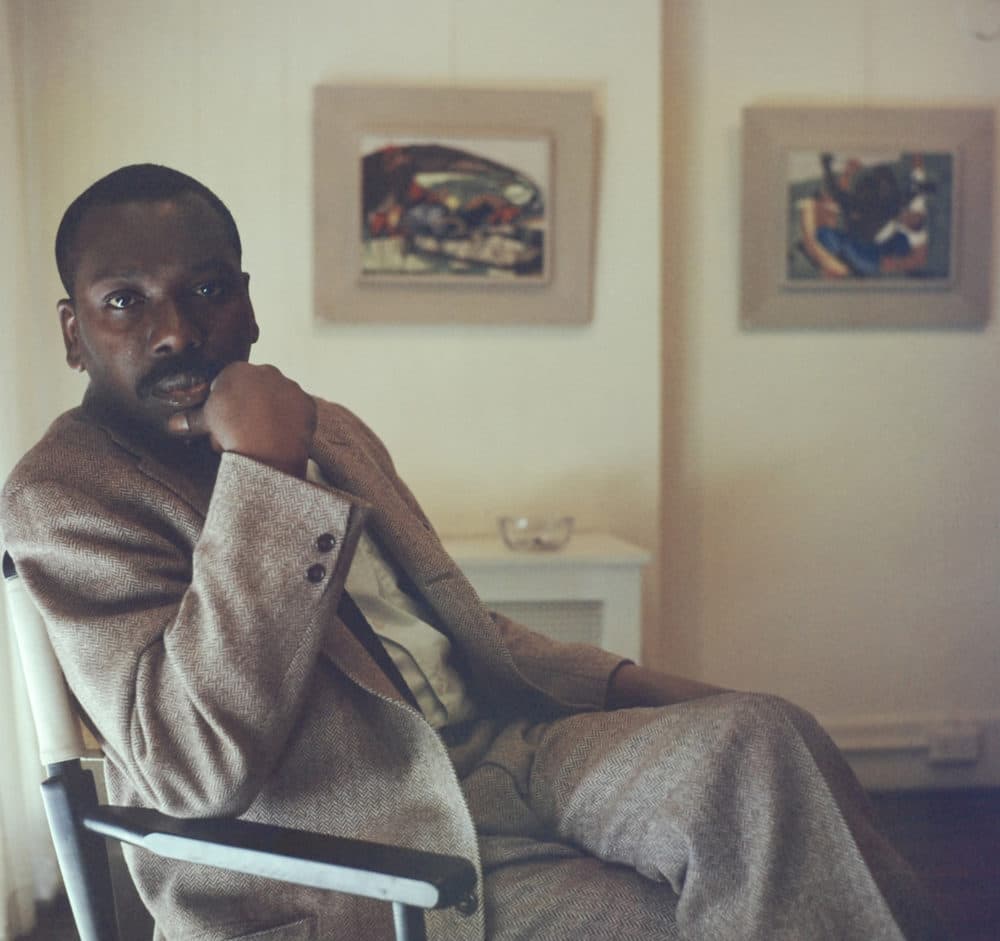

"Jacob’s Ladder," a multimedia installation by Derrick Adams, is an affectionate tribute of Lawrence himself: a worn, empty wingback chair facing a portrait of Lawrence, set atop a carpet of images of black life in America. Placed at the end of the exhibition, the piece is a homely reminder of the human behind the great artist.

"Jacob Lawrence: The American Struggle" is on view at the Peabody Essex Museum until April 26.