Advertisement

Authentic Salem Witch Trials Artifacts Are On Display Amid Halloween Kitsch

The season of the witch peaks in October, especially in Salem. But this year — amid drastically restricted Halloween activities — the real reason Salem is known as the Witch City is on display at the Peabody Essex Museum.

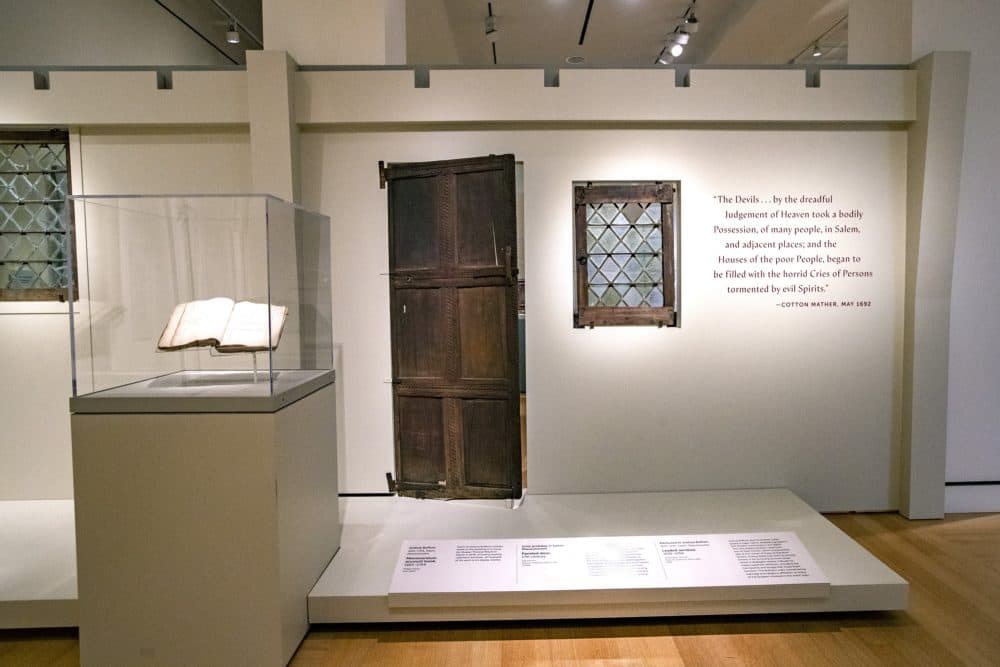

PEM's Phillip's Library holds the largest collection of Salem witch trials materials in the world, including some 550 documents on deposit from the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. Now, 47 rare pieces from this chapter of colonial history are being shown for the first time in 30 years.

The fact that they're in a gallery just paces away from shops where tourists can buy Witch City hoodies and pointy black hats isn't lost on Dan Lipcan.

“That witch kitsch stuff can't exist without this stuff, and vice versa,” the head of the Phillips Library said on a recent afternoon, “so it's on us – because we have the original material, because we have the objects and the possessions of the people involved – we felt like it was our responsibility to tell their stories and talk about what the issues really were.”

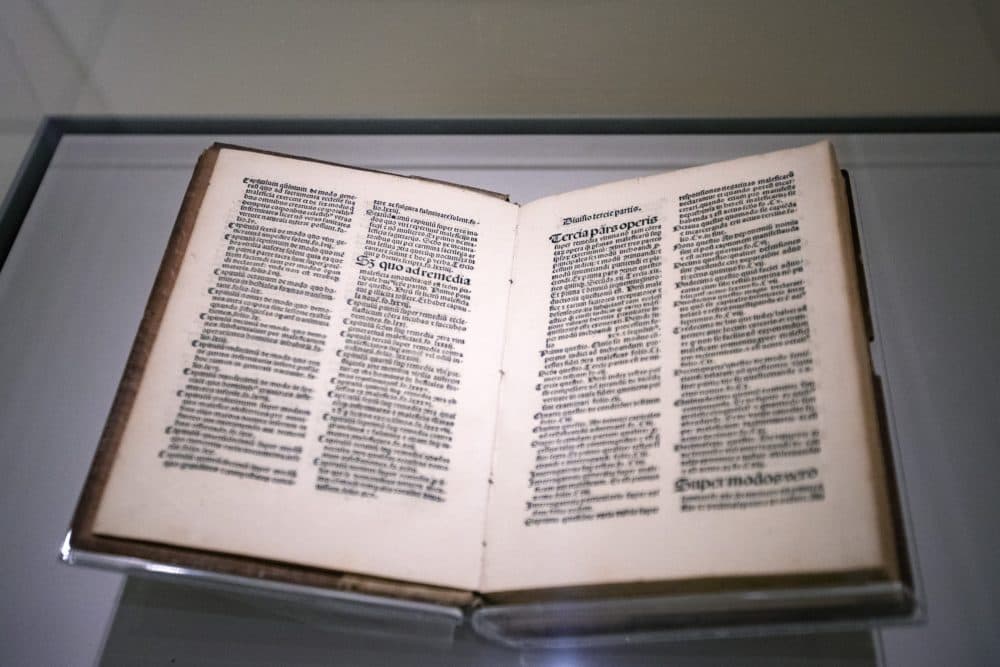

But as we enter the new witch trials exhibition the first glass-encased object we encounter isn't actually from Salem – it's a 1494 edition of a European tome called the Malleus Maleficarum.

“The translation of that is 'The Hammer of Witches,'” Lipcan explained, “and that was written by Heinrich Institoris, who was a very aggressive inquisitor active in the Holy Roman Empire or Germany.”

The Malleus, as it's sometimes called, is the original manual on how to hunt people colluding against God with the Devil. It's estimated more than 40,000 victims – mostly women, many of them midwives – were tortured and executed for practicing witchcraft across Europe over about three centuries.

“And so we're establishing this context for the Salem witch trials to show where these ideas came from,” Lipcan said.

"This is really Salem's story. Whether Salem wants it to be or not, it is the Witch City.”

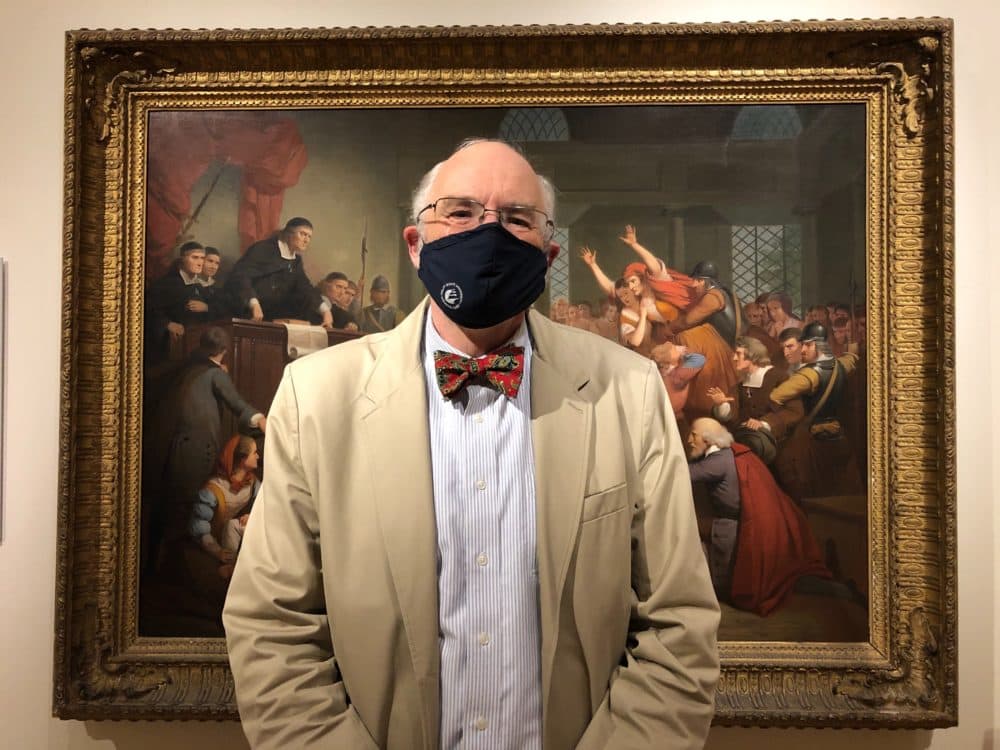

Emerson Baker

A lot of us know about the wave of hysteria that swept through the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the 1690s that would ultimately kill 25 innocents. Maybe we learned about the horrors in school, or through books and movies like the adaptation of Arthur Miller's “The Crucible.” But Lipcan said there are plenty of misperceptions about what really happened. He hopes the exhibition makes it clear that there are no historical connections between the Salem witch trials and Halloween.

PEM unfolds the complex narrative by pairing objects with artworks, surviving architectural elements, influential books and original documents from 300 years ago. To get history right the curatorial team tapped Salem State University professor Emerson “Tad” Baker.

“This is really Salem's story,” Baker said when he entered the gallery for the first time. “Whether Salem wants it to be or not, it is the Witch City.”

The historian was giddy to finally see artifacts with his own eyes that he'd only read about in books. “It's just an incredibly exciting moment,” Baker said, "and I'm just thrilled that the museum is has undertaken this really important project.”

Baker wrote the book, “A Storm of Witchcraft,” and went on to describe how the government failed to protect its falsely-accused citizens in 1692. He said the deadly injustices still cast a long shadow over Salem. Baker is optimistic the new exhibition will help visitors understand the environment that fomented months of chaos by illuminating the Puritans' lives and struggles.

Advertisement

Lipcan pointed out that some of the challenges they faced might sound familiar to us today. “There was extreme weather in New England. There had been a smallpox epidemic. There was a war to the north with the indigenous populations and the French and there were refugees coming down from the border territories in New Hampshire and Maine,” he said.

The Puritans' crops failed because of killer frosts and dry summers, which led to starvation. They were nervous about a new governor and a decline in spirituality. They squabbled over land. Baker said rampant uncertainty and fear pushed them to search for something – or someone – to blame.

“Under those conditions, that's when people say 'That's it! My husband has taken ill mysteriously...the cow has stopped producing milk...lightning struck our barn and burned it down,'” Baker said, “'and Bridget Bishop looked at me the wrong way last week or she cursed me when I wouldn't give her milk because she was hungry.'”

Bridget Bishop was the first person to be hanged for witchcraft in Salem. Her death warrant — the only one in PEM's collection — is in the gallery, along with testimonies and records of humiliating physical examinations the accused endured.

Baker said the Puritans weren't merely superstitious; for them evil was omnipresent and witches were real. “'They're here to destroy us and our society – they want to wipe out our families, our government, our church, everything we believe in,'” he said channeling their beliefs, "'and how do we stop them when we don't even know who they are?'”

In the gallery there's a chilling 1853 painting by Tompkins Harrison Matteson titled “Examination of a Witch.” A portrait of Judge Samuel Sewall who eventually apologized for his involvement in the trials hangs on another wall. There's also a sundial owned by John Proctor and a set of George Jacobs' canes. Both men were hanged for witchcraft on August 19, 1692.

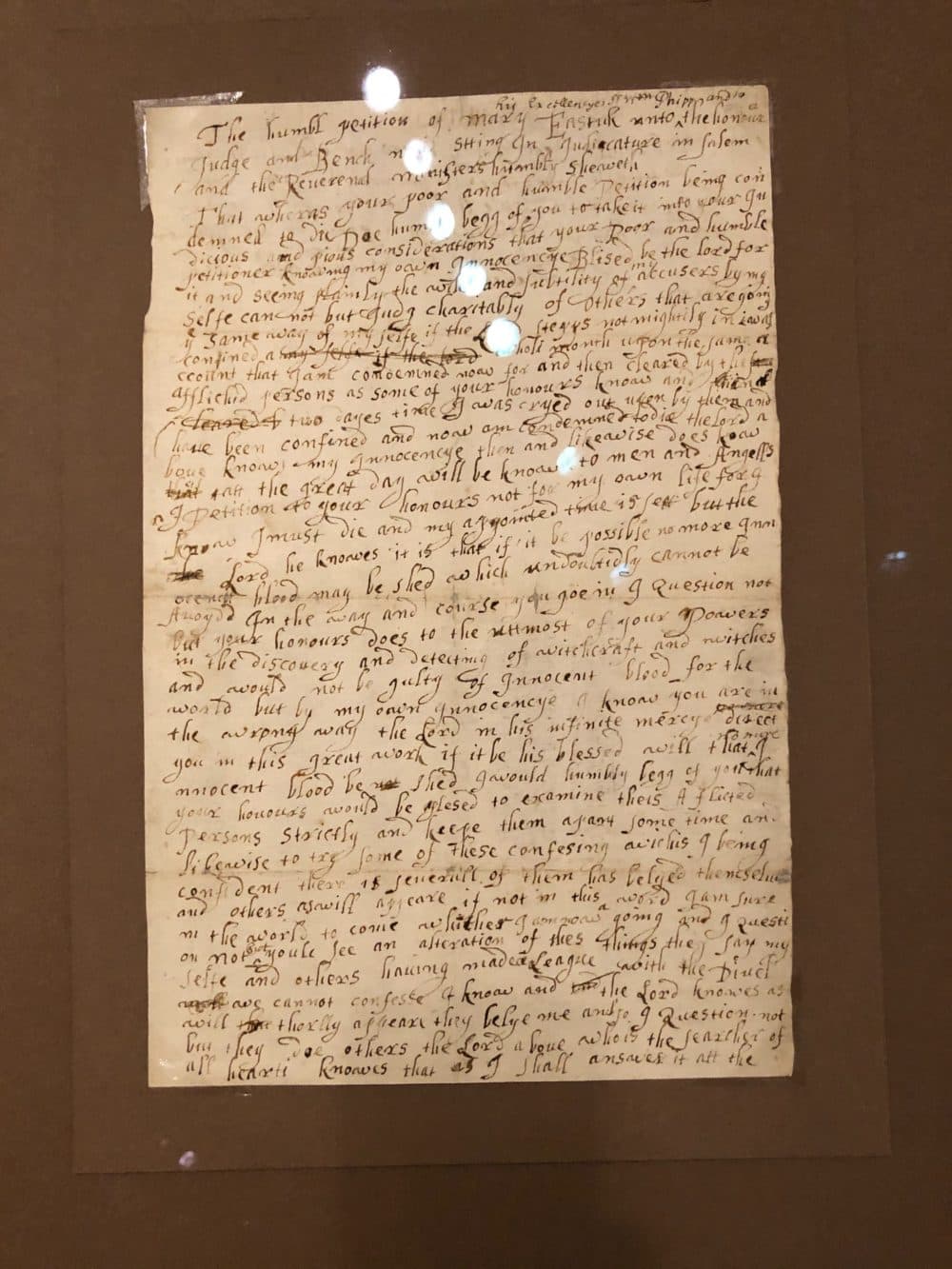

Baker, who's also an archaeologist, made a beeline to a small valuables cabinet that belonged to Joseph and Bathsheba Pope. She was a notorious accuser. A petition is displayed steps away, under glass, its preserved page covered in uneven, inky sentences. They were penned by Mary Easty, one of Salem's accused.

For Lipcan, Easty’s handwritten words to the magistrates are the most moving in the universe of witch trials documents. “I get goosebumps thinking about what she must have been going through,” he said. He recited a quote from her plea that's featured on the gallery wall.

“I petition to your honors not for my own life, for I know I must die and my appointed time is set. But if it be possible, no more innocent blood may be shed.”

Baker feels this petition strikes at the injustice of what happened in 1692 and shows how the witch hunt decimated families, including Easty's.

“She'd already lost her sister, Rebecca Nurse. She had another sister who was in prison, Sarah Cloyce, who survived. But terrible loss just in that one family, right?”

As visitor Vilma Cosme of Chicopee walked out of the exhibition she said it reminds her of innocent people today who've been wrongfully killed.

“Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, a lot of unfortunate things in the world and what we're living through now,” she said. “It's just kind of like history repeating itself.”

That's why Dan Lipcan said the exhibition's final section titled “Reckoning and Reflection” highlights what Salem has done – and continues to do – to raise awareness about the real legacy and tragic reality of the witch trials.

“Because all of these things are present today,” he explained, “and they will continue to be until as a society we're able to put a stop to it and to speak up.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story misspelled Breonna Taylor's name. We regret the error.

This segment aired on October 26, 2020.