Advertisement

Review

Through Letters And Film, Artist Dora García Traverses 'Love With Obstacles'

There’s so much for me to love in artist Dora García’s first solo U.S. exhibition “Love with Obstacles.” Letters and writing take center stage, with author and feminist Alexandra Kollontai as protagonist, throughout the exhibition. Performance, film, drawing and an archival installation coalesce around themes of early 20th-century radicalism, globalism, nationalism, the international women’s movement, and yes, love. These are subjects that to me, have shaped our 21st-century present, and “Love with Obstacles” (at Brandeis University’s Rose Art Museum through May 17) offers an unconstrained, meditative space in which to consider them.

Personally, as a writer and curator, I relish the opportunity to reflect on such subjects, and indeed enjoyed several hours over two Saturdays exploring García’s works. To my mind, the exhibition’s muse, Kollontai, is an under-recognized but fascinating figure of Revolutionary Russian and early feminism. The show is an ascetic yet impassionate assemblage of gestures musing on her thwarted passions.

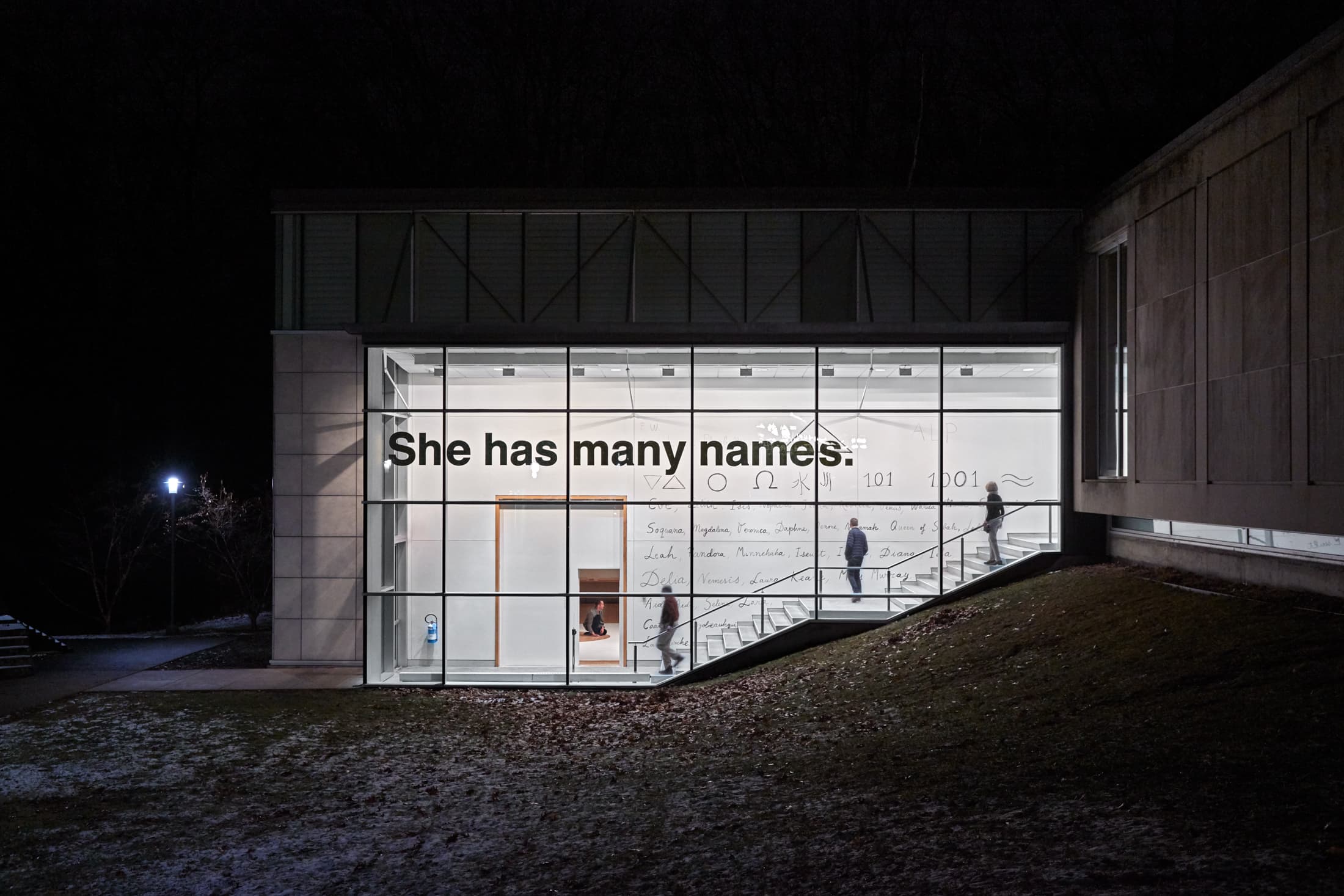

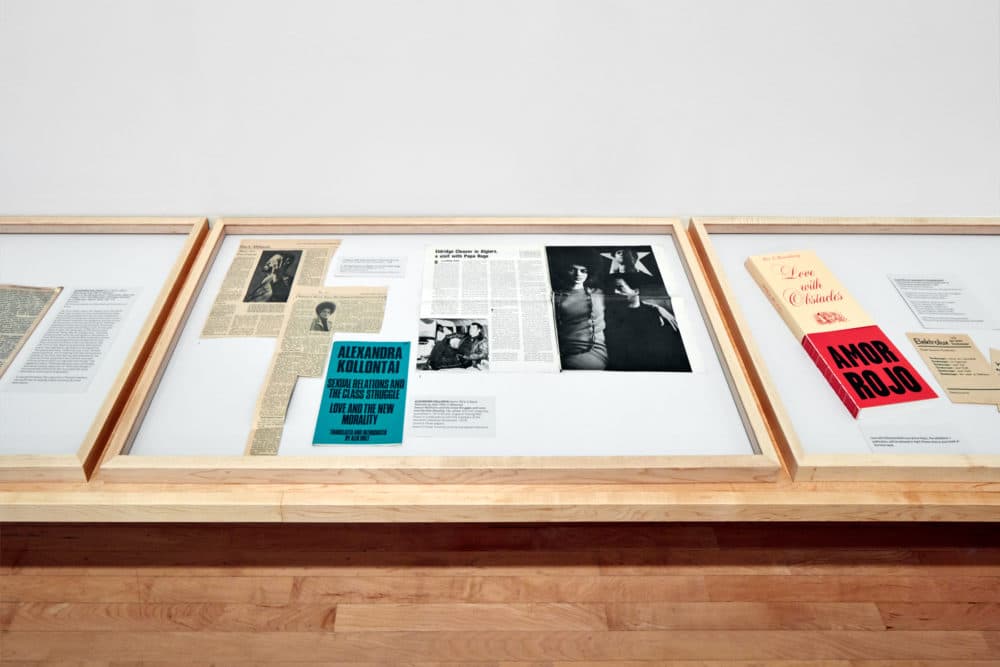

This intricate exhibition’s focal point is its titular film of about an hour in length, exploring the life and letters of Kollontai, a leading but underappreciated figure of global feminism. With the film, García also debuts “The Labyrinth of Female Freedom” (2020), a performance, and “She Has Many Names” (2020), part of a series of aphorisms inscribed in gold leaf on various architectures. These new works are connected via an exhaustive archive comprised of ephemera, books, artworks and manuscripts mined from Brandeis’ Special Collections alongside an additional performance and wall drawings. The exhibition is bound by two aesthetic poles of logos and pathos, that of the institutional and authoritative and that of the individual and idiosyncratic. These polarities encapsulate the main theme of the show: proximity between people and ideas.

Inside a long, semi-enclosed, darkened space, the film plays with the idea of close distance, of emotional proximity despite physical separation. Some of the most powerful scenes are at its opening, as photographic portraits of Kollontai are juxtaposed with her political writings. A Marxist and October revolutionary, she became the first woman to serve in government after she assumed a high post within the Soviet Union. She advocated for women’s rights in that country, and around the world, traveling to speak in support of women’s education and marriage equality. Posters advertising her speeches in multiple languages — now brittle with age and archived with her papers — are flipped through by a woman’s hand as the film progresses. But Kollontai’s full political potential was ultimately obstructed by the machinations of the Soviet government; she was eventually exiled as a diplomat after a break with the Communist Party in 1922. We watch the film from a literal and cultural close distance of several feet, from a marble-like viewing bench at the installation’s entrance, a curatorial move that symbolically approximates the expanse of exile.

On my first visit in late February, a handful of viewers vied for a seat to watch the whole of “Love with Obstacles.” On my second, a week later, I was one of maybe four over two hours. Panic over coronavirus had set in during the intervening days between my visits, introducing phrases like “social distance” to my vocabulary. So maybe low visitation could be chalked up to fear of “close contacts.” But I also wondered on both visits as I sat on the cold, hard viewing bench, who else would love this exhibition? Who is it really for?

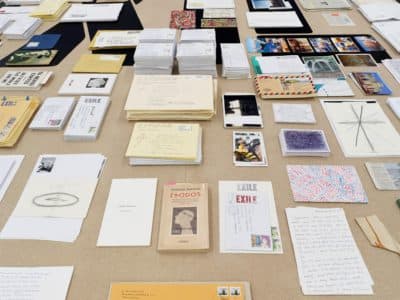

Students and scholars are the short answer: The Rose and Brandeis’ Special Collections, which compose the “Love with Obstacles Archive” (2020), is for teaching and research. So, a rarified audience, one perhaps accustomed to archival vitrines, folios, pencil marginalia and microfiche, used to the demands of careful, slow looking. I’m frustrated that “Love with Obstacles” assumes the institutional format of an archival exhibition, with only a few tacit subversions to the form. Succeeding the “Archive” is “Exile” (2012-present), a sprawling accumulation of letters by a multitude of people writing to museums or galleries (letters to The Rose join collections from previous iterations at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art and other institutions). Viewers are allowed to handle and read these letters, an invitation almost unheard of in a museum or library setting, which creates a tension between the logos of “archive” and the pathos of “exile.” How many viewers appreciate this tension and the illicit feeling one has in being permitted to touch things in a museum?

Advertisement

The letters included in “Archive” and “Exile” alike are embodied feelings — physical remnants of words thought of love, anger and passion — from one inner world to another. I particularly linger over “On Reconciliation” (2018), a selection of correspondence between Hannah Arendt and Martin Heidegger, letters that have captivated the erudite in recent decades. “Between two people, sometimes, how rarely, a world grows…This tiny microworld where you can always escape from the world, and which disintegrates when the other has gone away,” writes Arendt to Heidegger in one from 1970.

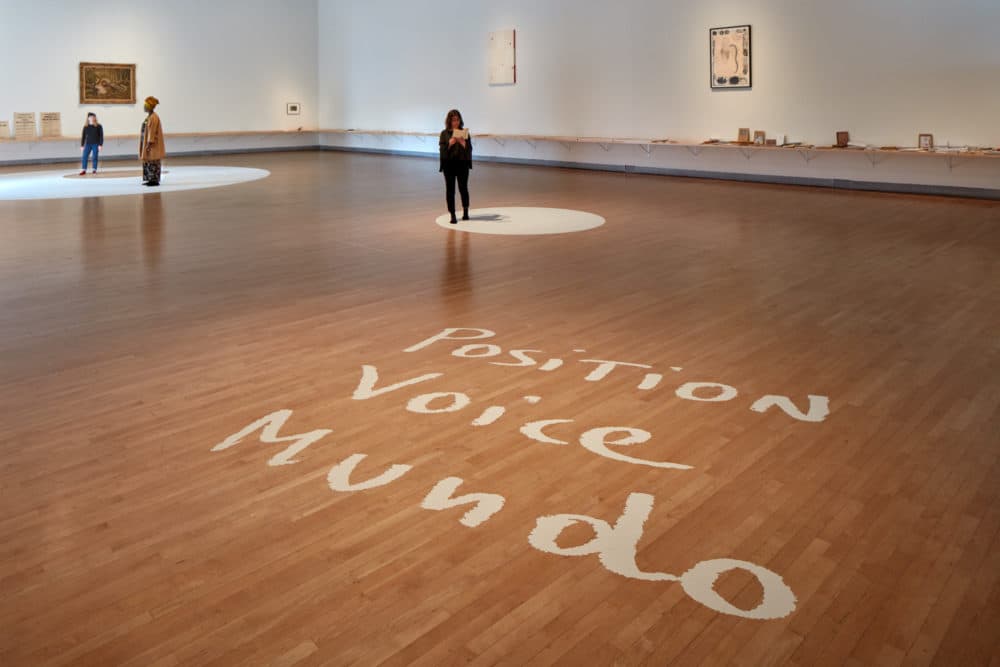

This letter evokes the silent performance of two women in the piece “Two Planets Have Been Colliding for Thousands of Years” (2017), in which over 45-minutes, they maintain an agreed-upon distance and orbit each other inside one of García’s floor drawings. Watching, I feel like an outsider observing two people in the pull of their own impenetrable microworld. Nearby, I can barely hear a third performer as they read poetry inside another floor drawing for García’s new performance “The Labyrinth of Female Freedom.” The performer decides at what volume they read aloud, obscuring or revealing the poems with the audience at their discretion. I get closer to hear but am barred, by all caps text situated on the floor in front of the drawing, from entering the floor drawing myself and getting too close. The poetry and performance, therefore, were still impenetrable to me.

Maybe it’s best that I kept a social distance, however, and didn’t shatter the third wall. The symbolism of the woman sitting cross-legged on the wooden floor, steadfast but unheard, is one that lingers with me as I consider Kollontai (as well as Arendt, Rosario Morales, Rosa Luxemburg, Angela Davis and Gloria Anzaldúa, all referenced in the exhibition). Just as with the performer, I want to hear, more loudly and outside universities, the words and thoughts of these women. Their passions still have resonance and should not know the obstacle of the institution.

“Dora García: Love with Obstacles” is on view at Brandeis University’s Rose Art Museum through May 17.

Leah Triplett Harrington is a writer, curator and editor. She’s the founding editor of The Rib and the assistant curator of Now + There.