Hip-Hop Broke $ean Wire's Heart, And Healed It

$ean Wire works best in the morning. He likes to write in the studio, just him and the engineer, a beat playing on a loop as he feels his way toward a verse. Other times, he writes from his bed. He likes to have morning sun shining through the window, and a nice scent in the room. “My senses all have to be in tune,” he says.

Wire is an artist at once tormented by and in love with the act of self-expression. “Music was always the medicine to what I was feeling,” the Boston rapper says, before remarking, a mere moment later: “Music broke my heart so much.” He is a perfectionist who strives to live in the moment, a professional who resists his own ambition. “I used to think that music was my only purpose on Earth,” he says. “Music isn't my only purpose on Earth.”

It is a day after his 25th birthday, in a Zoom interview, when Wire makes this declaration. It’s also almost exactly a year since he dropped his debut studio album, “Internal Dialect,” in January 2020. Last February, he performed for a real-life audience in Cambridge to promote the album. As he sang, the crowd raised its hands and swayed along, a sea of club-issued paper bracelets glowing orange under blue-tinted lights.

The show was supposed to launch a tour for “Internal Dialect.” Instead, it turned out to be the pinnacle of an abortive album rollout that was cut short when the pandemic sent the country into lockdown in March.

“I’m not even gonna lie — at first I was kind of like, ‘Damn, every time I’m, like, 10 steps ahead, God puts me 20 steps back’,” Wire says. Now he sees the hiatus as a blessing. “I wasn’t ready, you know. So in due time, divine time, it’s gonna happen.”

“Internal Dialect” nevertheless emerged as one of the strongest projects to come out of Boston last year, a luxuriant sonic exploration of struggle and self-seeking, animated by Wire’s searching vulnerability. It is a hip-hop album rooted in melody — Wire sings more than he raps, and even when he raps, it almost sounds like he’s singing. His voice functions as a kind of backup chorus, a throng of crooning falsettos that cradle introspective verses. On "Internal Dialect," he sings about falling in love and falling out, of professional ambition and professional disenchantment, of feeling low and feeling better.

“Internal Dialect" is a continuation of his 2019 EP “Dear,” Wire explains. But where “Internal Dialect” offers a warm openness, “Dear” is raw, a step closer to pain. The EP — which helped earn Wire R&B Artist of the Year at the 2019 Boston Music Awards — was written during a period of depression, he says. Mental health is something he still struggles with. “Those days where --” he pauses. “S---, I’ll be in bed, you feel me? … It would feel like I'm not even here in the physical. I feel like I can't even feel my hands. I can't taste.”

Wire grew up in Dorchester and went to the Madison Park Technical Vocational High School in Roxbury. Both his parents worked, so he spent a lot of time in Waltham with his grandmother, a devout Christian from Alabama who made him go to church. The only thing he liked about it was the music. “Everyone in that church came there from the South, so the music was very soulful,” he says. “[It] definitely struck something in my head.”

Advertisement

His parents loved music, too. For his mom it was American hip-hop and pop: Lauryn Hill, the Beastie Boys, Tina Turner. For his dad, it was Jamaican reggae and dancehall: Shabba Ranks, Super Cat, Red Rat. But it was Najee Janey, Wire’s cousin (technically, his aunt's husband's nephew), who got him into rapping. Wire remembers making up his earliest raps with his sister at home; then it was freestyling at the lunch table, and later, recording in GarageBand.

With Janey, Wire formed a hip-hop collective called Most High Kingdom. Membership has shifted over the years, but its core members are Wire, GIB DJ, CuRRell, Janey and Milkshaw Benedict, another cousin. (Janey and Benedict are both nephews of Kim Janey, the Boston city council president and soon-to-be acting mayor.) The members of Most High Kingdom share collaborators, appear on each others’ projects, and occasionally record as an act. Janey and Benedict opened for Wire at his album release show last year. “It’s a brotherhood,” Wire says.

The rapper's closest collaborator is probably Gibson Alcott, a.k.a. GIB DJ, a producer from Allston whose woozy, distorted beats form the foundation for both “Dear” and “Internal Dialect.” The producer likes to mix Wire’s voice in layers, lending his songs an intimate, enveloping quality. “Gibson inspired me so much to get all the way uncomfortable with music,” Wire says. “He doesn’t stay stagnant. He never likes to create one thing, which is inspiring to me, because I never like to do one thing, you feel me? I'm always trying to do something challenging, you know, something that people are going to look at me like, ‘What the f---? What is he doing?’”

In 2020, Wire remained true to his intent to never stay stagnant, releasing a steady string of singles. He sounds loose, focused, as in command of his lyrical facilities as his melodic instincts. On “Intertwine,” he lays candid rhymes over a languid guitar sample that sounds like it was recorded underwater. His verses gather speed, culminating in a rebuke of the music industry’s corrupting demands: “Not about the music/ Not about how many hours that you put in/ Only about who you know and all the favors that you doin’/ You won’t get it back,” he raps, syllables striking like syncopated bullets. “Thinking that I gotta sell my soul/ To just get on track.”

Wire gives the impression of a man pulled in two directions: on the one hand, there are the pressures of the industry, the drive to succeed; on the other, his desire to follow his artistic instincts and work at his own tempo. “It's like you're battling with yourself,” he says. “So much of it stems from you wanting to be great. Every artist want to be great. … We want to live off that s---, you know?”

These days, he seeks balance. He gets up early, tries to eat right. He reminds himself that there are other things in life besides music: family, friends, hobbies. He enjoys photography. When he gets stuck on a project, he takes a break. He tries to get out of his head. He reminds himself that, in order to have anything to say, he first has to live.

It is necessary to think this way, paradoxically, in order to work. Wire is already writing his next project. He wants the album to showcase his rapping and singing equally. He is working with some new producers. He has a title in mind, but has yet to announce a release date. He’s not in any rush. “I hope that I can get everything that I need out of my mind and my heart, [and] into the music,” Wire says. “I’m taking my time.”

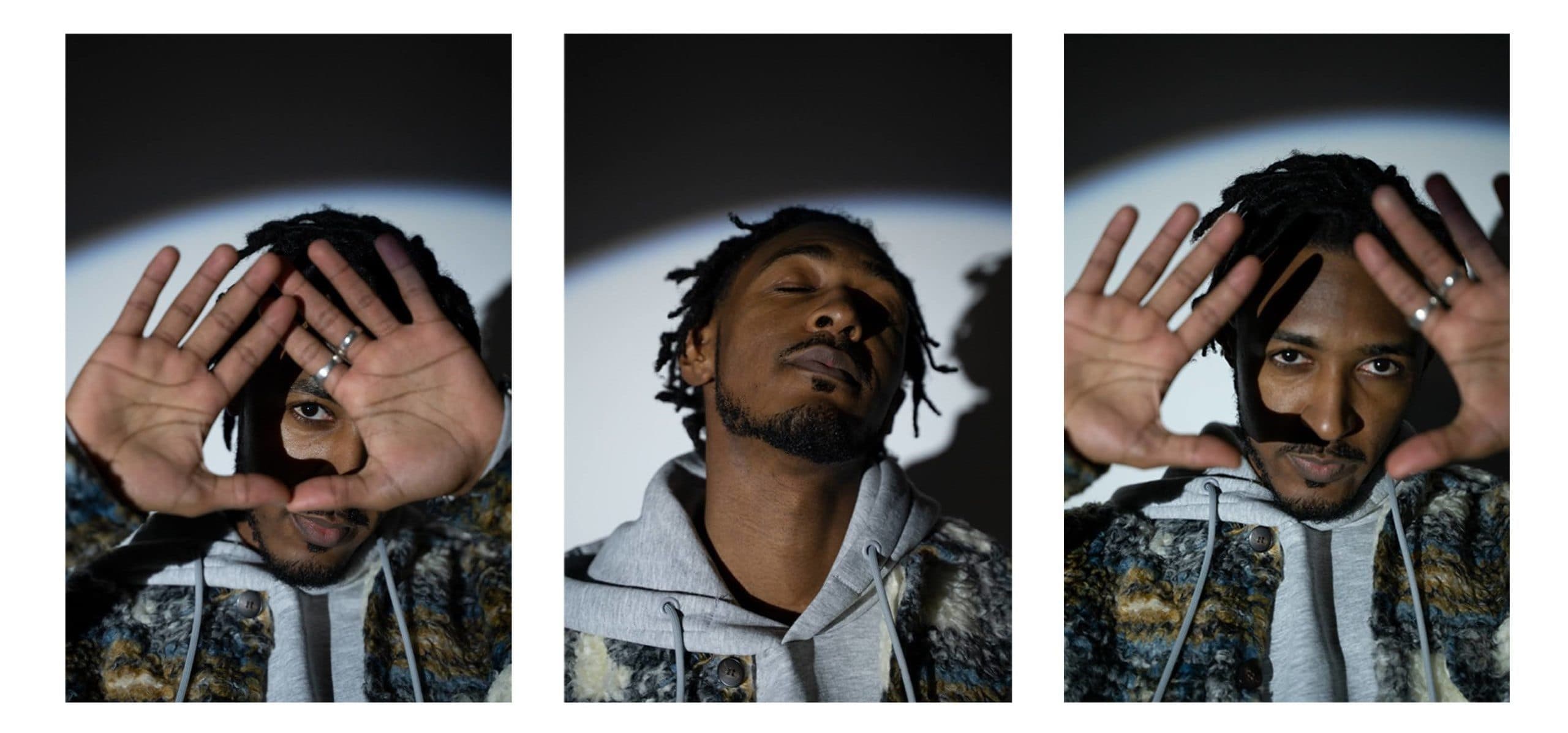

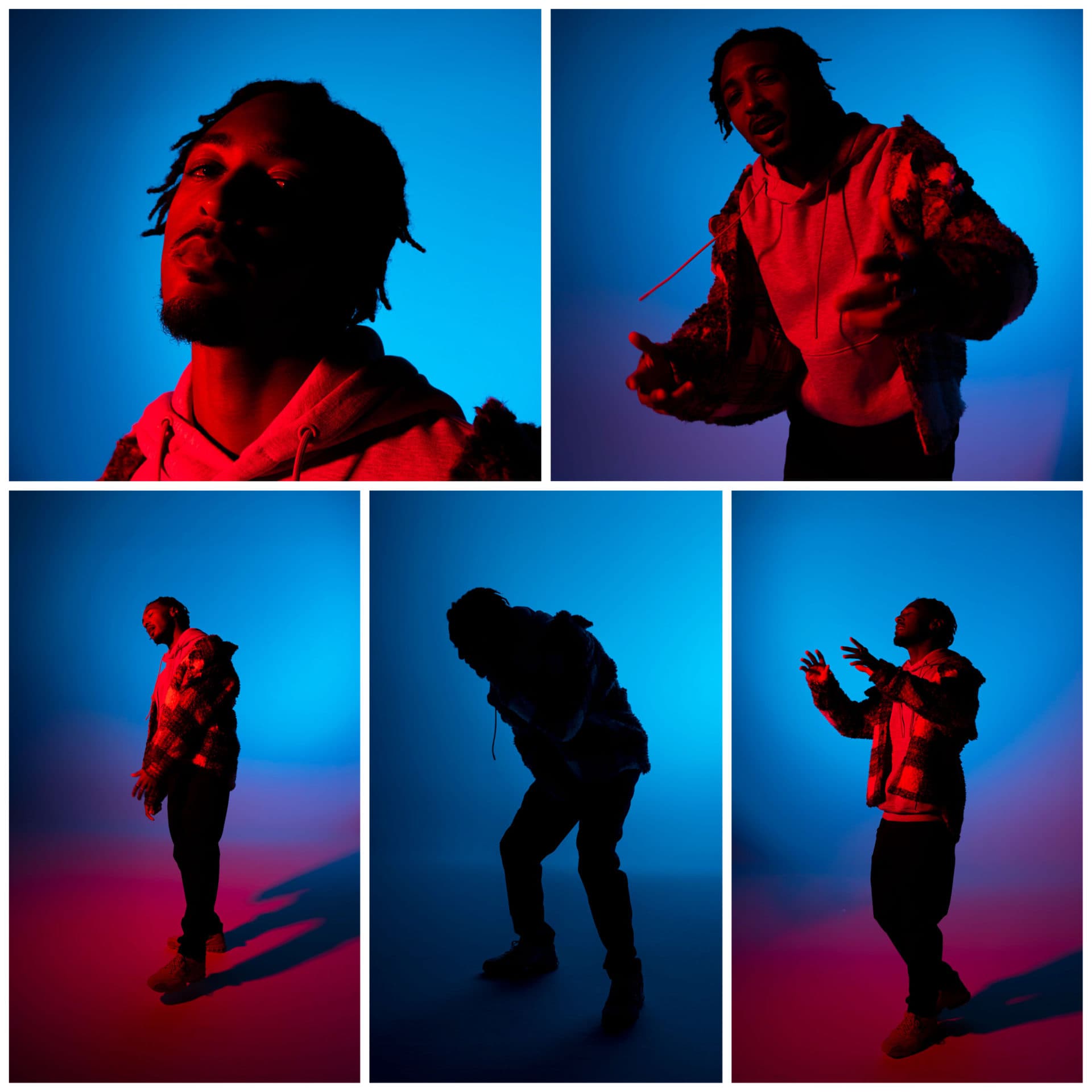

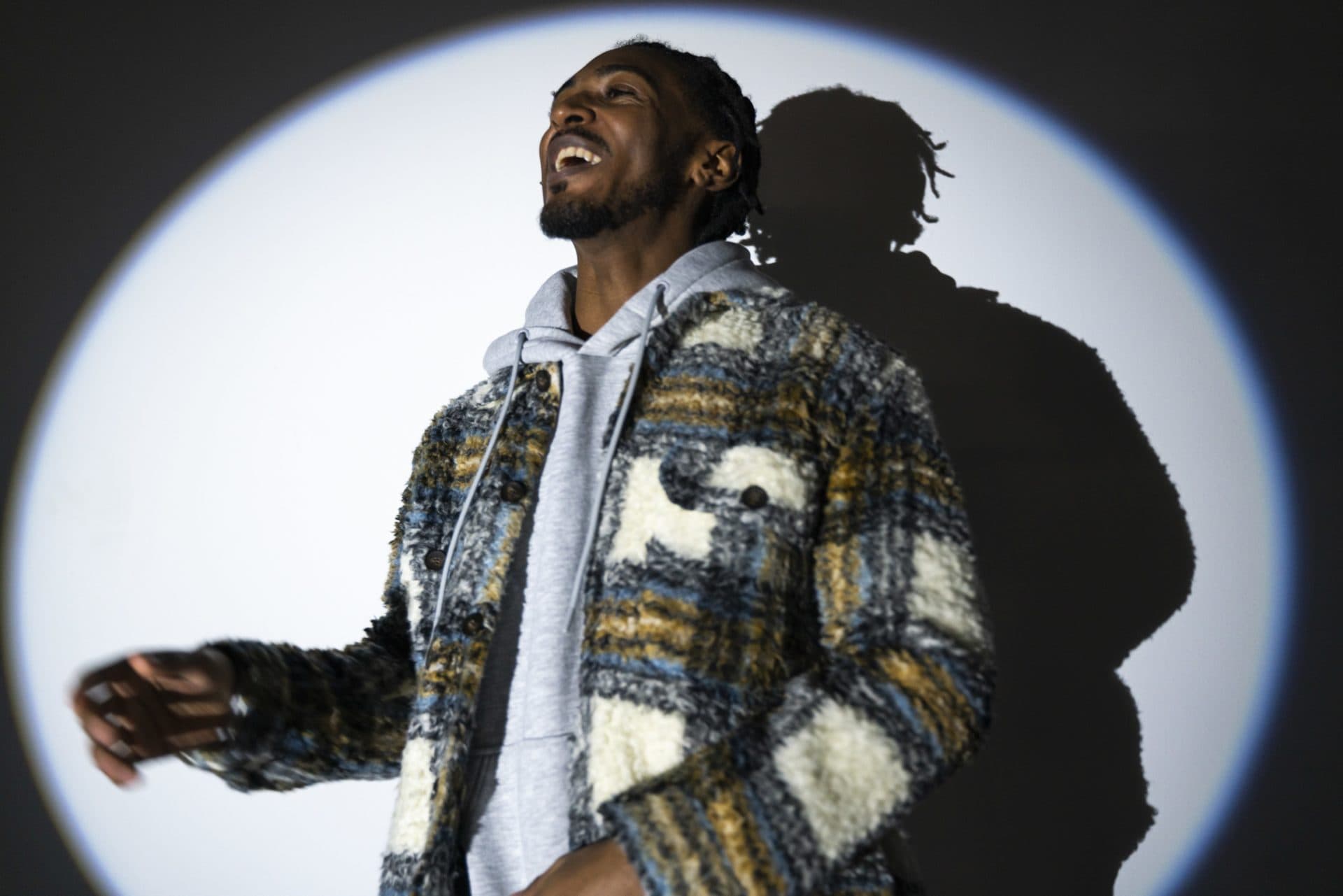

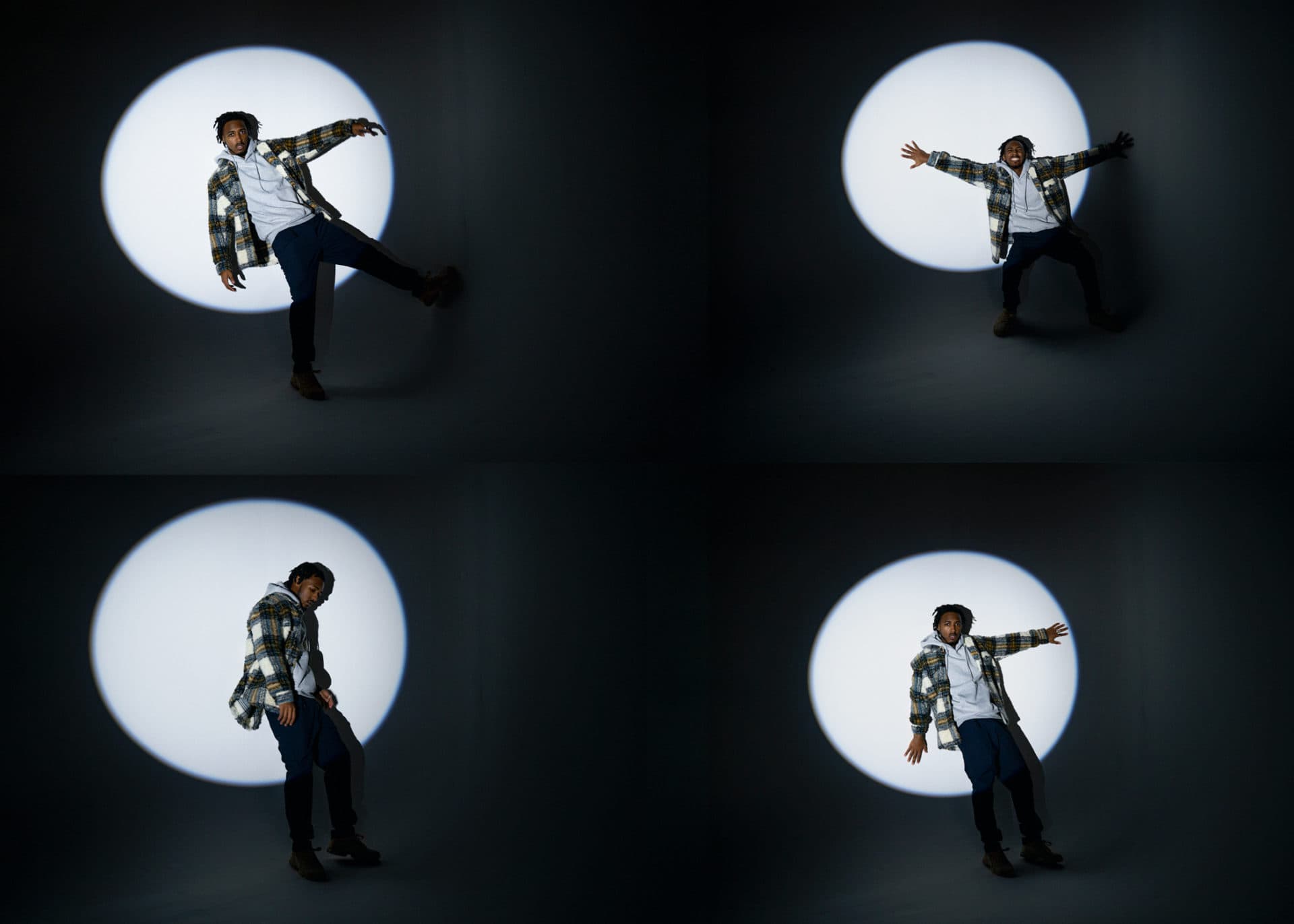

Here's a behind-the-scenes look at photographer OJ Slaughter's photo shoot with $ean Wire at Windy Films studio in Boston, filmed by WBUR's Robin Lubbock.

This segment aired on February 11, 2021.