Advertisement

Boston Camerata Revisits Purcell's 'Dido And Aeneas' — An Opera For Distanced Lovers

Composed for a girl’s boarding school in 1689 (or possibly 1687), “Dido and Aeneas,” Henry Purcell’s only true three-act opera, is one of the great masterpieces of English music — unceasingly inspired and, sometimes literally, bewitching. Its popularity has never diminished. Three hundred years later, Mark Morris not only choreographed it, he also danced both of the leading roles, Queen Dido of Carthage and the Sorceress who is out to destroy her. In its first Boston performance, the now legendary mezzo-soprano Lorraine Hunt (not yet Lieberson) sang Dido, and her noble yet heart-rending performance of the queen’s tragic aria, “When I Am Laid in Earth,” is one of my most precious musical memories.

Although Purcell’s music has become over the years the domain of early music performers, such great operatic divas as Norwegian Wagnerian soprano Kirsten Flagstad, Janet Baker, Victoria de los Ángeles, Tatiana Troyanos and Jessye Norman have made memorable Didos. Just as productions have taken many different tacks, from the historically informed to the bizarre. In 2005, Boston’s Handel and Haydn Society did it in an onstage wading pool (neither the first — nor the last — opera to be performed in a pool of water).

But the crown for the most historically significant American performance — the first modern performance to use period instruments, the right number of instruments, consistent tempos and correct pitch — belongs on the head of the Boston Camerata’s founding director, Joel Cohen. And now, 40 years later, under the direction of the Camerata’s current artistic director, Anne Azéma (who happens to be married to Cohen), the Camerata will be revisiting its former triumph in its first “digital” production, with the title “Dido and Aeneas: An Opera for Distanced Lovers.”

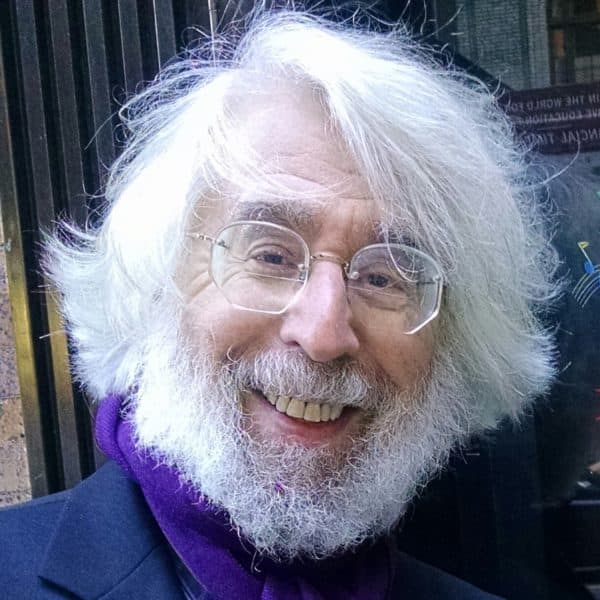

I spoke to one of Boston’s treasures, MIT Music Professor Emeritus Ellen T. Harris, internationally admired expert on Baroque music, especially Handel and Purcell. In 2018, she rewrote her landmark 1988 study, “Henry Purcell’s ‘Dido and Aeneas’” (Oxford University Press), with tons of new information. She appears in brief vignettes on the Boston Camerata website and will also do a half-hour preperformance talk. What, I asked her, made “Dido” so special?

Her first answer was that for a full opera it’s really short — less than an hour. “Things move along very quickly. There’s no backstory. You’re thrust immediately into the action. You become a character. Even when Aeneas enters, there’s no wooing, no love duet — nothing you would expect in a love story. You have to understand that Dido has simply accepted Aeneas’s suit.” Unlike the episode in Virgil’s “Aeneid,” the original source of the story, there’s no conflict between love and duty. Here, the real conflict is between Dido and an evil Sorceress (though in this version, as in some earlier versions, the role is labeled “Sorcerer” and sung by a man). “The Sorceress hates Dido and, determined to ruin her, brings witches into the plan. No gods and goddesses tricking the lovers into their relationship. They’ve had their one night — which is also different from the ‘Aeneid,’ where their relationship goes on for months. This is a one-night stand. Aeneas says he’ll stay, but Dido sends him out and then she dies. It works beautifully for a girls’ school — a good lesson for 17th-century aristocratic young women: a one-night stand leads to death — social death.”

Harris defends the libretto by Nahum Tate (the 18th-century poet notorious for giving “King Lear” a happy ending), which she acknowledges has come in for much abuse. I always felt Purcell’s music rescued the banality of Tate’s words in the lovers’ parting duet (“Away, away!” “No, no, I’ll stay”). “But it’s wonderful,” Harris insists, “though not as wonderful as the music.” One of the things she likes best is that “you don’t know at the end what has actually caused Dido’s death. Is she affected by Aeneas’s charm? Valor and charm! The witches and the Sorceress also have charms. Which ‘charm’ is doing more damage?” Dido’s sister, the “endlessly, knowingly perky Belinda,” predicts that Cupid “will strew the lovers’ path with flowers. At the end of the opera, Cupid is scattering roses on Dido’s tomb. I love the way Tate slips these things into the libretto.”

You can hear Harris for yourself speaking about Purcell’s fascinating key changes, the connection between Tate’s “wayward” witches and Shakespeare’s “weird sisters” in “Macbeth,” and the gender ambiguity of the Sorceress:

I also spoke with the Camerata’s artistic director Anne Azéma, who seemed more excited than daunted by the challenge of putting on a production during the pandemic.

The Camerata had, of course, planned for 2020-21 before COVID-19. “It was going to be called the ‘She Too’ season — the ideal season to return to ‘Dido.’ I’ve directed 20 new programs since I became director — but time to time it’s important to return to what made Camerata Camerata. And that ‘Dido’ 40 years ago marked a turning point in the performance practice of 17th-century music and for Camerata. It was a landmark!”

With their tours canceled, what were they going to do?

“I’ve become more and more interested in staged productions,” Azéma told me, “I knew I needed to look at this. In a tragic way, COVID-19 was handing us something we needed to do. We read the libretto, and started dreaming and hoping... What’s fantastic about ‘Dido and Aeneas’ is its portrait of the psyche of a woman who is quite complicated. Seventeenth-century music is so beautiful, so varied. In the little vignettes you have that make this opera — each of these vignettes has a world of passion, of tragedy, of reflection of how to deal with something you do not expect.”

Azéma is also interested in the political situation in “Dido.” “Dido is troubled. We spend the opera discovering what it is. She’s fallen in love but she’s not completely open to that relationship. She’s a widow who faces temptation, a tentative way to embrace life. A grain of sand gets in the wheels. And that man is not fully committed to her. The ‘machinery’ is against them. She’s from Lebanon — Tyre. Her brother kills her husband. She flees disaster, like Aeneas leaving Troy. Like Aeneas, she’s a political entity. She rebuilds a city and it’s going well. She’s sought after. Then this is the card that’s being played. The music is the passionate essence of these turmoils.” Purcell’s music, she says, is “so fresh — he died when he was 36! He gives us an incredible collection of colors. Two arias with ground bass. Creative images in the music — a storm, lightness of being, an otherworldly sorcerer.”

The “orchestra” will be a string quartet and harpsichord, with some of Boston’s best early-music players, including stellar cellist Phoebe Carrai and harpsichordist John McKean (chair of the Longy School’s historical performance department), as the rhythmically indispensable continuo players. Dido will be sung by Sri Lankan mezzo-soprano Tahanee Aluwihare, who is now based in Boston. The chorus and smaller rolls are drawn from students at the Longy School.

The original score, Azéma says, “is a mess. There’s nothing from Purcell’s hand. So much is left to our own choices. We’ve got fabulous players. I don’t want a period piece in period costumes, but I want the basic grammar and language to be what we imagine the 17th-century norm to be. There are various manuscripts and sources for the libretto. Some manuscripts indicate a lower clef for the Sorceress. The Second Woman is described differently in various sources. We follow a highly reputable edition from the mid-1990s.”

“You can’t really have a live performance without taking large risks,” Azéma insists. This won’t be a “public” performance in the usual sense. The cast will be together in a large room (production photos show them wearing masks), with a remote choir taped separately, and silent film, with outdoor scenes. The separate elements will be edited together. “There are so many ‘Dido’s out there, and happily so. I can’t disclose everything, but it will be a technical feast — an exploration and an adventure.”

The Boston Camerata’s virtual performance of “Dido and Aeneas” will be available from Nov. 14-29.