Advertisement

As Boston Sits Empty, Street Performers Struggle To Survive

Resume

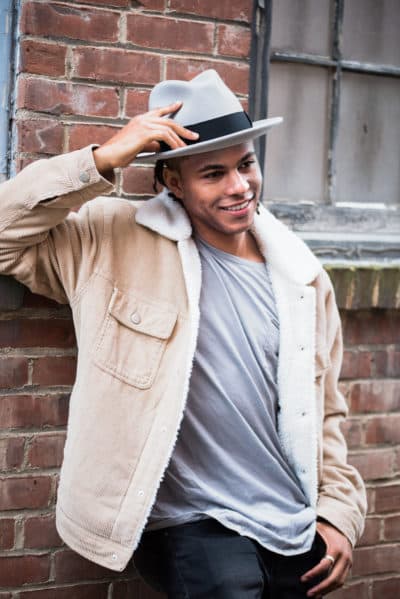

Every summer for the past six years, Cjaiilon Andrade has danced for huge crowds at Boston’s Faneuil Hall.

He calls himself Snap Boogie, and he can make his body do impossible things. He ripples, lurches, flings himself in somersaults through the air. He glides across the pavement like it’s glass.

"It's magic, basically," says the 28-year-old dancer from Boston. "It looks like I’m flying on the floor."

The crowd adores him. He’ll pick an unsuspecting onlooker and make them dance, and they let him, because he’s charming. Afterward, he’ll shake their hand and lead the crowd in a cheer.

At least, he used to. In March, as the coronavirus spread across New England, the crowds began to thin. At first, Snap Boogie tried to soldier on. But he couldn’t do his act if the audience wouldn’t stand close together, if he couldn’t shake someone’s hand and make the crowd applaud.

"It just kinda took my heart away," he says. "You know? It’s literally everything for me. I love performing. I love — I love everything about it."

Faneuil Hall paused its street performer program in March. The summer season accounted for about half of Snap Boogie’s annual income, and his winter gigs performing at halftime shows have dried up, too. COVID-19 has put Snap Boogie, like so many street performers, out of a job.

Before the pandemic, Boston was one of the country’s busking hotspots. Performers from around the world flocked to the city to audition for a coveted slot at Faneuil Hall, where they could pull in tens of thousands of dollars in a single summer. Most of the city is fair game — no permit needed. In 2019 Cambridge waived its permit fee in order to attract more performers to its streets.

Now, Boston’s public spaces are dormant. And that has pushed some performers precariously close to the brink — particularly those who already lived on the margins.

Like Philip Bloom, aka Rami Salami, a balloon-twisting clown who has been performing in Boston since the mid-'90s. He lives simply, traveling abroad in the winter and clocking long days in Faneuil Hall in the summer, sleeping in his converted Honda Element to cut down on the commute.

"My car was a lifeboat," Bloom says. "I knew that wherever I went, if things went sour, I could get a flight back home, get into my car with all of my equipment there and be able to go out and make money and work." He pauses. "Except for this year."

Bloom was in Israel when the country went into lockdown. He caught a flight home and crashed with a friend for a few months. After that, he lived in the Honda full-time, driving around to parks, camping, trying to spend as little money as possible. And then he got into an accident.

"When my car got hit, suddenly I didn't have a place to stay," Bloom says. "I didn't know what I was going to do. I didn't have the money to repair it, so I could keep it as a home."

It was a low moment. Desperate, Bloom posted a plea to Facebook — and before long, an acquaintance offered to put him up in one of his properties, a recently-shuttered massage parlor in central Massachusetts.

But Bloom is still not sure when he’ll be able to get back to street performing. He’s 63 years old — it’s just not safe.

"The kids spread it," he says. "Every kid came in close for a picture and a hug. All of them. You know, I was eight inches from [them], nose-to-nose together with the big smile. And that's not going to happen again."

Bloom says he’s lucky — he has a place to stay and is on a list for subsidized senior housing. The friend who is putting him up runs a charity for pediatric cancer patients, and Bloom is developing a physically-distanced clowning show for the kids.

Snap Boogie is pivoting, too, trying to build an audience online. For now, they’re both finding ways to adapt. But Boston’s streets are unlikely to see them anytime soon.

This segment aired on September 4, 2020.