Advertisement

Basquiat And The Hip-Hop Generation On View At MFA

In the early 1980s, New York was a city just barely holding on. Manufacturing jobs had abandoned the megalopolis, and without a tax base, the city had been forced to lay off workers and cut basic services like trash pickup. Unemployment soared, along with crime. Middle-class whites fled for the suburbs, leaving behind neighborhoods that were distinctly poorer and darker than before.

But amid a toxic blend of crumbling infrastructure, burnt-out buildings and open-air drug marts, a creative fermentation percolated that would brew a global revolution in art, music and design.

“Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation,” opening at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston on Oct. 18, takes us back to the moment when graffiti-splattered subway cars snaked around a decaying city, ushering in an electrifying shift in painting, drawing, video, music, poetry and fashion. In the space of just a few years, scrawls on the sides of buildings leapt onto elite gallery walls, not just in New York, but in Italy, Germany and the Netherlands. Suddenly, clothing combinations common only on the D train were strutting down New York and Parisian runways. Rapping, DJing, sampling and scratching, once heard only at South Bronx block parties, suddenly topped the Billboard charts. It was a mélange that would come to be labeled “hip-hop,” a term coined to describe a youth culture originating with Black and Latinx kids who rhymed, breakdanced and “bombed” their way into art world visibility.

“It was all speaking to one another,” says writer and musician Greg Tate, co-curator of “Writing the Future” with Liz Munsell, curator of contemporary art at the MFA. “They are extrapolating on a common language that they've developed in their own laboratories, down there in the train yards and the subterranean corridors of the city at 3 or 4 o'clock in the morning, working feverishly to get these pieces up so that whole city will see them when the trains roll out for rush hour.”

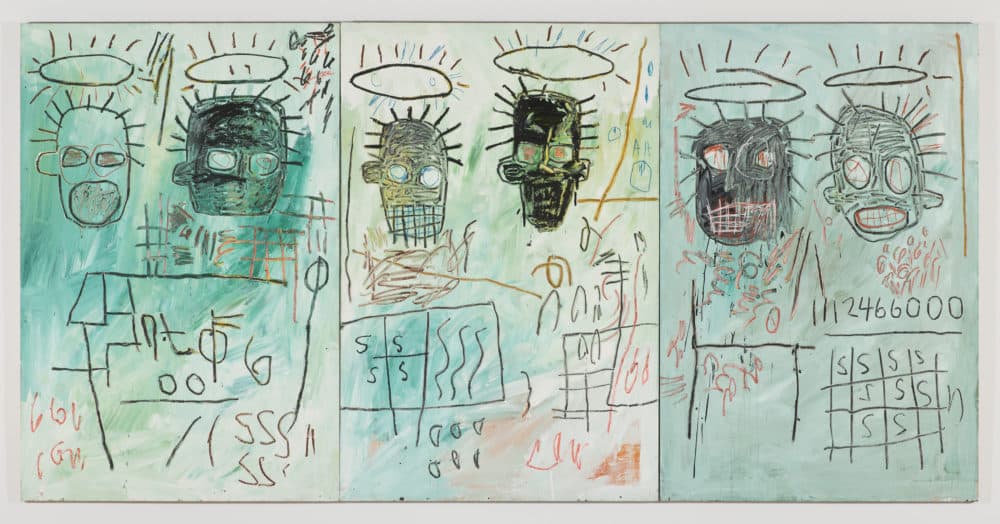

Jean-Michel Basquiat, or “SAMO” in his graffiti tags, is perhaps the best known “post-graffiti” street artist, often attached to his friend and collaborator Andy Warhol. But as the exhibit makes clear, Basquiat was not a lone street savant shouldering his way into a rarified art world, but just one artist in an entire movement of Black and brown multidisciplinary artists — some with art school training, some without — who rapped, rhymed, bombed and tagged their way into the dominant collective consciousness in the 1980s. With swagger and determination, they trampled barriers erected by the traditional cultural gatekeepers.

And so, the exhibit displays not only pieces by Basquiat but works by A-One (Anthony Clark), Futura (Lenny McGurr), Lady Pink (Sandra Fabara), Kool Koor (Charles Hargrove), Fab 5 Freddy (Fred Brathwaite), Lee Quiñones, ERO (Dominique Philbert), Keith Haring, LA2 (Angel Ortiz), Rammellzee and Toxic (Torrick Ablack).

Advertisement

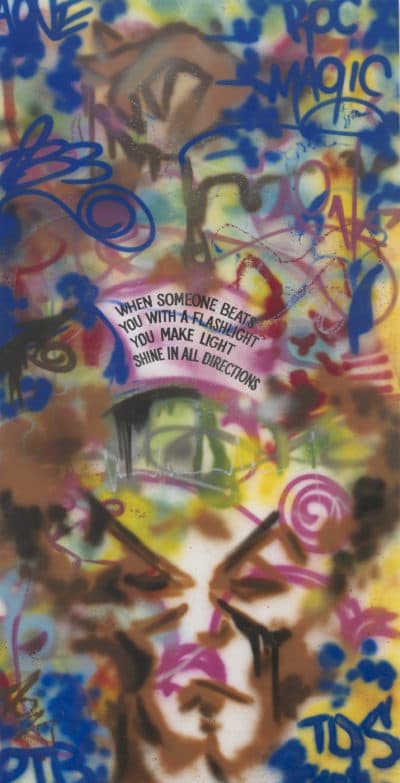

“Stylistically speaking and thematically speaking, they all shared a mutual interest in language and incorporating language into their works,” says Munsell. “Not just in language as a focal point, but in language as kind of a material that could be abstracted, transformed into something that was really all their own.”

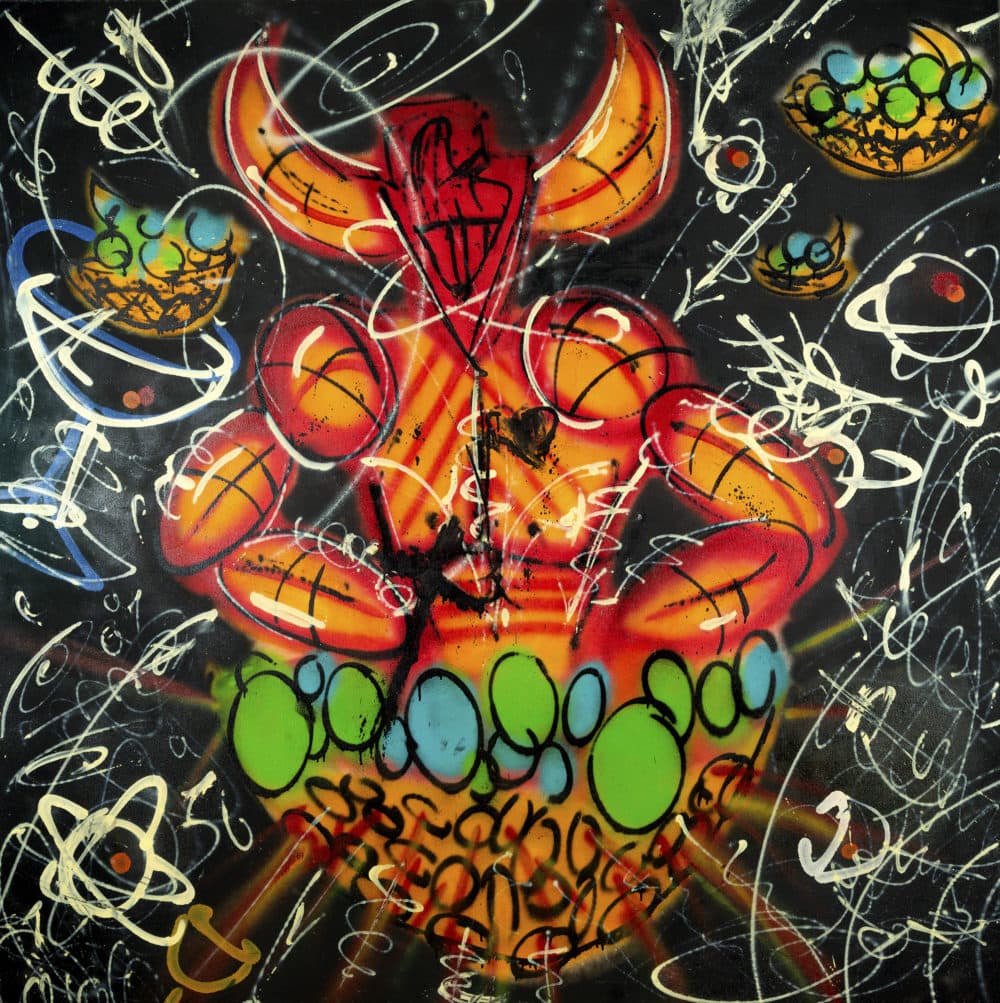

Rammellzee, a half Black, half Italian native of Queens, traveled down the path of “Gothic Futurism,” documenting a mythical battle involving letters weaponized to reclaim the language from a dominant culture exerting social control. He was also a rapper whose music would influence hip-hop artists like The Beastie Boys and Cypress Hill.

Futura pioneered expansive fields of color overlaid with abstraction (from time to time he also rapped and spray-painted backdrops for The Clash) while Kool Koor created futuristic utopian scenes. Lady Pink painted powerful women presiding over a corroded city in a comic book style, while A-One worked in a style of emphatically ornate lettering he called “aerosol expressionism.”

Coming from New York’s outer boroughs — Queens, the South Bronx and Brooklyn — this group brought a clamorous authenticity to the art scene with vividly in-your-face works incorporating intricate wildstyle lettering and technicolored compositions. Their work was large and loud, critiquing social ills and celebrating aspects of pop culture and life on the streets.

“You couldn't avoid seeing the work on the train if you took the trains in New York,” says Tate. “It was clear that a lot of these kids had a lot of talent and were really making bold, audacious visual statements with the city as their exhibition space.”

While they found their inspiration in underground comic books, movies, street signs and urban iconography, they didn’t shy away from a subversive exploration of racial discrimination, criminal justice, and even artworld prejudice and snobbery. Basquiat’s “Hollywood Africans” took on stereotypes perpetuated of Blacks in Hollywood, while A-One’s “Flashlight Text Survival,” created in collaboration with Jenny Holzer, alludes to persistence in the face of police brutality.

“They're making pithy statements about society and very much aware of themselves as being at war with very mainstream, very white institutional ideas of what art and art-making is,” says Tate. “They’re rebels, artistic radicals, who decided the city is going to be their atelier, their studio, their canvas.”

“Writing the Future” sets the stage in the foyer with a large projection from the 1983 hip-hop documentary “Style Wars.” We see Fab 5 Freddy’s bombed subway train with images of a row of Campbell’s soup cans, painted with assistance from Quiñones, referencing Warhol’s “Campbell’s Soup Cans” series. From there, we witness a shift as a common symbol of urban blight gets transformed into the essence of artistic cool. Suddenly, the work of Basquiat and colleagues like Quiñones and Futura move into edgy galleries, like the Fun Gallery, one of the first to dedicate entire solo shows to graffiti artists. On display is “Fun Fridge” of 1982, a refrigerator that once inhabited the East Village gallery. The piece is now a sacred touchstone of sorts — it’s been tagged by nearly every artist in the show.

We see not only the “writing” of these artists on canvas and two-dimensional supports, but on clothing and objects, like a neon pink Stephen Sprouse suit tagged by Keith Haring and LA2 and worn by Madonna on stage, or a Sony boombox sprayed by Futura. There is a gallery dedicated to the music they created and that inspired them. (A soundtrack is available on the MFA’s website and Spotify.) Other galleries at the museum explore Basquiat’s portraits of his friends, his exploration of anatomy in his work, along with Lady Pink, and finally, how these artists incorporated otherworldly notions of shamanism, science fiction and spiritualism into their pieces. Rammellzee’s “GASH-O-LEAR” bodysuit, fashioned out of found items and used in some of his performances on stage, resembles the elaborate robe of an African shaman by way of Parliament’s George Clinton. In all, there are more than 120 pieces in the show that spreads out over several galleries.

“They definitely kind of shook all of it up in the same way that punk and hip-hop shook everything up,” says Tate. “It was a youth brigade going across disciplines, changing everybody's idea of what music could be, what art could be, what dance could be.”

They brought fight-the-power flare to an art scene stalled in white box pretension, flaunting convention (and the law) to be seen and heard on their own terms, amid the detritus of a deteriorating world. In that way, they may have something to say to today’s young creators.

“For younger people, Picasso is not their grandmaster, Pollock is not their grandmaster,” says Tate. “A lot of the work that has represented modernism in the galleries and the museums is just not speaking to them. But this work is very much speaking to an aesthetic that is very familiar because of popular music, because of the internet. Rammellzee and Fab 5 Freddy and Jean-Michel Basquiat are the cultural thought leaders of their time. They are stars still because they accomplished things that are still recognized and accessible to folks.”

“Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation” is on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston through May 16, 2021.